Biden’s Zombie Broadband Plan

President Biden’s “American Jobs Plan” aspires to do great things for the American worker. Investing over two trillion dollars on infrastructure and social programs over a ten year period is bound to create a lot of jobs.

The plan says some good things about broadband and nuclear power, but it also displays a fairly disturbing lack of understanding of where these technologies stand. Promising to buy advanced nuclear reactors is great, but the Democratic Party has not fully moved beyond its anti-nuclear past to a full embrace of Small Modular Reactors and the breeder plants built in Russia, China, and India that consume their own waste.

The broadband portion of the Plan echoes the aspirational thinking of a prior age. It could easily have been written in the 20th century, when hard-wired networks were all the rage and wireless was little more than a far-off dream.

The Broadband Plan is Confused

More often than not, political treatment of the digital inclusion problem devolves into attempts to solve a social problem – poverty – with civil engineering. The Plan proposes to continue this error.

The Plan’s confusion is apparent in the way the fact sheet frames the inclusion problem:

[The Plan] will bring affordable, reliable, high-speed broadband to every American, including the more than 35 percent of rural Americans who lack access to broadband at minimally acceptable speeds.

The figure used to represent the number of rural residents who cannot connect to broadband at acceptable speeds – 35% – comes from a Pew FactTank post issued last May, Digital gap between rural and nonrural America persists.

What the Pew Fact Means

Pew’s 35% claim pertains to a different problem, the willingness or ability of rural consumers to pay for available services:

Roughly two-thirds of rural Americans (63%) say they have a broadband internet connection at home, up from about a third (35%) in 2007, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in early 2019. Rural Americans are now 12 percentage points less likely than Americans overall to have home broadband; in 2007, there was a 16-point gap between rural Americans (35%) and all U.S. adults (51%) on this question.

This doesn’t say a thing about available broadband speeds or whether people don’t have subscriptions because they can’t afford them, don’t want them, or just can’t get them. At least 71% of the rural Americans in the Pew survey have smartphones, tablets, or computers and they’re probably connecting them somehow.

Modest Fact-Checking

The Plan’s use of the “minimally acceptable speeds” trope suggests dissatisfaction with the data in this year’s Fourteenth Broadband Deployment Report by the FCC. Using the current definitions of fixed and mobile speeds, the FCC found that 82.7% of rural Americans have access to fixed (wired or wireless to one location) services at acceptable (25/3 Mbps) speed, and 90.8% have access to mobile service at 10/3.

Mobile Zoom will work well at 10/3, and simultaneous Zoom sessions will work at 25/3. So the president’s plan exaggerates the unserved rural problem by two to four times.

In the political context, doubling or quadrupling the size of a problem isn’t lying or misrepresentation, it’s ordinary puffery. But there is no technical justification for pumping up the definition of broadband to the arbitrarily unbalanced and high levels many in Washington propose.

Broadband Problem Poorly Conceptualized

The number doesn’t bother me as much as the likelihood that the president’s broadband experts don’t understand the difference between the problems that can be overcome by building networks from the ones that can’t. Exaggerating the inclusion gap to create a pretext for building new networks suggests a willingness to spend without investing.

Building networks for the hell of it with taxpayer money will create jobs in the short term without producing lasting benefits. In any case, the real numbers for rural broadband will look very different a year from now. The FCC data is also a year old, so not fully reflective of where we are today.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) broadband networks are coming online thanks (at least in part) to the Pai FCC’s willingness to subsidize Elon Musk’s Starlink network. That network – as well as similar offerings from three other providers – is in a beta test mode already, and early reports are quite rosy. Other rural networks using fixed location 4G and 5G LTE are also promising.

The Plan isn’t Stupid, it’s Just Aspirational

The fact that the president’s advisors have made a hash of the rural broadband problem doesn’t mean there isn’t one. Rural broadband is spotty and it is generally slower than urban offerings.

Government money can raise speeds and improve coverage. We see that in the year-over-year improvements apparent in the FCC’s Broadband Deployment Reports.

The White House plan has a not-very-well-hidden agenda. It explicitly favors government-owned networks over those built by the private sector:

It also prioritizes support for broadband networks owned, operated by, or affiliated with local governments, non-profits, and co-operatives—providers with less pressure to turn profits and with a commitment to serving entire communities.

This is nothing more than an appealing illusion.

Local Government is a Financier, not an Operator

There really isn’t a non-profit option for local broadband because municipal networks are generally operated by contractors or public/private partnerships. Profit margins for Internet service are not high, and the service is capital intensive.

There is a cottage industry of network designers and operators that feeds on small towns and rural counties. Consultants will happily design, install, and operate facilities that city staff can’t wrap their arms around. They will even help cities get federal grants to pay for their services.

Local government’s role is generally limited to writing checks and collecting bills. All the heavy lifting is done by specialist firms – the main promoters of government networks – who are very much in it for the money.

Out of Sync with Reality

One-time investments only go so far because networks require ongoing maintenance as weather takes its toll on infrastructure. Networks tend to be used more heavily over time, so ongoing upgrades to network capacity will also be necessary.

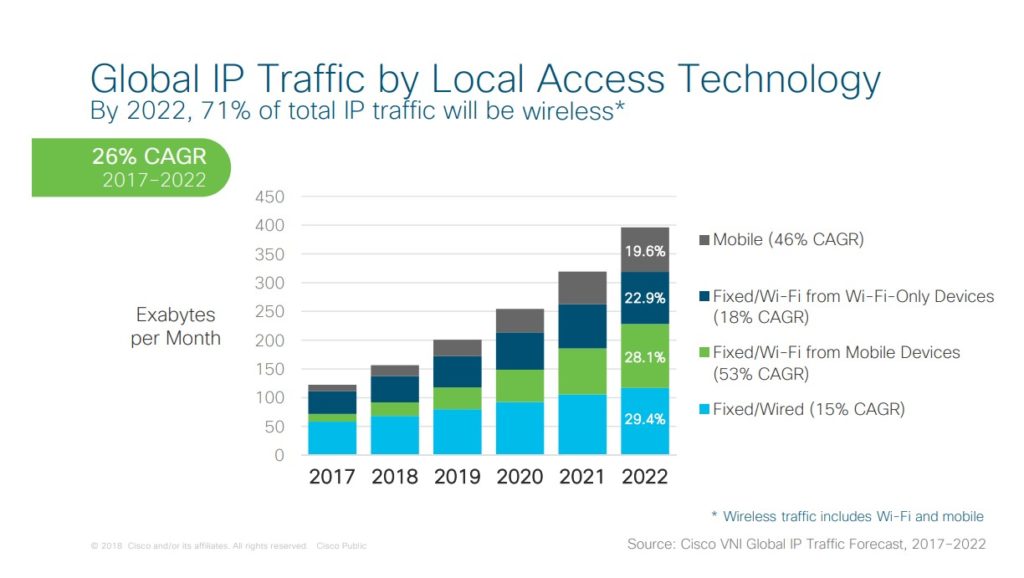

The Plan is already out of sync with consumer expectations because it emphasizes wired connections. By 2023, 71% of our Internet data will move over wireless facilities, and wireless is essential to rural America’s farm networks.

Internet Data is Mostly Wireless

The municipal broadband industry is working on upgrading its wireless game, but it isn’t nearly as good at 5G networks as the big players are. Most muni networks are obsolete by the time they’re built and better targeted at entertainment use than work, school, and farm management.

Magical Thinking about Subsidies

When the Plan mentions subsidies, it does so in an utterly fanciful way:

While the President recognizes that individual subsidies to cover internet costs may be needed in the short term, he believes continually providing subsidies to cover the cost of overpriced internet service is not the right long-term solution for consumers or taxpayers. Americans pay too much for the internet – much more than people in many other countries – and the President is committed to working with Congress to find a solution to reduce internet prices for all Americans, increase adoption in both rural and urban areas, hold providers accountable, and save taxpayer money.

This means nothing more than price controls. The claim that Americans pay far too much for Internet service is one of the staples of consumer advocacy in the broadband policy space, but it’s misguided and misinformed.

US Consumers are Not Overcharged

The claim that US consumers are overcharged comes from a relentless campaign on the part of the New America Foundation’s Cost of Connectivity series, but even that report admits that the cost of broadband is driven by usage, geography, and population density:

However, standardizing costs and speeds while also factoring in differences in population density reveals that U.S. providers on average advertise similar prices for similar speeds as European providers. For example, Washington, D.C. is almost on par with Zurich, with only a penny’s difference in average advertised costs per Mbps between the two comparably dense cities. Similarly, Bucharest, Copenhagen, and San Francisco all average advertised costs per Mbps within a five-cent range.

Not exactly a scandal, is it? See our podcast on the economics of broadband, and understand that subsidies for the poor are forever.

Solving America’s Broadband Problems

Twenty-five years ago, broadband was the central issue in US Internet policy. While policy wonks and the public once worried about unfair discrimination, monopoly firms, and gatekeeper power at the point of access to the Internet, we now know that these issues are endemic to the platforms erected by the giants of the day: Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft.

While cable and wired telephone services still dominate local broadband markets, genuine alternatives are emerging from fixed and mobile 5G service providers and LEO satellite networks. Consumers are wireless first and may soon become wireless only for Internet use.

We are truly at an inflection point in the history of communications technology. While we have work to do in rural and poor America, we are not at a point where we can afford to turn our backs on emerging technologies in favor of a zombie broadband plan born in the last millennium and reanimated for current political reasons.

We can do better.