Making the Internet Secure Once Again

The Internet has never really been secure, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have to keep raising the bar. This post will outline current developments that together represent significant progress toward protecting the browsing experience from certain kinds of snooping, hijacking, and observation.

One of these is a Wi-Fi enhancement known was Wi-Fi Protected Access version 3 (WPA3). WPA3 is good for all uses of Wi-Fi, even those that don’t leave the home or office.

Transport Layer Security version 1.3 (TLS 1.3) is end-to-end privacy for TCP. It’s both a security enhancement for transmissions across the whole Internet as well as a performance improvement.

DNS over TLS (DoT) is a privacy enhancement for Android DNS queries. Its purpose is to prevent ISPs from knowing which sites you’re visting.

DNS over HTTPS (DoH) is a follow-on to DoT that also shields DNS queries from ISPs. Like DoH, it’s intended to prevent ISPs from competing with the Internet advertising duopoly, Google and Facebook.

WPA3 Improves Public Network Security

Current Wi-Fi security is provided by WPA2, a shared key system. Its main purpose is authenticating devices when they connect to an access point or router, but it also provides rudimentary encryption.

When you set up a router, you assign a password to each of the two Wi-Fi frequency groups, and potentially one or two more if you set up guest mode. The trouble with this system is that all users of each frequency group share the same password.

Once you have the password and an appropriate snooping device, you can decode everybody else’s traffic. This is useful to hackers in coffee shop settings where the other users aren’t necessarily wary of snooping.

WPA3 assigns each device a magic number than prevents other users from decoding its transmissions. It also protects management frames that are vulnerable under WPA2 so hackers can’t force you to authenticate again. And most importantly, it protects networks from brute-force password hacking.

Slow Rollout

This means you don’t always have to use a VPN when you’re in a coffee shop, classroom, airport, or other public network. Some public networks will never implement WPA3, however. These are the ones where you enter a user name and shared password into a login form sent over an open network connection.

WPA3 will require the replacement of older routers and (at least) a firmware upgrade on newer ones. If you don’t share your WPA2 password with people you don’t trust, it won’t do anything for you apart from protecting you from brute-force attacks. This is useful, so I recommend getting it when it becomes available in 2019.

Currently, there are no WPA3-certified routers on the market. The Wi-Fi Alliance has certified a chipset – Qualcomm’s IPQ8065 – and routers will probably be available toward the end of the year. Click here to see certified devices.

TLS 1.3 is a Major Performance Upgrade

The first companies to adopt TLS 1.2 were Google and Facebook. It’s a big deal for them for anti-competitive reasons because it hides web content from ISPs.

It’s a headache for ordinary users because it imposes a lot of overhead on web visits. One of the main reasons that web pages take seven times longer to load than the time you would predict from page size and broadband speed is TLS overhead.

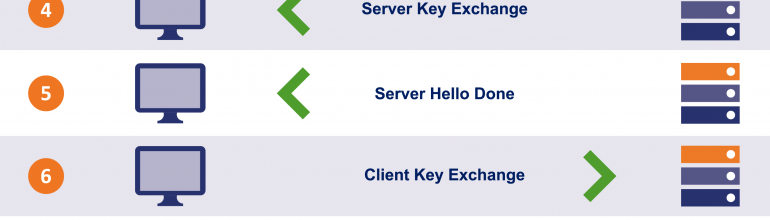

Web pages require about 30 TCP sessions to be created and torn down. Each TCP session that uses TLS 1.2 requires three handshakes to set up: the normal three-way TCP handshake and then two more TLS handshakes.

Handshakes are bad because their speed is disconnected from broadband speed. Whether you have a 10 Mbps plan or a gigabit plan, handshake times are governed by distance. Loading the typical web page today means you have to wait for nearly 100 round-trip circuits just for handshaking before you get any data.

While some people say TLS 1.3 improves Internet security – which it does – the major benefit to consumers is reduced overhead for hiding page contents from ISPs. You can see if your browser supports TLS 1.3 on this test page.

DoT is Dubious

DNS over TLS is a way of hiding DNS queries made to third party DNS – such as Google and Cloudflare – from ISPs. Without DoT, your ISP can know what sites you’re visiting. Google and Facebook would rather than ISPs don’t have this information because if they had it, they could monetize it by targeting preference-based ads to you. Standard DNS queries are plain text.

The ISP still knows what IP addresses you’re visiting, but in some cases a given IP address can host multiple web sites so the IP address isn’t an entirely useful identifier. Without plain text queries, home routers provided by ISPs will know next to nothing about your web habits.

DoT doesn’t do much for you unless you combine it with DNS Security Extensions, which you can only do by limiting your web surfing to domains that use DNSSEC. And there aren’t many of these.

DoH is Potentially Harmful

Most users don’t bother with setting up a third party DNS – we just use the one the ISP provides. DoH overrides this user choice by hard-wiring a browser to a DNS. In the case of Chrome, this will be Google’s DNS, and in the case of Firefox it will be Cloudflare’s DNS.

I can only assume that Cloudflare is paying Mozilla for the privilege of collecting your DNS queries from Firefox as the two companies have some sort of exclusive test agreement. When the feature graduates from test mode to production, I would be surprised if Mozilla doesn’t open the DNS up to other providers. The status quo is troubling, of course.

DoH raises all sorts of performance issues because of the way CDNs localize their servers. So once again, we see a feature touted as improving security when what it really does is simply share your browsing history with Google or Cloudflare instead of with your ISP. Whether that’s worth a performance hit is personal preference, but it’s not a feature that appeals to me. Google knows too much about what I do on the Internet as it is.

What’s Good Security and What Isn’t

WPA3 is a 100% beneficial security upgrade: it protects your Wi-Fi network from brute force password attacks and protects you from snooping on public Wi-Fi networks. As soon as it becomes available, I’ll start using it. TLS 1.3 is infinitely preferable to TLS 1.2 because it reduces the overhead inherent in visiting encrypted web sites. DoT and DoH are both very dubious.

It’s important to understand that once your Wi-Fi connection is secure, there’s no additional value to you from these other security measures. They don’t prevent Facebook and Google from tracking you all over the web and they don’t provide additional protection over WPA3.

It’s possible to disable TLS 1.3, but I wouldn’t recommend it. I have it turned on in both Safari and Firefox even though that’s a bit difficult at the moment. Unfortunately, nearly all encrypted websites are still using TLS 1.2.

Where We Go From Here

When DoH becomes standard in browsers, I intend to turn it off. It interferes with CDNs and does nothing for consumers unless they’re super-worried about ISPs having the same kind of information about their browsing habits that Google and Facebook have. And I don’t see much reason to share with Cloudflare at all.

An awful lot of things that are sold to us as improvements to Internet security simply deliver more information into the hands of a small group of companies. Whether that’s a good thing is for you to decide, but for my own part I like to be selective about what I share with which players.

Sharing a little bit with a handful of companies feels like a better deal than sharing everything with everyone or sharing everything with only one or two companies. The information is out there, and when used correctly sharing is beneficial.