FAA Proposes Token 5G Fix

Just when I want to publish a thoughtful post on the conflict between the aviation industry and the 5G C band rollout, the FAA goes and grabs the news cycle by grounding all flights in the US. Apparently the FAA’s ears are burning and the whole 5G thing embarrasses them.

Before damaging the NOTAM database yesterday, the FAA disclosed that the total cost of mitigating its perceived threat from the C band rollout is going to be $26 million. That covers 180 radio altimeter (radalt) replacements and 820 filter retrofits for a nice round total of 1,000 airplanes. Oh, flight manuals need to have a sentence added to them as well.

This revelation blew a lot of minds because the figure amounts to a rounding error on the $69 billion paid by Verizon and AT&T for the relevant C band licenses. All of the drama over threats of airplanes falling out of the sky was over an upgrade too cheap to measure.

Too Good to be True

But the story was too good to be true. Looking into the FAA’s proposed airworthiness directive in the Federal Register, eagle-eyed ITIF analyst Joe Kane discovered that the FAA is seeking to keep the current voluntary restrictions on 5G in the vicinity of airports in place:

BUT: new altimeters only have to be resilient against unwanted emissions up to -48 dBm/MHz, meaning they're only certified "as long as telecommunication companies transmit at parameters under the current voluntary agreements…" pic.twitter.com/laEnCHiyUl

— Joe Kane (@thejoekane) January 9, 2023

This token mitigation measure obviously doesn’t solve the problem. In fact, it’s just more “airplane mode” for commercial aviation as I described in my recent op-ed.

Actually Solving the Problem Needs More Work

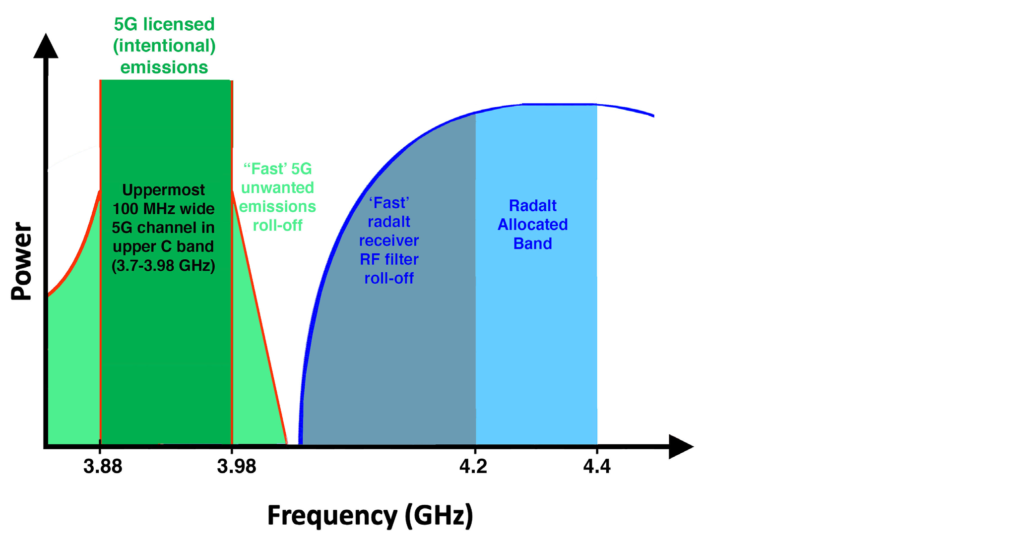

5G providers hold licenses purchased at auction for a spectrum band ranging from 3.7 to 3.98 GHz. Aviation is entitled to use a band ranging from 4.2 to 4.4 GHz globally. Aviation complains that 5G base stations interfere with its airborne radalts.

A comprehensive study conducted by the NTIA’s Institute for Telecommunications Sciences at its Boulder County “Table Mountain Radio Quiet Zone” measured the power emitted from 5G base stations. This exercise is part of a larger program to study radalt/5G compatibility for both the commercial and military sectors.

ITS observes that interference harmful to aviation can only exist in two scenarios: either 5G transmits significant power outside its assigned frequency or radalts listen for power outside its assigned frequency. Given that the two bands are separated by 200 MHz, it should not be hard for both systems to operate without interference, as this diagram from the report illustrates:

Figure 27. Ideal spectrum filtering and roll-off for avoiding both potential interference mechanisms between adjacent-band 5G transmitters and radalt receivers. Source: “Measurements of 5G New Radio Spectral and Spatial Power Emissions for Radar Altimeter Interference Analysis”, NTIA Report 22-562, p. 51.

Reality is a Bit More Complicated

Even in the ideal scenario, we can see some energy escaping from the 5G licensed band into the unoccupied buffer zone between 4 and 4.2 GHz. With a sufficiently sensitive receiver, some of this energy will be detectable above 4.2.

A sufficiently sensitive receiver can, in fact, detect energy in the radalt band as well as in bands well below and well above the radalt band. This is why both transmitters and receivers both need to behave well in order for coexistence to occur. Advocates who say coexistence is all on the receiver are only telling half of the story.

The regulatory question is how much out-of-band (OOB) energy receivers need to tolerate. The answer to this question also tells us how much OOB energy transmitters are allowed to generate. Zero is not the answer because sources of RF energy are everywhere; the sun is one of them.

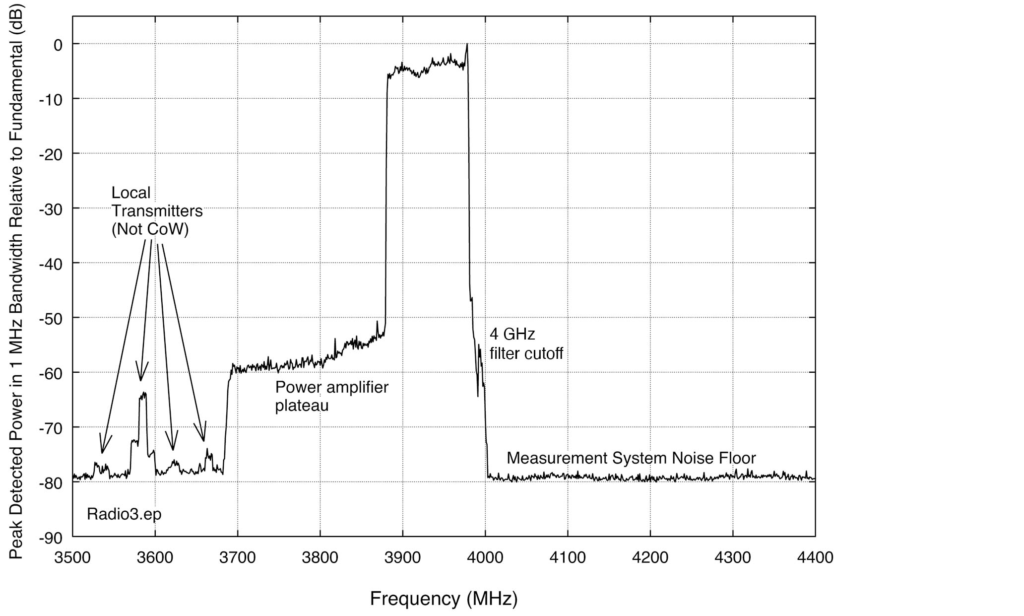

The Table Mountain measurement system did find some OOB emissions from 5G base stations, but it didn’t reach the boundaries of the authorized radalt band. Here is a representative measurement.

Figure 47. Measured emission spectrum of 5G base station transmitter Radio 3. Source: “Measurements of 5G New Radio Spectral and Spatial Power Emissions for Radar Altimeter Interference Analysis”, NTIA Report 22-562, p. 89.

Note: “Measurement System Noise Floor” is energy detected when the base station was turned off.

Is There a Problem?

ITS says very clearly that it did not find any 5G energy in the radalt band:

Across the frequency range of 4200–4400 MHz, we never saw any perceptible power from 5G emissions in the 100 ms time domain scans at each frequency step. We could visually see an impact of as little as 1/10 of a decibel above the analyzer’s noise. If such an emission had been present, we would have seen the very distinct TDD ON/OFF cycling every 5 ms. In effect, we would have seen “ripples” every 5 ms which would have been the “tops” of the TDD cycles shown in Figure 15.

In fact, ITS determined that 5G energy would have been at least 15 dB below its measurement noise floor. If radalts are unable to function when 5G is active that can only be the fault of radalts listening into the 5G licensed band itself.

Yet FAA wants to keep voluntary transmission limits in place for the 5G band. This insistence implies that the filters currently used on radalts are not filtering out distantly adjacent signals.

Too Late for Half Measures

FAA is one of the participants in the Joint Interagency Fifth Generation (5G) Radar Altimeter Interference (JI-FRAI) Quick Reaction Test (QRT) task force that directed the ITS measurements at Table Mountain, as are several aviation industry manufacturers and trade groups. Surely the agency is aware that the parameters it proposes in the NPRM for the proposed AD are irrational.

The FCC has proposed performance limits on receivers adjacent to the upper C band. Unless FAA is looking for yet another temporary variance, its AD should follow the FCC’s lead. If aviation can’t meet these limits – even after replacing the worst 180 radalts and filtering 820 others – it has some explaining to do.

Absent exigent circumstances (supply chain disruptions and the like) a single cycle of radalt upgrades and add-on filters should be sufficient to ensure compatibility with 5G. If the current replacement cycle needs to be followed by another to ensure both air safety and full compatibility, we need to know why.

Perhaps this would all be easier if FAA had an actual professional administrator approved by the Senate. But that’s an issue for another post.