Europe’s Broadband Woes

By any sensible measure, Europe is in the midst of a broadband crisis:

- The U. S. has opened a an enormous gap with the continent in terms of 4G/LTE mobile broadband, which is now available to over 90% of the nation from two carriers with two more to follow, while only a quarter of Europeans have any access to it at all.

- Mobile phones and mobile phone platforms are mainly made by American firms and Asian ones who license Android from Google.

- No global Internet services of any note are hosted by European firms except The Pirate Bay, a piracy site that mainly gives away American music, TV shows, and movies. Of the top 15 web sites in the world, 12 are owned by American firms (and the other three are Chinese.)

- Americans have greater access to the fastest wired broadband, fiber and cable: 20% of American homes can subscribe to fiber to the premise broadband if they want, and more than 95% can subscribe to cable broadband. In Europe, fiber reaches only 15% of homes and cable 50%.

- On top of all that, American telecom firms invested $50.5B in 2012, largely on facilities upgrades.

The upshot of that is that 95% of America’s young adults, those aged 19-30, use broadband services at home, by either wire or mobile, and virtually 100% of those aged 19-25 are broadband users.

This leads directly the scenario where Internet services are concentrated in the U. S., as they clearly are according to the Alexa rankings of the top web sites:

- YouTube

- Yahoo!

- Baidu.com

- Wikipedia

- QQ.COM

- Windows Live

- Amazon.com

- Blogspot.com

- Taobao.com

- Google India

- WordPress.com

Is it at all likely that 12 of the top 15 web sites would be owned by U. S. firms if our broadband networks were under-powered, overpriced, or confined to gated communities (as some critics charge)? Our networks are part of an ecosystem in which innovation in devices drives the creation of services and in which networks are continually upgraded to meet application demands. We don’t strive for Soviet benchmarks, we strive for customer satisfaction and and market leadership. The dynamic character of this ecosystem is the portion that the central planners always miss.

These are the crucial ingredients of the pervasive computing and communications economy, and they’re all here: networks, systems, and applications.

Europe’s leading communication policy-makers know they have a problem. Neelie Kroes has been beating the drum for the past year for massive public investment in broadband infrastructure and for harmonized markets and regulations to break down the barriers that regulation and policy have erected against innovation in Europe. She has not been successful, as the budget is simply not there for the kind of catch-up spending that Europe needs, but there’s no doubt among Europe’s policy makers that the U. S. is ahead:

Kroes told Reuters in June that she supports consolidation as a way to create a handful of strong cross-border operators which can invest more in mobile and broadband networks to close the gap with the United States and Asia.

In light of these facts, it’s peculiar that a few American analysts, journalists, and advocates continue to make the false claim that the U. S. is falling behind. Washington Post blogger Timothy B. Lee claims “We’re falling behind on residential broadband” and fellow blogger/reporter Brian Fung wants the U. S. to learn “What Europe can teach us about keeping the Internet open and free” by following Europe’s regulatory model.

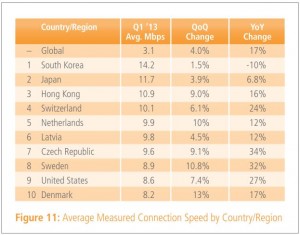

These bloggers are factually challenged. The U. S. is not falling behind Europe in residential broadband, we’re pulling ahead. Akamai ranked the U. S. 22nd worldwide in broadband speed in 2009, but they rank us 9th today, behind 5 European and 3 Asian nations (counting Hong Kong as a nation.) There are 27 nations in the European Union, so the arithmetic says our networks are faster than those in 22 nations, including all the largest ones (Germany, France, UK, Italy, Spain, etc.) and pulling ahead.

Source: Akamai State of the Internet Report, Q1 2013.

Lee bases his judgment solely on the fact that Verizon has announced that it has stopped deploying FiOS, a fact that means much less than he thinks. For one thing, Verizon hasn’t actually stopped deploying FiOS: they recently announced that Western Fire Island will get it, and they’re also replacing failed copper wire with fiber in New York City and elsewhere.

The United State is also continuing to install new fiber at a faster rate then Europe is (source: CRU Group, “CRU Monitor: Optical Fibre and Fibre Optic Cable”, September 2012), and much of it is going into the mobile and fixed broadband markets. AT&T and Century Link are installing fiber in residential networks that bring high speed VDSL and Vectored DSL to homes at speeds of up to 50 Mbps and 100 Mbps respectively. High speed, part fiber DSL services are gaining subscribers faster than cable is.

Leaving fiber aside, the U. S. offers cable Internet service to twice as many homes per capita as Europe does; we’re awash in fiber, cable, and 4G/LTE while Europe struggles to get by with DSL and 3G. To top it off, American broadband users get 96% of advertised speeds, while Europeans only get 74%. The reality couldn’t be more obvious: this is not what “the US is falling behind” looks like.

So the question that has to be addressed is why these bloggers for a major U. S. daily newspaper can’t manage to get the basic facts straight. It looks like they’re not even trying.

Lee says “neither side of the broadband debate wants to admit” that the U. S. is falling behind. Maybe that’s because we aren’t.