The Growing Demand for Spectrum

I’ve written a column for CNET on spectrum policy, “Meeting the need for spectrum,” addressing some of the arguments we hear about spectrum demand and supply. Some advocates insist that the demands of mobile broadband users for increased data capacity can be met without allocating the additional spectrum recommended by the National Broadband Plan, but that’s not realistic. While it’s certainly true that spectral efficiency has steadily increased for the past 100 years, the rate at which it increases is considerably slower than the rate at which demand is currently increasing. The rule for spectrum is “Cooper’s Law,” which stipulates a doubling of efficiency every 30 months. Contrast that with Moore’s Law forecasting a doubling of semiconductor capacity every 18 months and you see part of the problem. Factor in the demand growth that comes about as people trade in dumb phones for smart ones and you see the problem in full.

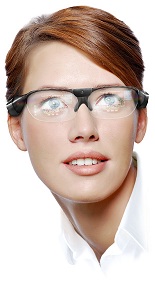

Source: Laster Technologies

In the fairly near future, smart, mobile devices will become ubiquitous, and we won’t even recognize them as phones. Cars will become rolling mobile networks, and we’ll have smart mobile devices embedded in our eyeglasses and clothing. Consider the IEEE Spectrum’s Technology of the Year for 2011, Laster Technologies Smart Spectacles.

This is a wearable computer that projects images directly to the eye and captures images through a video camera on the nose piece, powered by a smartphone with Bluetooth. In years to come, products like this one will integrate the smartphone and function as standalone devices. You could be looking at the iPhone 10 circa 2020, a device distributed by optometrists.

In the face of the demand growth that such devices will bring about, it’s prudent to pursue every avenue that makes more capacity available to the user: Efficiency, construction, advanced technology, and spectrum, but there’s no substitute for spectrum.

Check out the CNET column at: http://news.cnet.com/8301-1035_3-20062663-94.html

We’re going to have a panel discussion of these issues on Capitol Hill this Tuesday at noon, featuring High Tech Forum contributor Steve Crowley and additional luminaries. The event information is here: http://itif.org/events/waves-innovation-spectrum-allocation-age-mobile-internet.

Older radio technology has a lot of room to improve in terms of efficiency, but I’m not sure if the same rate of improvement applies to modern mobile data networks.

Some spectrum efficiency is gained through spectrum reuse but that is limited by how many cell towers the carriers can build. The limit is based on economics and local governments against new towers.

Some efficiency is gained through better radio modulation but that is limited. Shannon’s law gives us the absolute theoretical limit but the practical limit is far lower when we have to operate at much lower signal level due to longer ranges and obstacles like walls of a home and cars. LTE uses a lot of the same modulation techniques as the newer HSPA standards but in practice, the most aggressive modulation can’t be used and we’re stuck at the lower speeds per MHz at a given signal level.

MIMO can bypass Shannon’s law to a degree but it requires multiple radios on the transmit and receive end. The additional radios add cost to the radio equipment on both ends and I wouldn’t be surprised if there is a practical limit to the number of spatial streams that can be supported on a frequency.

At the end of the day, spectrum is the one raw material that really helps to expand capacity. Spectrum is ultimately limited as well but so long as spectrum is being wasted, we should reassign that spectrum to more efficient technologies.

NAB says broadcasters are more efficient, because they send more bits/sec/Hz.

Steve, NAB’s comparison is invalid because TV requires an external rooftop antenna the size of a small tree branch. We don’t require people to carry cell phones with branch size antennas and to sit on the rooftop while calling. People make calls with 4 inch antennas in locations that block 90% of the signal due to the walls of cars and homes and then the user blocks another 90% with their hands.

Furthermore, the cell networks don’t waste 2/3 of their spectrum with 40 thousand square miles of white space needed per full strength TV tower. The amount of spectrum reuse implemented by cellular carriers vastly exceeds that of the TV broadcasters.

I also want to add that the point isn’t who broadcasts more bits per second per Hz because these are two vastly different applications with different engineering requirements. The point is that there is in fact a lot of waste with TV broadcasting and that there are better technologies for accomplishing the same thing while using far fewer MHz for TV.

I agree. I made some of the same points in my piece on the recent NAB and CTIA reports, in which I called it an apples and oranges comparision, but it remains a tenacious talking point. One advantage broadcasting has is the number of simultaneous users that can be served. Cellular is limited by interference or MAC address limitations to, as one example, 400 VoIP users per sector for LTE. Broadcasting can serve an unlimited number of users. Thus, for one-to-many wireless distribution, it is efficient.

By “MAC address” I mean a unique identifier in the air interface, not an IEEE 802 MAC address. That’s not an issue with the newest air interfaces.

Again, user capacity per sector is irrelevant since it’s a completely different application and comparing different coverage area.

There are far more mobile users per MHz of (auctioned) spectrum than there are TV viewers per MHz of freely allocated TV spectrum. There is far less investment and far more waste in TV broadcast technology compared to mobile technology.

That’s my point. Its a different application. On the less investment point, they’ll say that’s a feature. You can tell them they “waste” spectrum, but they’ll say they do not.

150 mile radius guard band for a full power TV tower is waste regardless of what the NAB claims. No objective engineer would look at that situation and call it anything other than inefficient or wasteful.

Inefficient or wasteful along which dimensions?

When more than 2/3 of a 300 mile wide coverage area can’t use a 6 MHz band, that is grossly wasteful.

That’s a good point. At least a couple sets of measurements show some government bands have less occupancy than the TV band. Also, the white space industry will increasingly use some of the space between the TV channels to provide rural broadband, something it isn’t permitted to do on government frequencies.

The “but government is even more wasteful” argument isn’t particularly persuasive in front of a government agency. When it comes time to reclaim wasted spectrum, the government will look at broadcast TV waste first, especially when it’s sitting on such good frequencies.

As for rural broadband, white space frequency are generally allocated around 2-3 6 MHz channels which is peanuts within 222 MHz of UHF spectrum. The much bigger cost for rural broadband is building out physical infrastructure and not the cost of bidding on spectrum. Furthermore, the part 15 unlicensed aspect of white space devices is dubious for rural broadband especially when anyone can use those channels any way they like. If someone wants to use up all the available channels to video monitor their farm animals even if that interferes with the broadband service, nothing can be done because these are unlicensed bands. It might be all clear now because there aren’t many white space devices yet, but just wait.

Under the Communications Act, the President assigns frequencies to government stations. No persuasion of government agencies is required.

Rural WISPs use Part 15 now and are getting interference in the 2.5 GHz Wi-Fi band, because of the phenomenon you cite. White space technology brings new, interference-free capacity that propagates further over irregular terrain compared with microwave frequencies. All white space devices have to either include geolocation capability and be able to access a TV white spaces database, or communicate with a master device. Video monitors and other, traditional, Part 15 devices are thus not good candidates for the white spaces. Interference could still grow over time, but perhaps not so fast.

As the White Space concept matures, systems will need to be developed to resolve conflicts over access rights in locations where congestion and overload emerge. The data base provides a lever from which these policies can be enforced, fortunately. One might expect that white space congestion will rise very quickly owing to the increased propagation, which permits a given transmitter the ability to reach receivers who are very far away.

Steve, how are White Space devices “interference-free” from other White Space devices. The larger propagation characteristics of White Space frequencies will mean that there will be more interference from other unlicensed White Space devices.

WS frequencies are currently “interference free” because they’re unused.

Both of you are right. I use “interference-free” in a pragmatic sense. The areas most in need of rural broadband service have the most channels available for use under the white space rules. If you’re a WISP in, say, Laramie, Wyoming, there are 25 white space channels available — 150 MHz total. Yes, the channels you pick to provide service could get interference, but chances are another provider would pick other channels. Longer term the WISPs would prefer licensed spectrum. An appropriate market mechanism should make that available at reasonable cost in Laramie.

That would clearly be Brett (Google-hater) Glass’ preference: Exclusive use of a nice big chunk of spectrum without paying for the privilege.

[…] [Cross-posted at High Tech Forum] […]