Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Privacy

I had the pleasure of taking part in a panel discussion about privacy in general and the FCC’s privacy NPRM in particular today. The event was sponsored by Cal Innovates at the Senate Russell Office Building with a stellar cast: the keynote was given by former FTC chairman Jon Leibovitz, moderation was ably handled by Fawn Johnson of Daily Consult, and the panelists included Harold Feld of Public Knowledge fame and Tim Sparapini of Cal Innovates in addition to yours truly. You can stream the video here thanks to the Internet Society, who recorded it.

Leibovitz’s Keynote

Leibovitz delivered a very comprehensive picture of the statutory powers, process, and history of the FTC with respect to privacy. On one of the burning questions of the day, he opined that he’d rather see the FTC take jurisdiction over Internet Service Providers, but that can’t happen without amendments to the FTC Act and probably the Communications Act as well.

Perspectives

Harold accused the ISPs of wailing and gnashing their teeth over the regulations the FCC proposes to impose upon them because, in his view, the NPRM is perfectly lawful, consistent with American values, and consistent the way privacy has traditionally been regulated in our country.

Tim, however, pointed out that our current privacy regime is a colossal mess, the conclusion that is easily drawn from the facts Harold cited: the FTC is the principal privacy regulator, but privacy isn’t its sole, or even main, duty. There are multiple exemptions from FTC jurisdiction, such as the common carrier exception, the medical exception (HIPAA), banking exceptions, and even meat packer exceptions.

Companies have Multiple Roles

And in many cases modern technology firms are in multiple markets with multiple services which fall under different agencies with different privacy expectations. Hence, the US needs a rewrite of its privacy laws to resolve the complexities and inconsistencies between the different regimes. Just about every company is in the data business today, regardless of any analog goods or services they may sell.

Harold is perfectly comfortable with the status quo as he sees some sort of marvelous pattern in the interactions between the agencies. The pattern is a bit less fantastic to the firms subject to common carrier regulation who both cooperate and compete with more lightly regulated rivals, of course.

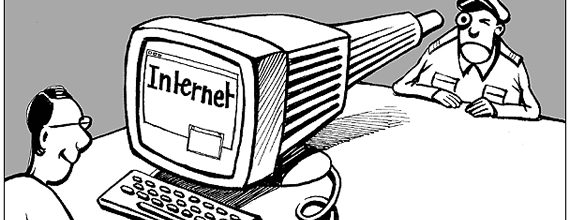

My Concern is Innovation

I made the argument for innovation, stressing the benefits that Americans reap from the data generated by our activities, devices, and patterns of life. We’re living longer and better than ever before, and that comes down to advances in science and technology developed by entrepreneurial firms guided by our mainly free market system. The science and tech part depends utterly on having data that can be processed and analyzed to heighten insights about food, medicine, social life, and personal growth.

The web depends on advertising for its financing, but it’s fast approaching a crisis where it becomes so bloated with poorly targeted advertising that it becomes too annoying to use. People are withdrawing from participation in the open web – the blogs and smallish web sites that used to be its main draw – and are cocooning in social networks. That retreat, along with the declining quality of web search, means the Internet is veering away from open access to information to closed systems that resemble pre-Internet communities such as AOL.

Artificial Distinction

The common carrier exception in the FTC Act delegates regulation of some communication networks to the FCC. The FCC’s reclassification of ISPs as common carriers puts them under FCC jurisdiction in terms of privacy, hence the FCC’s privacy NPRM and the attendant battle over the specifics of FCC regulation.

As I argued at the time the FCC was going the common carrier way, the distinction between firms that offer networking as a service and those that offer communication as a service barely makes any sense on its face, let alone in its details. ISPS such as AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, and Charter connect us with the rest of the Internet, but so does Google. ISPs connect us to each other, as does Facebook. Google and Facebook (and Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, et al.) offer services based on their own networks, data centers, software, and data, and so do ISPs.

When you comment on a friend’s status on Facebook, your ISP takes you to the Facebook network, which transmits your comment to your friend’s ISP’s network. So it’s multiple networks from end to end, and the ISP network isn’t even the one that does the most work.

Conclusion

Regardless of the current structure of US privacy law – the mess – the FCC could do a better job with its privacy rulemaking. The NPRM takes off from faulty premises with respect the sensitivity of data harvested by ISPs and the steps that can reduce risks to consumers from this information falling into the wrong hands. The NPRM presumes, incorrectly, that aggregation is the only meaningful form of de-identification. This is provably wrong according to real world trials conducted by Khaled El Emam of Privacy Analytics, the results of which have been presented to the FCC.

I’ll have more to say about de-identification later, but for know it’s best to think of it as a form of encryption.