High Tech Carolina Farm to Switch ISPs

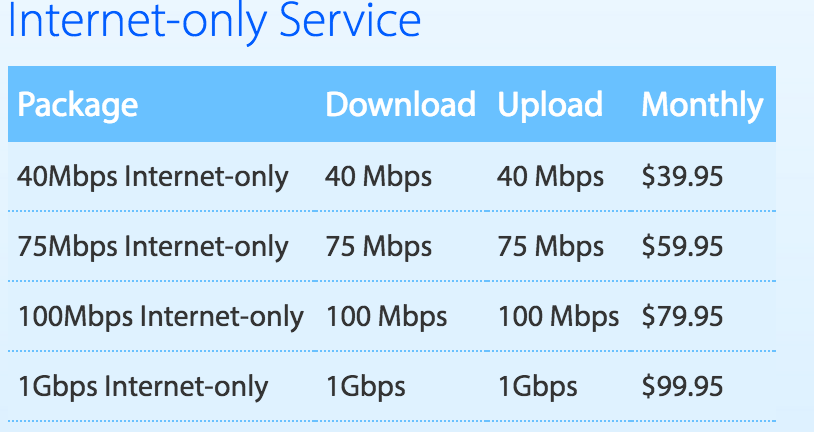

Vick Family Farms, located just outside Wilson, North Carolina, produces a typical Carolina crop mix of tobacco, cotton and sweet potatoes with “controlled atmosphere” storage. The farm currently uses a broadband service provided by Greenlight, the municipal broadband service in Wilson. This service is illegal under North Carolina law, so the farm will be changing ISPs now that the federal courts have clarified the law. While Greenlight offers speeds up to 1 gigabit/second, it also offers packages as slow as 40 Mbps; it’s unclear which service level Vick needs

North Carolina Law

North Carolina law prohibits municipal broadband departments from providing service outside the city limits, but Greenlight serves the one square mile town of Pinetops anyway. Greenlight extended service to Pinetops because the FCC issued an order authorizing it to ignore the law. It turns out the FCC’s order is unlawful, so Vick may need a new ISP. Their old one, CenturyLink, can provide 20 Mbps download speed, but the Vick operation will work better with faster upstream connection than CenturyLink’s DSL can provide.

Cecilia Kang’s article in the Monday New York Times, Broadband Law Could Force Rural Residents Off Information Superhighway, suggests the Vick farm is in jeopardy because it will no longer be able to get the kind of broadband connection it needs, but I’m not so sure the story is 100% accurate. [Note: oddly, Kang’s story doesn’t mention the fact that tobacco is Vick’s number one crop.]

Vick Farm’s Options

It seems to me the Vicks have a number of options:

- Wilson can annex Pinetops and make the existing service lawful. Pinetops is a very small town consisting of 600 houses in one square mile that probably gets its electric service from Wilson already, given that the larger town provides electricity to five counties.

- If Wilson chooses not to annex, it will have to sell the broadband network it built for these 600 homes, and it’s not unlikely that a regular ISP – maybe even CenturyLink – will buy it. Google may be another option, as it loves to acquire muni networks at firesale prices.

- If CenturyLink’s upstream capacity isn’t good enough on a single line, the farm can buy two DSL lines and bond them.

- There may be an rural LTE option available that runs at the required speeds.

In any case, it’s rather unlikely that the Vick farm is in the same shape as an Atlantic City casino even though it has been doing a bit of gambling.

Fiber-to-the-Farm Cautions

I’d like to see the farm succeed, even if I don’t necessarily approve of tobacco growers. There’s nothing wrong with cotton and sweet potatoes, and in the fullness of time the Vicks can probably transition from tobacco to soybeans as most of their neighbors have. Soybeans don’t need the state of the art curing that tobacco does, so switching to more socially acceptable crops may relieve some of the broadband capacity issue as well. Cotton and sweet potatoes are both transgenic crops (sweet potatoes naturally), so the farm is high tech from seed to market.

But annexation seems like the easiest route. It fully complies with the law and recognizes the fact that Pinetops is effectively a part of Wilson.

That being said, it strikes me that North Carolina broadband law could do with some tweaking. The Tennessee law that the FCC also tried to vacate doesn’t make the Pinetops situation problematic. Electric utilities in Tennessee are allowed to provide broadband service across their entire footprint, not just inside the city limits. Since Wilson provides electric service to Pinetops, broadband could be tacked on with the boundaries. This law is intended to protect the ratepayers who finance broadband expansions that extend service to non-ratepayers, which seems sensible enough.

But NC law is written the way it is because some cities have gotten ahead of themselves in the past and used electric service fees to build networks for which there was insufficient demand to cover costs:

In part, the rationale for these measure is complaints the lawmakers have heard from residents of Davidson and Mooresville, the North Carolina towns who bought the Adelphia cable system out of bankruptcy by forcing the issue in court (Time Warner Cable wanted to buy it as well) and have run up some impressive losses since the purchase: They committed $92M in bonds, and have lost $6.1M on operations since 2009.

So it’s not entirely correct that the NC law was simply written by fat cat lobbyists who snookered rural simpletons.

Colorado Broadband

It seems to me that Colorado has struck a reasonable balance in requiring a local ballot initiative before a municipal broadband project can go forward. Not all of these initiatives succeed at the ballot box, but many do. This step ensures that the town’s voters are motivated to use the service when the network is built, which has the effect of limiting the number of Davidson/Mooresville projects. So the ballot mirrors Google’s approach to gauging willingness to subscribe before putting shovels in the ground.

It’s also unclear how well the muni networks work in real life, but that’s an evolving story. It is clear that muni networks are good for the private contractors who generally build and run them. They also seem to be most common in areas served only by CenturyLink DSL without a cable option. That’s not always the case, but it’s a common pattern.

Fighting the Future

If I were in a community that’s contemplating a government broadband buildout, I’d want to know what the prospects are for improvement in the existing network. It’s often the case that the existing network will improve over the span of time in which a new network is built and debugged by the power company. Many rural communities are expensive to serve because they’re sparsely populated, and in that scenario one network is better than two. Upgrade dollars go farther than competing-for-eyeball dollars.

And there are also technology progress issues. It seems reasonably clear that the action for residential and agricultural broadband is mainly in the wireless space, with fiber backhaul playing a smaller but still significant role. Just as nobody wants their child to be last soldier to die in an unwinnable war, nobody wants to pay for the last wired network in their community. Pinetops is looking for better broadband, like much of rural America, but its real needs are rather modest.