Happy Birthday, Internet: Richard Bennett talks with Don Nielson

Since, Saturday August 27th, is the 40th anniversary of the first transmission over the Internet, Richard spoke with Don Nielson, the man who made it happen. Don explains the successful test his team conducted with a mobile digital radio truck parked outside Rossotti’s beer garden in Portola Valley, California, and the ARPA office in Boston.

So the team equipped a delivery van with a DEC LSI-11 minicomputer, two packet radios, and an antenna and ran a cable to a picnic table inside Rossotti’s where Nicki Geannacopulos was able to compile and send the progress report from a terminal.

The system Don and his colleagues demonstrated had an eery number of similarities to today’s mobile radio networks despite its enormous size – a delivery van is much larger than an iPhone – and the relatively primitive nature of computers at the time:

- The LSI-11 was a miniaturized version of DEC’s PDP-11 minicomputer that was more portable and rugged because it was built out of VLSI circuits instead of the older, larger, and more power hungry medium- and large-scaled integrated circuits.

- The packet radio used spread spectrum transmission in a way that’s very similar to today’s Wi-Fi networks and CDMA cellular networks.

- Packet radio supplemented TCP error detection and correction with its own system of checksums and positive acknowledgements just as today’s Wi-Fi and cellular systems do.

- The radio network had a self-organizing, mesh network capability for flexibility as well as a more efficient centralized control point mode with directed routing.

- The system used TCP to bond dissimilar networks in a way that was transparent to the user, thus proving the practicality of TCP.

- It used the 1800 Mhz band that services downlink on today’s cellular networks.

- Channel bandwidth was 20 Mhz, about the same as standard Wi-Fi channels and not an unknown size for cellular.

This was the Internet’s birthday in the sense that it demonstrated TCP connecting dissimilar networks in a way that was transparent to users. The email the ARPA administrators received that day was no different in form and structure from an email sent from a terminal directly connected to ARPANET, and they didn’t require any special equipment to read it. When people use the expression “innovation without permission” this is what they mean: many new things are made possible on the Internet every day without causing immediate or massive disruption to existing equipment or applications, and some of these new things are new kinds of networks.

Don humbly submits that he and his team didn’t anticipate the web or the digital libraries that make information so readily available to use today, but there’s no doubt that their achievement cemented mobile networking into the heart of the Internet, accelerating a chain of innovations that lead us to today’s smartphones and their transparent integration with the rest of the Internet.

You can listen to the podcast here immediately, and next week it will be available on iTunes and the other platforms.

Happy birthday Internet, and thank you Don Nielson.

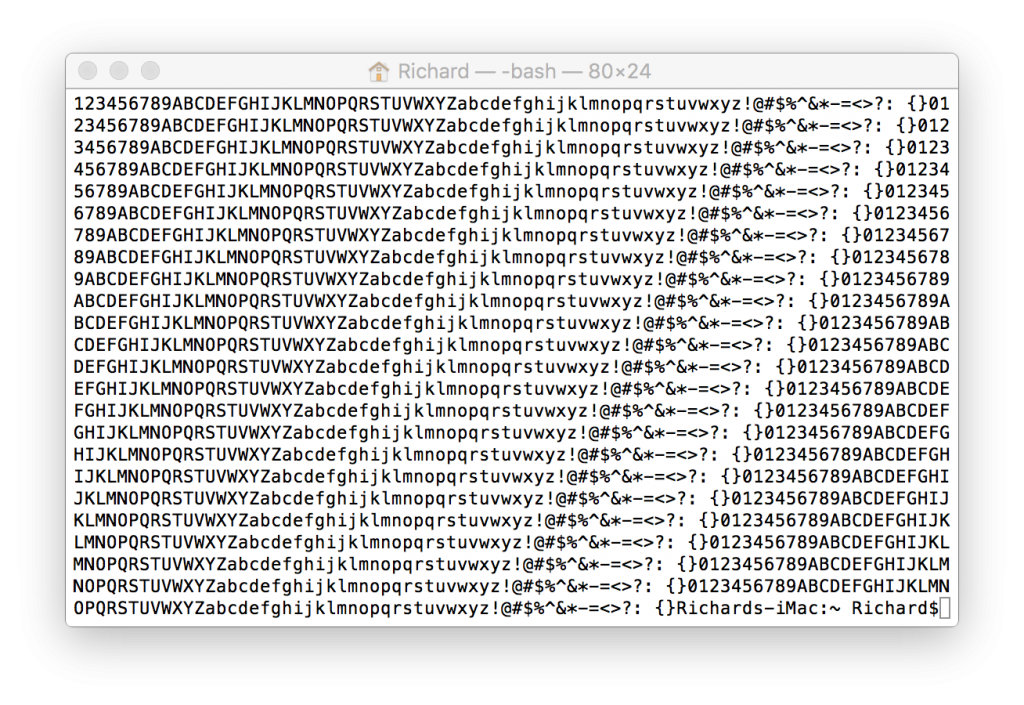

Here’s a classic barber pole test pattern as it would have looked in 1976. This test pattern makes it easy to detect both lost characters and lost lines. This is the receiving side of a test that sends a constant stream of characters from the sending side. Because the stream is continuous, the pattern scrolls and you can easily see errors.

[Note: I had to actually code this because Google image search doesn’t know what the heck it is.]