FCC Defeat Holds Chattanooga Train at the Station

While some advocates were disappointed by the FCC’s latest defeat in the courts, I doubt anyone was surprised. The facts are fairly simple: the same day that the FCC passed its current Open Internet Order, it also ruled that municipal utilities in Chattanooga, TN and Wilson, NC didn’t need to abide by state laws limiting their broadband services to the areas specifically permitted by state law. The agency’s attempt to override state laws was not viewed as likely to be deemed lawful at the time, although some of the clickbait bloggers engaged in some wishful thinking.

FCC Action an Administration Initiative

Like the Title II classification of broadband, the state law preemption action conformed to the wishes of the Administration. As President Obama said in a speech in Cedar Falls, Iowa a month before the FCC’s action, state laws restricting muni broadband have to go:

And if there are state laws in place that prohibit or restrict these community-based efforts, all of us — including the FCC, which is responsible for regulating this area — should do everything we can to push back on those old laws. I believe that’s what stands out about America — this belief that more competition means better products and cheaper prices. We do that with just about every other product. We ought to be doing it with broadband. It’s just common sense.

So the FCC’s preemption order was an attempt to see how far the Administration’s FCC could go.

The Mystery of Section 706

Perhaps the FCC was encouraged by the fact that the DC Circuit Court had suggested in its order nullifying the 2010 Open Internet Order that Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act gave it an almost unlimited remit to promote broadband networks. It directs the FCC to study broadband deployment, and if it finds things are not going as well as they should, it “shall take immediate action to accelerate deployment of such capability by removing barriers to infrastructure investment and by promoting competition in the telecommunications market.”

While it’s not spelled out in Section 706 (because it’s understood as part of the context for the law,) the FCC’s powers of deregulation are generally limited to regulations that affect private sector investment. The 1976 pole attachment law, for example, only pertains to private actors:

(1) The term “utility” means any person who…owns or controls poles, ducts, conduits, or rights-of-way used, in whole or in part, for any wire communications. Such term does not include…any person owned by the Federal Government or any State.

Since cities are political subdivisions of states, they’re covered under “owned by any State.” So the FCC’s 706 powers were correctly understood as limited to deregulatory action that would promote private investment and competition among private players in spite of the court’s language in the termination of the 2010 Open Internet Order.

Does the FCC’s Defeat Matter?

Muni broadband supporters strongly believe that local government is the best possible supplier of broadband networks, and point to success stories such as Chattanooga to make their case. Even the court opinion vacating the FCC’s muni networks order declares that the Chattanooga network has produced enormous benefits to the community in terms of job creation, general economic stimulus, and even a better bond rating:

The EPB’s fiber-optic network has received uniform praise. It has led to job growth and attracted businesses to the area. Its introduction led established Internet providers to lower rates while increasing the quality of their services. The fiber network has also put more money in Chattanooga’s coffers, which contributed to Standard and Poor’s upgrading of the EPB’s bond rating to AA+ in 2012.

But these claims are peculiar. Chattanooga has said it wanted a gigabit fiber network (in addition to the AT&T U-verse and Comcast cable networks it already had) in order to attract new businesses to the area, especially tech startups:

As cities across the U.S. have begun building out their own high-speed networks, Chattanooga stands apart in fiber-to-the-home connectivity. With more than 80,000 homes and businesses connected to ultra high-speed internet, our region is the ideal environment for testing applications that will thrive on the advanced broadband platforms now in development throughout the nation.

And city leaders tout job growth since the network was installed. But just because thing B happens after thing A doesn’t mean thing A caused thing B.

Developing a High Tech Economy

While the Gig City branding helped raise Chattanooga’s profile higher than it has been since the song “Chattanooga Choo Choo” was released, it’s hard to argue that a 10 Gbps network is a necessary or sufficient condition for the development of a high tech economy.

Silicon Valley doesn’t have an astoundingly unusual array broadband networks: apart from a dozen apartment buildings, broadband service from San Jose to San Francisco is either AT&T U-verse or Comcast, just as it was in Chattanooga before the local power board built its fiber-to-the-home network with support from a sizable federal grant as well as a local bond issue:

Federal taxpayers are on the hook for the $112 million stimulus grant, plus an estimated $46 million in interest. EPB’s electric customers are footing the bill for more than $390 million in bond payments to help cover construction costs related to the fiber network.

That’s a lot of money for a network that only serves about 60,000 people: about $11,000 a head, enough to pay for triple play for five to ten years, at which time the network’s users may be ready to move on to 5G.

Putting Your City On the Map

But the Gig City labeling did make people aware of Chattanooga, a nice little town by most accounts; its Lookout Mountain is a tourist attraction famous throughout Tennessee, as I recall from my boyhood in Morristown, TN. Morristown, BTW, was the first Tennessee city to get a city-owned and financed FTTH network. The Morristown FiberNet was built in 2005 and serves about half the city’s telecom users today with a product mix of TV, telephone, and Internet. Cox Cable serves the other half, and the two services compete for customers with comparable services and prices.

Morristown isn’t on the map especially, but it’s a nice little bedroom community for people who work in Knoxville. Its 10 + year history explains part of the state’s reasoning for restricting broadband networks built by utilities to the utility’s footprint. While it’s easy to sneer at Tennessee legislators as hapless lapdogs of telecom lobbyists, the state does have an extensive history with muni networks, not all of it rosy. So it’s not unreasonable to limit the size and scale of muni networks, although networks to have economies of scale.

And it certainly is the case that a number of people in hilly Tennessee are underserved by market-financed broadband networks. Today’s broadband economy is a hybrid of market-based and subsidy-based systems, and that’s not likely to change very soon.

Appropriate Expectations

While I’m not equipped to judge muni broadband on an economic basis, as a technologist it appears to me that muni systems tend to do a very poor job of writing specifications, setting expectations, and signing up new users. This begins with the current mania for gigabit (1,000 megabits per second) networks in a world in which web servers can’t deliver pages faster than 15 Mbps on average and Netflix streams consume less than 4 Mbps. Telling people that web surfing is “blazingly fast” on gigabit networks is deceptive advertising that we generally wouldn’t tolerate from commercial network providers.

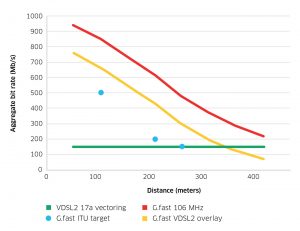

The average download speed for US broadband networks is now 55 Mbps according to Speedtest.net and 67.8 Mbps according to Akamai (Average Peak Connection Speed.) Cisco has just developed a system that will allow cable to offer multi-gigabit/second symmetric speeds over standard coaxial cable, and G.Fast DSL is approaching a gig over copper pairs.

Given that the performance of web servers is advancing much more slowly than network performance, investment in ultra-high-speed wired networks is a debateable point that should be balanced against other spending priorities.

The 5G Revolution is Coming

And there’s also the problem of 5G. If a wireless gigabit technology is right around the corner, do we really want to be investing in gigabit fiber to the home that we’re only going to use for five years, or maybe ten? From the standpoint of convenience alone, I’d rather have wireless than any kind of fiber. But it’s certainly nice to have some fiber in the neighborhood, and if there’s no wire there at all it may as well go all the way to home, especially if someone else is going to pay for it.

I’ve personally just downgraded my wired connection from 100 Mbps to 50 and didn’t see any difference. This was a budget move motivated by a desire to use a robocall-blocking service that needed a feature from my phone service, simultaneous ringing, that happens to be an extra cost option from my telecom provider. So I upgraded the phone service, downgraded the broadband service, and now have a robocall blocker and the same Internet experience as before. So happiness comes in a number of shapes and sizes.

The point is that broadband speed, while nice, is not the only thing that matters to Internet users: We care about reliability, security, and flexibility as well. Turning broadband service over to public utilities is probably not the best way to get to 5G. And contrary to the claims of some who ardently believe our broadband service must be supplied by government agencies, 5G is the future of communication.