House Set to Aggravate Internet Problems

It’s only been a year since the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, so we shouldn’t be surprised that Congress hasn’t done anything about the Internet’s privacy problem yet. Big problems like this take time to address, and it’s better to move slowly than to rashly make matters worse the way Europe did with the ill-conceived GDPR.

For the time being, Internet privacy is overseen by the Federal Trade Commission, which enforces uniform standards for the collection and use of consumer Internet data all the way from keystroke to data broker to social network. The House Communications and Technology Subcommittee promises to change this, however.

The Save the Internet Act of 2019 comes up for markup Tuesday, March 26th. This bill seeks to restore the regulatory status quo as it existed at the end of the Obama Administration. That’s a big problem for privacy because it deregulates ISP data collection practices.

The Obama ISP Privacy Regulations Were Repealed

The Title II (“Open Internet”) order reclassified ISPs under Title II of the Communications Act, the designation created for Telecommunications Carriers. Under the FTC Act, telecommunications carriers are exempt from Trade Commission regulation.

The Obama FCC knew this, of course, so it passed a lame duck privacy order of its own to close the doughnut hole in America’s privacy law. Using the Congressional Review Act, Congress repealed this order before it took effect.

The Trump FCC resolved the deregulation of ISP data collection practices by returning ISPs to Title I Information Service status. This reinstated the FTC’s traditional authority and ensured that ISPs would be regulated in the same way that Cambridge Analytica-related companies such as Facebook and Google are.

Scaring People Across the Political Spectrum

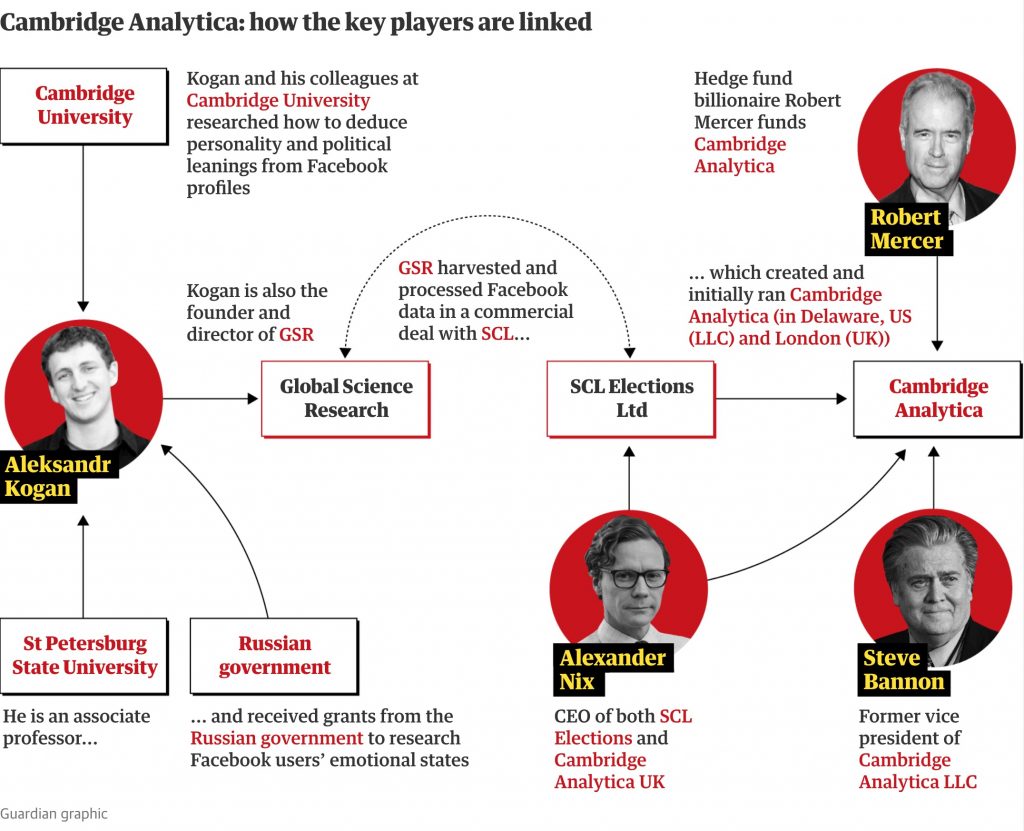

The Facebook data leak to the Trump Campaign by way of Cambridge Analytica terrified a lot of people because of the players involved. The Facebook data included social graphs reaching more than 50 million people collected by Aleksandr Kogan, a researcher partially supported by Russia.

Kogan sold the data to Cambridge Analytica, a company headed by Alexander Nix and Steve Bannon, and they sold it to Brad Parscale, the 5G-hating data cruncher at the Trump Campaign. So the entire political left and center were immediately freaked out.

As subsequent hearings discovered, these data brokering practices were anything but unique: the Obama and Clinton campaigns also had data gathering and voter targeting operations, but they were just less effective. But they were just as scary to the right as the Trump campaign’s tactics were to the rest of the country.

We’ve Come a Long Way Since Cambridge Analytica

We’re ahead of where we were a year ago on the data privacy issues behind Cambridge Analytica: there have been a number of hearings on both sides of the Atlantic and multiple investigations. We’ve learned that Facebook knew about Cambridge as early as September, 2015, long before it was reported.

We’ve learned that consumer data has its own supply chain with data brokers acting as hubs that collect data from multiple sources and disseminate it to multiple aggregators. As more parties analyze personal data, the more sensitive it becomes.

Congress is doing its part with an Honest Ads Act, but it’s yet to pass. The FTC is opening an investigation of tech industry business practices, and a number of presidential candidates want Silicon Valley’s head on a pike. California has passed an extreme privacy law set to take effect next year. And Europe is cracking down on digital piracy.

The Technology Industry is Redesigning Itself

Lest we forget that technology emerges from labs rather than Congressional hearings, it’s worth noting significant changes afoot in Silicon Valley. Facebook plans to build its future on messaging rather than news feeds.

Apple has unveiled a broad array of new service offerings for news, movies, and gaming. Google is launching a gaming platform that largely redirects the YouTube infrastructure to subscription-based revenue models rather than parasitic content and ads.

While money has been flowing into Hollywood for the creation of new video content for streaming platforms for some time, Silicon Valley is embracing a broader set of products that emphasize communication and real-time interactions such as gaming. This new focus will heighten the traditional tension between the web’s form of data transmission and applications with more stringent requirements.

The Rise of Real-Time Calls Net Neutrality Into Question

Net neutrality has always been the lazy man’s shortcut to antitrust enforcement. This is by design, because net neutrality inventor Tim Wu is more interested in winning antitrust cases than in ensuring the Internet will flourish.

Wu and people like him – such as the Public Knowledge analysts – are upset that US antitrust law makes it harder than they’d like it to be to win discrimination cases. If you have to analyze when and why service quality can be sold for a fee over and above “normal” transmission quality, winning cases depends on knowledge of engineering and economics.

They would rather these cases be decided by rules prohibiting potentially destructive tactics than by motivations, prices, and overall effects. Hence their desire to ban “paid prioritization” across the board rather that examining specific service plans in the context of consumer benefits and effects on innovation.

This is the Worst Possible Time to Restore the Obama Regulations

There is no good reason for Congress to move forward with attempts to restore the Title II (“Open Internet”) regime at this time. It complicates privacy regulation by requiring the FCC to violate the CRA resolution vacating the Obama ISP privacy regime, a legally untenable demand.

The proposed bill also makes it practically impossible for smaller companies to compete with Apple, Google, and Facebook for gaming and video conferencing. And the unintended side effect of the paid prioritization ban is to make 5G network slicing impossible to price and deploy.

So why try to recreate a status quo (that wasn’t at all good) instead of skating to where the puck is going? The only reason for Congress to turn the clock back to 2015 is to enjoy the comfort of a well-worn path. This is cowardly and counter-productive; the rank and file should say “no” and demand a more serious approach to Internet regulation from their party leadership.