Who’s making money on the Internet?

One of the background questions in Internet policy debates concerns what and who contributes value to the overall system and who extracts profits. In a perfectly functioning market, profits will reward innovation, investment, and the creation of value for users; but there are very few perfect markets. A number of things distort market efficiency: government policy is certainly one such thing, and market power is another.

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) is one very good way to evaluate competition, profitability, and leverage in capital-intensive businesses. The Morningstar Investor’s Classroom explains its significance in the following terms:

The best way to determine whether or not a company has a moat is to measure its return on invested capital (ROIC). This is similar to [Return on Assets] but is a bit more involved. The upshot is it gives the clearest picture of exactly how efficiently a company is using its capital, and whether or not its competitive positioning allows it to generate solid returns from that capital.

According to Morningstar, firms with 15 percent or more ROIC for a number of years are most likely have a “moat” that protects them from competition.

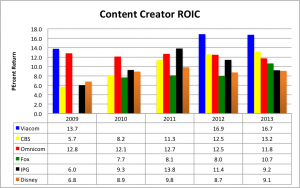

So let’s look at three sectors: content creators such as Disney and Viacom who create the movies and TV shows that we stream into our homes; network services firms such as Comcast and AT&T who provide us with broadband networks; and Internet “edge services” such as Netflix and Google, who connect network users with content and services.

US Internet policy has emphasized the creation of “edge services” intermediaries since the mid-90s, through a number of policy initiates such as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (Title V of the Telecommunications Act of 1996), a law that provides relieves edge providers of liability for the side-effects of publishing unlawful information such as libel and copyright violations. The relevant part of this law says: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” Another provision that is intended to stimulate the market for “edge services” is net neutrality, which shifts communications costs from edge services to consumers and eliminates network services enhancements that might enable more kinds of edge services that those we already have.

So how do the sectors do?

Content Creator. Among content creators, only Viacom produces ROIC greater than 15 percent, just breaking that threshold in the last two years.

US-Based Content Creator Return on Invested Capital

Note: Viacom’s net operating profit after taxes was negative in 2010–11, so we do not have ROIC figures for Viacom for those years.

Source: Bloomberg Professional Service.

Viacom’s Paramount Pictures unit produces unusually large profits through an unconventional approach: it produces fewer movies than its rivals, but more profitable ones:

Paramount ranks last among major studios (and even behind the mini-major Lionsgate) in the annual box-office race, with under $900 million to date in domestic ticket sales, down by half from its recent peak in 2011. Yet Paramount has become consistently profitable in an industry where profit margins have ranged from razor-thin to nonexistent.

None of the other content creators produces such high returns on invested capital.

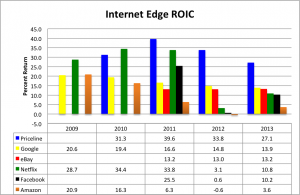

Internet Edge Services. Among Internet edge providers, Priceline is effectively insulated from competition for the time being, but its position has eroded steadily since 2010, as has Google’s.

Netflix’s ROIC has declined sharply since it has begun to invest in content and in a content delivery network, but the major part of its long-term ROIC outlook comes from its pivot from DVD rentals to streaming. Despite consumer preference for streaming, which has accounted for most Netflix revenue since 2013, DVD rental is a more profitable business; Netflix margins are 50 percent on DVD rental but only 25 percent on streaming. Streaming produces more total profit because more people do it.

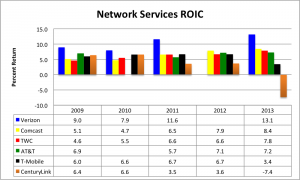

Network Service Providers. The network services sector does not contain a player who meets Morningstar’s long-term 15 percent ROIC moat standard, and it is fair to say that networking firms are jealous of the returns content and edge services firms earn. Verizon leads the sector with 2013 ROIC of 13.1 percent, not far below Google’s 2013 value. This data point is an anomaly for both Verizon and the sector as a whole, however, as the average ROIC for the sector is a quite modest 6.4 percent.

CenturyLink’s −7.4 percent ROIC is the largest negative value in the survey, beating Amazon’s −0.6 percent 2012 value by an order of magnitude. Clearly, networking firms invest more heavily and achieve lower returns than firms in the content and edge services segments.

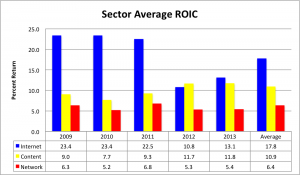

Summary. Averaging ROIC across all firms in each sector and then comparing sector averages confirms the impression that the Internet edge sector is most profitable and best protected from competition. Using Morningstar’s criterion of ROIC in excess of 15 percent for several years constituting a moat, Internet edge providers are protected from competition; they have averaged 17.8 percent ROIC over the past five years.

Thus, Internet firms have produced 63 percent greater return on invested capital than content creators and 178 percent greater return than network service providers. There is clearly no factual basis on which to charge networking companies with being excessively profitable.

Question. Does the imbalance of profitability between content creators, network service providers, and Internet edge services suggest that the initiatives of the mid-90s have been successful and can now be abandoned? This is the question that every subsidy raises.

Lawmakers placed a finger on the scale to stimulate one sector of the Internet economy. At what point to we declare victory and allow the market to develop according to the expressed preferences of buyers and sellers? The continuing drive to create an enforceable net neutrality law would be one way to continue the distorted market, and the continuing drive to turn a blind eye to movie piracy is another.