Unclouded Vision

Abstract:

The commercial reality of the Internet and mobile access to it is muddy. Generalising, we have a set of cloud service providers (e.g., Amazon, Facebook, Flickr, Google, Twitter, to choose a representative few), and a set of devices that many, and soon most, people use to access these resources (i.e., so-called smartphones such as Android, Blackberry, iPhone, Maemo). This combination of hosted services and smart access devices is what many people refer to as “The Cloud” and is what makes it so pervasive.

But this situation is not entirely new. Once upon a time, as far back as the 1970s, we had ‘thin clients’ such as ultrathin glass TTYs accessing timesharing systems. Subsequently, the notion of thin client has resurfaced in various guises such as the X-Terminal, and Virtual Networked Computing (VNC)[9]. Although the world is not quite the same now as back in those thin client days, it does seem quite similar in economic terms.

But why is it not the same? Why should it not be the same? The short answer is that the end user, whether in their home or on the top of the Clapham Omnibus, has in their pocket a device with vastly more resource than the mainframe of the 1970s by any measure, whether processing speed, storage capacity or network access rate.

Meanwhile, the academic reality is that many people have been working at the opposite extreme from this commercial reality, trying to build “ultra-distributed” systems, such as peer-to-peer file sharing, swarms, ad hoc mesh networks, mobile decentralised social networks , in complete contrast to the centralisation trends of the commercial world. We choose to coin the name “The Mist” for these latter systems. Haggle[12], Mirage[7] and Nimbus[10] are examples of architectures for, respectively, networking, operating system and storage components of the Mist.

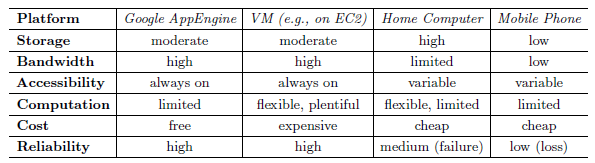

These approaches are extreme points in a spectrum, each with its upsides and downsides. We will expand on the relevant capabilities of two instances of these ends subsequently; Table 1 summarises them.

Table 1: Comparison of different platforms to store and handle personal data.

Authors:

Jon Crowcroft, Anil Madhavapeddy, Malte Schwarzkopf, Theodore Hong

Cambridge University Computer Laboratory

15, JJ Thomson Avenue

Cambridge CB3 0FD, UK

firstname.lastname@cl.cam.ac.uk

Richard Mortier

University of Nottingham

Jubilee Campus

Nottingham NG7 2TU, UK

firstname.lastname@nottingham.ac.uk

The Cloud: Benefits

Centralising resources brings several significant benefits, specifically:

• Economies of scale,

• Reduction in operational complexity, and

• Commercial gain.

Perhaps the most significant of these is the offloading of the configuration and management burden traditionally imposed by computer systems of all kinds. Additionally, cloud services are commonly implemented using virtualisation technology which allows such efficiencies of scale while still retaining “chinese walls”, isolating users with no right to see each other.

The Cloud: Costs

Why should we trust a cloud provider with our personal data? There are many ways that they might abuse that trust, notwithstanding that most operate within jurisdictions implementing various forms of data protection legislation. The waters are further muddied by the various commercial terms and conditions to which users initially sign up, but which providers often evolve over time. When was the last time you checked the URL to which your providers will post alterations to their terms and conditions, privacy policies, etc.? In such cases, how can we get our data back and move it to another provider, also making sure that they have really, really deleted it?

The Mist: Benefits

Accessing the Cloud can be financially costly due to the need for constant high-bandwidth access. Using the Mist, we can reduce our access costs because data is stored locally and need only be uploaded to others selectively and intermittently. We keep control over privacy, choosing exactly what to share with whom and when. We also have better access to our data: we retain control over the interfaces used to access it, we are immune to service disruptions which might affect the network or cloud provider, and we cannot be locked out from our own data by a cloud provider.

The Mist: Costs

Ensuring reliability and availability in such a distributed decentralised system is extremely complex. In particular, a new vector for breach of personal data is introduced: we might leave our fancy device on top of the aforesaid Clapham Omnibus with our data on! We have to manage the operation of the system ourselves, and need to be connected often enough for others to be able to contact us.

Droplets: A Happy Compromise?

In between these two extremes should lie the makings of a design that has all the positives and none of the negatives. In fact, a hint of a way forward is contained in the comments above.

If data is encrypted both on our personal computer/device and in the cloud, then we don’t really care where it is stored for privacy reasons. However, as a user, we do care where it is stored for performance reasons. Hence we’d like to carry information of immediate value close to us. We would also like it replicated elsewhere for reliability reasons. Further, we observe that interest/popularity in objects is Zipf-distributed. We also observe that the vast majority of user generated content is of interest only within the small social circle of the content su

[…] another reason to read Unclouded Vision. IBM: Biggest threat to the cloud could be security issues | VentureBeat The number of exploitable […]