Silicon Valley in the Crosshairs of Regulation

I’m seeing a bit of pullback from the usual optimism about technology and tech policy since the failure of the Shadow Inc. IowaReporterApp. This is the app built by a Denver-based company staffed by veterans of the 2016 Clinton campaign that wasn’t tested before caucus night.

The app had a very simple job: authenticate precinct captains, collect three numbers, put these numbers into a simple database, and say “thank you.” I wrote a much more complicated app in 1977 for the J. C. Penney catalog order system that collected catalog orders over dial-up phone lines, so this isn’t rocket science, brain surgery, or even hard coding.

Given that the final version of the app wasn’t released until three days before the caucus and it was only tested in the most perfunctory way, the result was perfectly predictable. Even if the app had been perfect – which it wasn’t – you can’t expect 1700 untrained volunteers to use a new app correctly without help.

Fallout

Andrew Yang is pointing out that voters are skeptical about entrusting their government to operate complex entitlement systems if it can’t even count votes.

Presidential candidate Andrew Yang calls the Iowa caucus fiasco an “avoidable error that shot the party in the foot.”

“It is going to be harder to convince Americans that we can entrust massive systems with government if we can’t count votes on the same night…” #CNNTownHall pic.twitter.com/x0YaT0477T

— CNN (@CNN) February 6, 2020

The memory of the Obamacare website still haunts us.

J. Alex Halderman, a professor of computer science at the University of Michigan, took the occasion to denounce voting apps in general: “This is an urgent reminder of why online voting is not ready for prime time.” That’s going too far because this isn’t a voting app, it’s just a reporter.

Reaching Beyond the Caucus Problem

Given that one of the major political parties has failed to deploy a simple app for an important job – and not for the first time – skepticism mounts on the Internet policy front. It has now become clear that regulators were asleep at the switch for ten years prior to adopting more aggressive stances they took on the AT&T/Time Warner Media merger and on Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica fiasco.

In 2007, the FTC approved Google’s anti-competitive takeover of DoubleClick; in 2011 it was permitted to buy AdMeld, an advertising competitor; and in 2012, the FTC refused to follow a staff recommendation to sanction the search giant for anti-competitive practices.

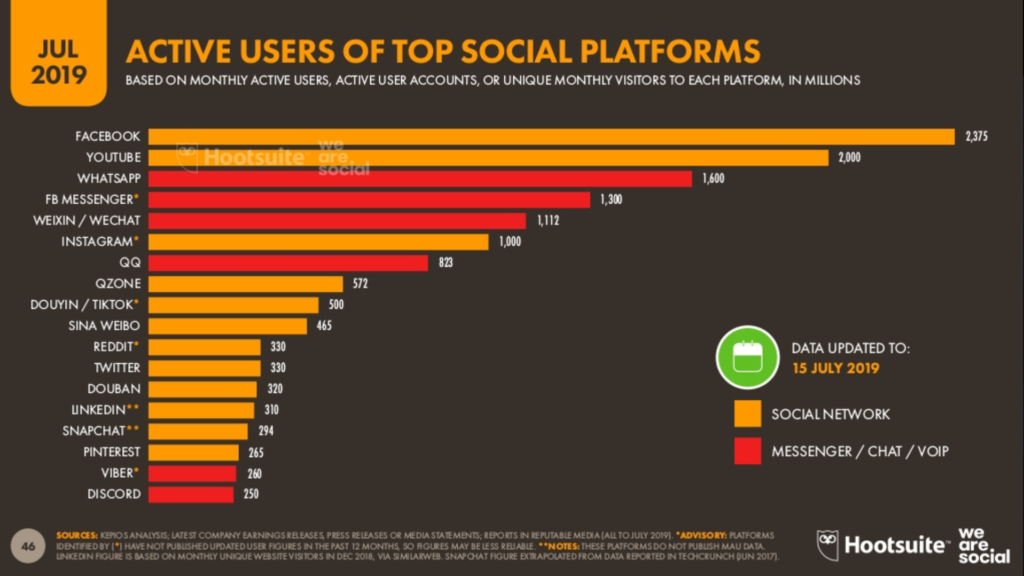

Facebook bought Instagram for a billion dollars in 2012 and WhatsApp for $19B in 2014. The FTC approved the Instagram takeover without a hitch and only gently reminded Facebook of WhatsApp’s privacy promises while issuing a speedy approval of the larger deal. TechCrunch recognized Instagram was a “budding rival,” but public interest concerns about the WhatsApp takeover were limited to privacy fears.

Today, Facebook owns three of the top four social platforms and four of the top six. Given that half of Facebook’s platforms and Google’s sole one (YouTube) were purchased rather than developed internally, the casual acceptance of these mergers by both the public interest and the regulators is simply bizarre.

Correcting Past Errors

The connection between the Iowa fiasco and laissez faire attitudes toward Google’s and Facebook’s growing-by-purchasing-budding-competitor strategies is the failure to understand technology risks and opportunities. Lawmakers will never “understand” technology, but they’re in a much better position to understand technology markets.

For a long time, the digital economy was considered to be magic by lawmakers. Tech companies provide good-paying, clean jobs at a time when traditional industries are considered damaging and exploitive. High skill tech jobs are also harder to move overseas than low skill manufacturing jobs; or so says conventional wisdom.

This Tuesday, the FTC unanimously voted to open an inquiry on the large tech mergers it approved after 2010, to the delight of lawmakers:

“Today’s decision by the FTC to examine past acquisitions by dominant technology companies is an important step in correcting the decades of inaction by antitrust enforcement agencies that have led to consolidation in the digital marketplace and across almost all sectors of our economy,” Rep. David Cicilline (D-R.I.), who is leading the House investigation, said in a statement.

The inquiry will need to determine whether these deals were made for legitimate purposes (such as increasing efficiency and product quality) or for illegitimate ones, such as stifling budding competitors to better control markets. Now that the blush is off the tech rose, this is going to be an interesting inquiry.