Modularity vs. Integration in Entertainment Design

Last time I discussed the high points of modularity and integration in personal computer design, in particular the benefits that Microsoft hopes to gain by integrating personal computer hardware of its own design with its Windows operating system. With that as background I’d like to take a look at integration in corporate mergers and acquisitions. These subjects really are related, so bear with me.

Facebook Acquisitions

Some of America’s largest companies have achieved their size and scale by simply buying up potential competitors before they got so big as to become threats. Notorious recent examples are Facebook buying up Instagram for $1B and then WhatsApp for a whopping $22B.

The Instagram deal brought 50 million new customers to Facebook for $20 apiece, while the WhatsApp deal brought in 450 million for $50 a head. While both of these deals were touted by Facebook for the talent and experience they brought to the company, analysts viewed them as defensive moves, shielding Facebook from potential rivals:

That indicates Facebook bought WhatsApp to add value to its existing messaging services, as well as for the long-term potential of the company.

Facebook bought Instagram for $1 billion in 2012 for similar reasons: As young social network users gravitated towards photo-sharing, Facebook wanted to scoop up what could have eventually become a big rival.

WhatsApp has also turned out to be valuable resource for advertising data. WhatsApp had a strict privacy policy, one that Facebook promised to honor. But that promise didn’t last long, and now WhatsApp tells Facebook its users’ phone numbers, device information and messaging metadata.

Both of these acquisitions were approved by regulators with no significant conditions.

CenturyLink Acquisitions

CenturyLink follows a different strategy to acquisitions: rather than buying up potential rivals, it seeks to realize economies of scale. Today’s CenturyLink is descended from a small, rural phone company in Louisiana, the Oak Ridge Telephone Company. In 1930, 75 customer ORTC was sold for $500 to an entrepreneur who located its switch in his parlor. He passed it on to a son as a wedding present and the rest is history.

The company, now known as CenturyLink, bought Qwest Communications in 2010, becoming the nation’s third largest phone company. Subsequent acquisitions have targeted cloud services as most of the low-hanging fruit in the telephone business have been picked.

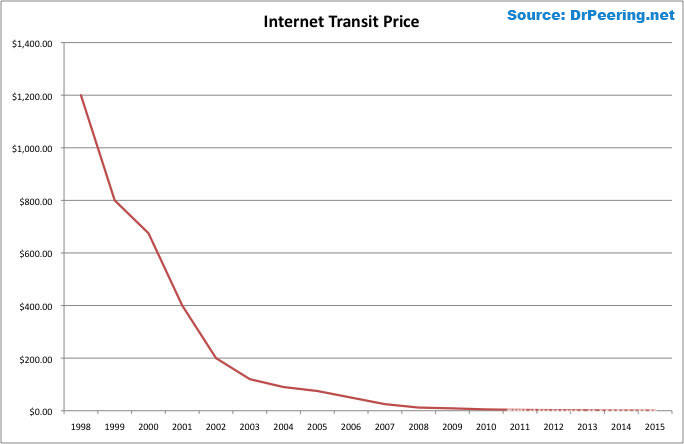

CenturyLink’s proposed merger with Level 3 increases revenue and requires the company to take on substantial debt. Level 3 is in the very hard business of Internet transit, where prices are falling faster than costs and expansion are costly.

This acquisition will enable CenturyLink to convert a cost center to a business center, so it amounts to in-sourcing Internet transit. And it also brings some CDN customers to CenturyLink.

Overall, this merger is viewed as refocusing CenturyLink on business telecommunications services. The company will become a one-stop shop for telecommunications, transit, and CDN services with a national and even international footprint. Regulators will look a the deal and probably approve it without significant conditions. CenturyLink will pay $34B in cash and stock and gain 200,000 miles of fiber and CDN assets.

Owning a large fiber network also enables CenturyLink to explore other opportunities in wireless networking such as 5G for either residences or businesses. Perhaps T-Mobile or Sprint is its next target. But perhaps not for a while.

Qualcomm Acquisitions

Qualcomm is a firm that has used acquisitions to bring expertise in-house that it deems critical to future growth. When Wi-Fi took off, Qualcomm purchased Airgo Networks, a Wi-Fi chip vendor that offered a chipset that was easy to integrate into gaming devices (Disclosure: I worked at Airgo in its early days, when it was known as Woodside Networks.) It then supplemented its Wi-Fi expertise by taking over Atheros, the producer of a lower cost, CMOS-based chipset favored by the open source community.

More recently, Qualcomm acquired Bluetooth vendors Stonestreet and CSR, and is currently moving to acquire NXP, a chipset vendor active in the Internet of Things space. None of these plays raise regulatory concerns, and they’re consistent with a long-standing strategy of bringing expertise in-house through acquisition to fuel growth in new markets.

AT&T Acquisitions

Much like Oak Ridge, today’s AT&T is the product of a relatively small telephone company, Southwestern Bell, achieving scale through a series of acquisitions. The company now has the second largest mobile network. The company now proposes to acquire Time Warner, the nation’s fourth largest entertainment company.

Like the CenturyLink merger with Level 3 and unlike the Facebook acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram, this merger has no particular competitive implications. It’s a vertical merger between non-rival firms and not a move intended to protect the companies from competition.

Regardless, the usual critics of telecom mergers are sharpening their knives in an attempt to carve out some concessions from the national and international regulators who will examine the deal.

One example of the criticism is a piece by law professor Susan Crawford, who wrote a book on the merger of Comcast with NBC Universal. Crawford’s critique maintains that AT&T faces no competition (…the company faces no real competition, paragraph 1) and also that AT&T has refused to invest in its U-verse television service because it faces too much competition: “U-Verse isn’t an effective competitor to cable’s data offerings” (paragraph 6).

Criticisms of this sort suggest that the critics opposing the merger don’t care about the details as much as that they oppose mergers on the principle that large firms are inherently untrustworthy. As Crawford puts it:

The new problem—the merger-specific problem the deal prompts—is that it will give AT&T even more of an incentive to beat up potentially competitive sources of content in a gazillion ways.

This criticism doesn’t appear to be on point. The proposed merger doesn’t have implications for competition. Obviously, AT&T will benefit from continuing to distribute Time Warner content as broadly as possible and by continuing to enable its users to view content from other sources.

Modularity and Integration

Traditionally, television programming has been distributed in the broadcast mode, whether by wire or over-the-air. The broadcaster simply transmits a single copy of each program to all the receivers that happen to be tuned in to the channel on which the transmission takes place.

We’ve in the midst of a transition from broadcasting to unicasting, where each consumer sees an individual copy. This change in technologies puts the consumer in charge of the programming and imposes steep costs on the transmitter. But it also opens up new avenues for advertising because the unique copy of the program can be customized to the user’s preferences. This new mode of distribution also enables the network to know which users are watching which programs at any given time.

Just as Microsoft and Apple see benefits from making both the software and the hardware that its users employ, creators of entertainment (a kind of software) see benefits in managing the networks over which these programs are carried, the hardware.

If it’s rational for Microsoft to take control of the hardware under its operating system, it’s probably also rational for the Time Warner entertainment content to be well integrated into the AT&T network. Microsoft has the example of Apple to follow, especially important because Apple has beaten Microsoft in the laptop and phone market for several years. But our analogy isn’t perfect.

Realizing the Benefits

If AT&T simply treats Time Warner and its wired and mobile networks as distinct business module with no cross-pollination, it will accrue increased earnings, a heavy debt load, and no large-scale benefits. I don’t think this is the plan.

It’s more likely that AT&T will use Time Warner’s entertainment as proof of concept material for changes to its network architecture. Unicast delivery of a massive data load – which is what TV is – requires staging (or caching) of the content at several points in the network. If AT&T doesn’t have to worry about license agreements with Time Warner, it can conduct a series of experiments to discover the optimal location of these staging points, perhaps slicing and dicing the content in several locations around the edge of the network (or even in consumer equipment.)

Having a library of content in-house also enables AT&T to develop some new ways to monetize content, one of the perpetual conundrums of the Internet. It’s practical to overlay ads on entertainment, or to frame the entertainment inside of ad banners, and even to customize scenes in the content with product placements.

All of these things feel creepy, but they’re all being done in one way or another in movie and TV production. Local ads are an important part of the revenue stream for cable companies, and the personal ad is simply hyper-local.

An integrated entertainment company can also enable users to construct split screens for multitasking. If you like to watch TV with an iPad on your lap, you already understand what that means and probably how it can be made better. With one firm in charge of content and presentation, seamless multitasking is possible.

Personalization

The most significant benefits of integrating content and carriage will probably come from personalization. This includes, but isn’t limited to advertising as noted. Personalized ads placed in response to multitasking activities are beneficial to users because they have relevance.

But the benefits don’t stop there. When the content creator can learn which scenes capture users’ attention to the extent that they replay them, it gathers insights that can be put to work in the creation of future programs. Similarly, if content creators can know which programs are abandoned by viewers and why, they may learn something about consumer preferences that can lead to better programs.

Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality

Augmented reality has been an expected new technology for a dozen years without much action. This changed with the advent of Pokémon GO in July. P-GO is the first AR app to achieve broad adoption, and it won’t be the last. AR (and its companion technology VR) are built on creative content that, like movies, engages the user in an adventure. This is not the kind of thing that Silicon Valley is good at, so the broad adoption of AR/VR requires some changes in the way that high tech products are developed.

AR is new form of entertainment, combining story telling, gaming, and technology to create an immersive experience. It stands to reason that the creative people at firms like Warner Studios have talents that will be important for new AR experiences. AR is also a mobile experience that requires the transfer of large video files, so the current assets of AT&T and DirecTV are perfectly located in that wheelhouse.

AT&T may seem too stodgy and buttoned-down to take the lead in the AR space, but the company has surprised a lot of people with its forward looking moves ever since it signed up to the be the first US network to offer the iPhone. Like video over mobile, AR is going to work best with rich content and network optimizations that move the content in real-time in response to user location and activity.

Conclusion

This is just scratching the surface, but it suggests that there are consumer as well as corporate benefits in the integration of content and carriage.

We won’t necessarily see the benefits all at once, but we have enough experience with integration in related technologies to feel confident they will be found. After AT&T re-configures its network to be friendly to Time Warner content, it will be better able to handle content from other sources better than it can today just as well. Ultimately, entertainment is entertainment regardless of who makes it.

But it’s good to have the freedom to innovate with personalization, tailored AR content, and efficient distribution.