FCC’s Broadband Label is a Loser

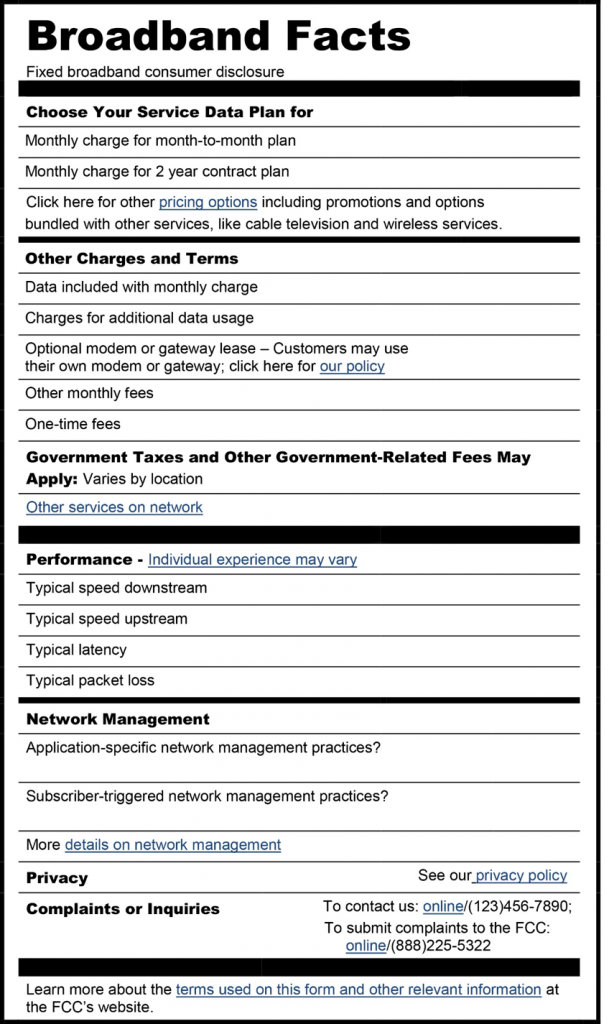

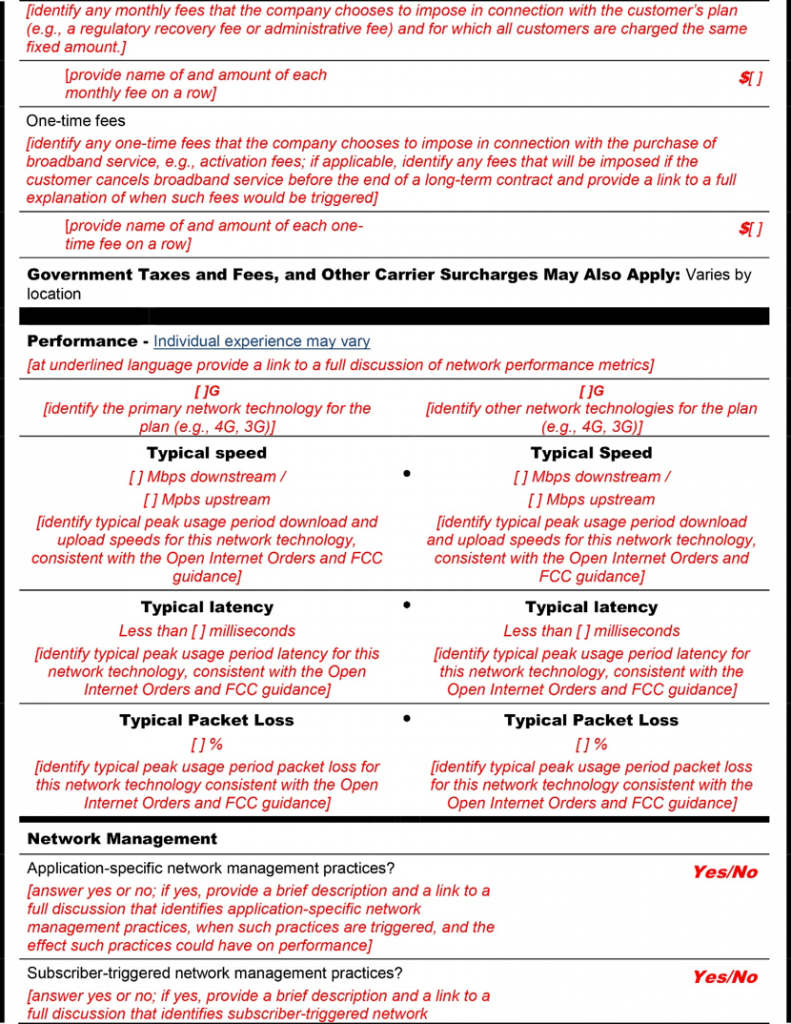

The FCC announced a broadband labeling program today that operationalizes the transparency provision of its Open Internet Order. In keeping with the agency’s preference for style over substance, the labeling program fails to provide consumers with useful information. The agency likes to compare it the nutrition labels required for food, and even copies the nutrition label format. The agency designed two templates, one for wired services and the other for wireless.

Instead of providing consumers with the kind of information the nutrition label discloses – macro- and micro-nutrients that have actual significance for health – these labels function more like the “Non-GMO” or “USDA Organic” labels that appeal to superstition and fail to guide consumers toward the kind of food products they should want to eat.

Junk Labels vs. Real Labels

The organic label, for example, reinforces the mistaken belief that some farmers are able to grow food without using pesticides, presumably because food pests wouldn’t be caught dead feeding on organic food. In reality, thousands of pesticides, some of them synthetic, are approved for organic farming and many of them are more toxic than their synthetic counterparts. And to top it off, organic foods are no more nutritious than scientific ones. But more on that another time.

The basic USDA nutrition label cuts through the misinformation about food and nutrition because it was created by scientists and reflects scientific concerns. The FCC broadband label is the result of a political process that has notoriously thrown engineering concerns to the winds. Its basic parameters were determined by Chairman Wheeler and the two Democratic commissioners, none of whom has an engineering background.

Ignoring Technical Advice

While the vague terms of the Open Internet Order could have been clarified by a technical consultation, the FCC chose to ignore technical input in favor of advice from the very non-technical Consumer Advisory Committee (CAC.)

The FCC established an Open Internet Advisory Committee under the 2010 Open Internet Order. It consists of engineers who work in the industry, non-profit, and academic sectors as well as a number of non-technicals mainly from the non-profit sector. Its current leader is Vice-Chairman David Clark, the MIT researcher who was the Internet’s chief architect in the 1990s.

While the OIAC could well interpret the ambiguous terms in this disclosure – latency and packet loss – the OIAC only meets when the FCC wants it to meet and it hasn’t wanted the OIAC to meet since Wheeler took over the agency from his predecessor Julius Genachowski.

The CAC consists of members with backgrounds in lobbying, policy development, and public relations rather than engineers. So it’s not the kind of group that can handle technical complexity.

The Label is Ambiguous

So what do the terms Typical latency” and “Typical packet loss” mean to the naive consumer and what do they mean to Internet engineers? Probably not even close to the same thing. Latency simply means “delay”, and it’s certainly important for real-time applications such as voice and video conferencing. It’s not at all clear what it means for video streams, however. It could be the time it takes for the consumer device to see the first packet in the stream of millions of packets that comprise a movie; but it could mean the delay until enough packets are transferred for the movie to start, and it could mean how long it takes to download the entire movie. Or it could be some sort of average of the elapsed time between a packet leaving the video server and arriving at the consumer device. Or it could mean something entirely different altogether.

In the case of voice, it’s simply long it takes each packet to travel from one end of the conversation to the other. This is important because when the delay exceeds 150 milliseconds on a regular basis call quality suffers and you get annoyed.

Latency

Latency is determined by three factors, only one of which is under the control of the ISP. These are equipment delays internal to the ISP network; equipment delays internal to the other network; and transit equipment delays in the interconnection of the two networks. The ISP can only control the first of these.

In addition to equipment delays – the time it takes a router or switch to switch from receiving a packet to transmitting it – there is the sheer delay in moving bits across a wire over a distance. This is mainly a function of the coefficient of propagation, which is some fraction of the speed of light. So no matter how good your ISP is in terms of limiting equipment delays, the longer your packets have to travel, the more “Typical latency” you’ll experience. You will also experience a lot of “Typical latency” if the parties with whom you communicate are on slow networks.

Packet Loss

Similarly, the “Typical packet loss” figure doesn’t tell you much about the ISP you’re evaluating because of the role that packet loss plays in the Internet’s congestion management systems. If you’re uploading a file faster than the receiving network can handle it, the receiving network will drop packets to tell you to slow down. Your ISP should record these packets as “lost” because they have to be retransmitted later on when the receiving network (or computer) can handle them. But the packet loss was not your ISP’s fault.

The Internet uses a system known as “hot potato routing” where a transmitting network hands packets off to a receiving network as soon as possible, which makes receiving networks responsible for most of the packet carriage. So is it reasonable to record packet loss by other networks? The label and the guidelines that come with it do not clarify this issue.

The packet loss is also not its fault if you’re downloading a file and your computer or home network isn’t fast enough to keep up with the sending computer and the ISP’s network. In this case, your ISP will discard packets to your cable modem, DSLAM, or Optical Network Terminator (ONT) when too many packets are queued because your Wi-Fi network or you computer can’t keep up with the sender.

In this case, high packet loss numbers mean the ISP is outperforming your home network, which means it must be pretty darn speedy ISP. I would want that ISP.

The guidelines simply copy-paste the same boilerplate text across both latency and packet loss, as if to admit the authors have no idea what the terms mean. This is sad, but perfectly consistent with the FCC’s desire to turn disclosure into a “USDA Organic” scenario instead of one in which the label imparts useful information.

How to Fix the FCC’s Broken Labels

A labeling program is no way to inform consumers about the relative quality and value of Internet services. ISPs are not selling canned food in supermarkets, they’re selling a service that consists of a number of discrete components that have to be broken out into much more detail than “Typical latency” and “typical packet loss.” In other service industries, suppliers are free to advertise service parameters in any way they want as long as they’re truthful.

So the way to approach this is to require ISPs to document that their service claims are truthful, regardless of what they disclose. If the FCC wants to know something about performance parameters, it should convene a group of technical experts or request an existing one – such as BITAG – to make a recommendation for detailed disclosure terms. This process isn’t going to happen overnight, so it should allow the body sufficient time to make a useful and meaningful study.

Simply aping supermarket disclosures is not a serious attempt to help consumers. In fact, it’s insulting.