Everything You Need to Know about Security

If you want a good grounding in current issues in Internet security, the Symantec Internet Security Threat Report is a good place to start. The most up-to-date edition was published last April, but it’s a great overall introduction to the threat landscape with a number of tips and pointers about what you can do to make your computers and your organization’s networks more secure, even if “your organization” is just your home.

Symantec gathers information about attacks and privacy breaches in the normal course of business, and they’re kind enough to share their insights with us in much the same way Akamai does with its State of the Internet connectivity and security reports. The Symantec report is notable for its breadth and depth, and it’s downright scary. The survey covers mobile threats, web threats, social media and scams, targeted attacks, and the business of malware.

In one respect, it’s hard for technologists not to marvel, in a strictly amoral way, at the ingenuity of Internet criminals. State-sponsored actors created things the highly sophisticated Regin espionage malware tool (page 61):

Regin gave its owners powerful tools for spying on governments, infrastructure operators, businesses, researchers, and private individuals. Attacks on telecom companies appeared to be designed to gain access to calls being routed through their infrastructure. Regin is complex, with five stealth stages of installation. It also has a modular design that allows for different capabilities to be added and removed from the malware. Both multistage loading and modularity have been seen before, but Regin displays a high level of engineering capability and professional development. For example, it has dozens of modules with capabilities such as remote access, screenshot capture, password theft, network traffic monitoring, and deleted file recovery.

So this isn’t just a one-off tool, it’s a toolkit for targeted attacks that’s endlessly expandable and upgradeable.

Internet of Things devices are especially vulnerable to compromise because they’re so simple (page 103):

As consumers buy more smart watches, activity trackers, holographic headsets, and whatever new wearable devices are dreamed up in Silicon Valley and Shenzhen, the need for improved security on these devices will become more pressing. It’s a fast-moving environment where innovation trumps privacy. Short of government regulation, a media-friendly scare story, or greater consumer awareness of the dangers, it is unlikely that security and privacy will get the attention they deserve. The market for Internet of Things–ready devices is growing but is still very fragmented, with a rich diversity in low-cost hardware platforms and operating systems. As market leaders emerge and certain ecosystems grow, the attacks against these devices will undoubtedly escalate, as has already happened with attacks against the Android platform in the mobile arena in recent years.

The Android Marketplace is teeming with malware because it’s relatively unchecked. Symantec estimates that 17 percent of Android apps are nothing more than malware (page 8):

Mobile was also ripe for attack, as many people only associate cyber threats with their PCs and neglect even basic security precautions on their smartphones. In 2014, Symantec found that 17 percent of all Android apps (nearly one million total) were actually malware in disguise.

They also believe that 36 percent of Android apps are inadvertently harmful because of tracking, excessive ads and similar features.

One bright spot from last year’s research was the decline of spam. In another report published last June, Symantec estimated that spam had fallen to less than 50% of total email for the first time since 2003:

There is good news this month on the email-based front of the threat landscape. According to our metrics, the overall spam rate has dropped to 49.7 percent. This is the first time this rate has fallen below 50 percent of email for over a decade. The last time Symantec recorded a similar spam rate was clear back in September of 2003. Phishing rates and email-based malware were also down this month.

The bad news is that spam has risen since then, although it’s still below historic highs.

With the decline of spam, text messaging is picking up the slack as a delivery vehicle for malware, which it generally does by carrying links to malicious web sites:

An important trend in 2014 was the proliferation of scam campaigns. Although this category was not the most prevalent, it certainly was one of the most dangerous threats using SMS messages as its vector of attack. These are targeted campaigns, of a range of scams and frauds, addressed to selected potential victims, mainly scraped off classified ad websites. Scammers send automated inquiries about the advert via SMS. They also offer fictitious items for sale, such as jobs and houses for rent, and interact with potential victims by SMS, and then they switch to email for communication. They typically use fake checks or spoofed payment notifications to make victims ship their items or to take victims’ deposits. Naturally victims never hear back from them.

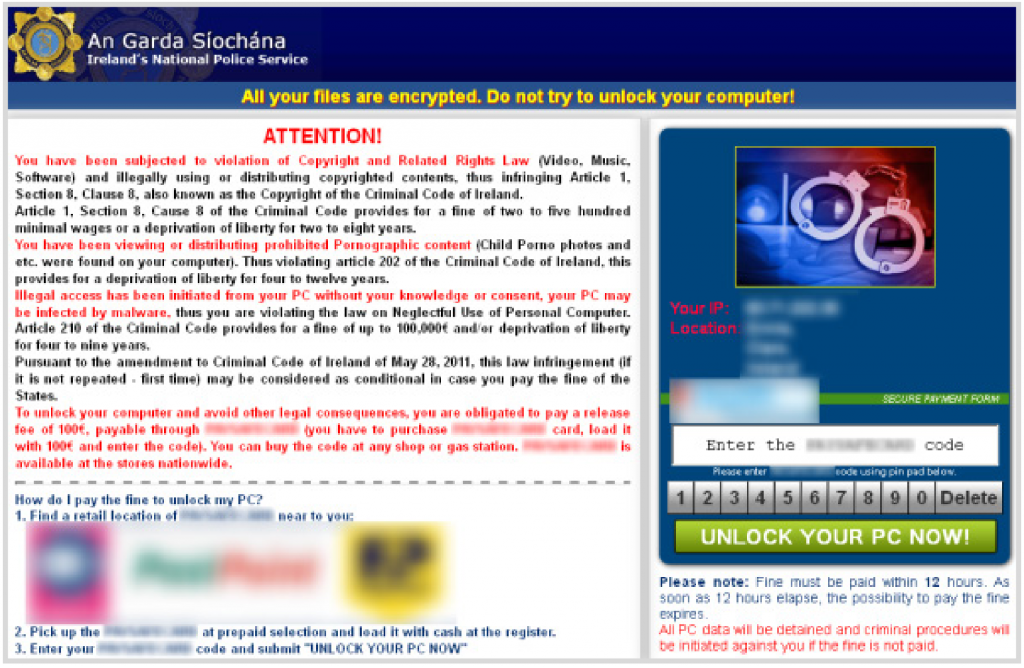

One humorous attack is a kind of “malvertising” directed at users of porn sites known as Browlock (page 43):

Browlock itself is one of the less aggressive variants of ransomware. Rather than malicious code that runs on the victim’s computer, it’s simply a webpage that uses JavaScript tricks to prevent the victim from closing the browser tab. The site determines where the victim is and presents a location-specific webpage, which claims the victim has broken the law by accessing pornography websites and demands that they pay a fine to the local police.

The Browlock attackers appear to be purchasing advertising from legitimate networks to drive traffic to their sites. The advertisement is directed to an adult webpage, which then redirects to the Browlock website. The traffic that the Browlock attackers purchased comes from several sources, but primarily from adult advertising networks.

To escape, victims merely need to close their browser. However, the large financial investment criminals are making to direct traffic to their site suggests people are just paying up instead. Perhaps this is because the victim has clicked on an advert for a pornographic site before ending up on the Browlock webpage: guilt can be a powerful motivator.

Where there’s money to be made, somebody will find a way to make it.

These attacks are essentially impossible to defend against, because like terrorism the bad actors only need to get lucky once while the good guys need to be lucky every single time. So preparing for the inevitability of security breaches with good backups is a prudent plan.