Eric Schmidt’s Spectrum Agenda

Each change in presidential administrations reanimates old, rejected ideas in technology policy. While tech policy was once largely bipartisan, today it’s a bitter battlefield where basic facts are disputed and pathways to common goals are contested.

Case in point is the spectrum allocation policy positions championed by former Google front man Eric Schmidt. During the Obama Administration, Schmidt and his Microsoft counterpart Craig Mundie assembled a cast of semi-technicals – lawyers, policy advocates, public relations experts, investors, and academics – to put their names on a dysfunctional spectrum management plan.

The Schmidt/Mundie plan was issued in 2012 by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology as a Report to the President bearing the ponderous title: “Realizing the Full Potential of Government-Held Spectrum to Spur Economic Growth.” I was not thrilled with the PCAST report at its inception, nor with the 2019 follow up by Schmidt’s minion Milo Medin for the Defense Innovation Board. They haven’t stood up well.

The Dysfunctional PCAST Report

President Obama originally charged PCAST to develop a plan for releasing government spectrum rights to the private sector where they could be used to benefit the public. Instead of delivering such a plan, the PCAST report and its successors produced flimsy excuses for continuing to allow the government – especially the Defense Department – to hamstring wireless innovation by starving the private sector of spectrum rights:

PCAST finds that clearing and reallocation of Federal spectrum is not a sustainable basis for spectrum policy due to the high cost, lengthy time to implement, and disruption to the Federal mission. Further, although some have proclaimed that clearing and reallocation will result in significant net revenue to the government, we do not anticipate that will be the case for Federal spectrum. (PCAST report at vi.)

I addressed the claim that the well established practice of upgrading (or sunsetting) legacy systems to reduce their spectrum footprints and selling off the excess as flexible use licenses was “unsustainable” in a paper on the “upgrade-and-repack” practice I presented at the TPRC conference in 2013. In essence, spectrum rights transfers are as sustainable as is innovation itself. Innovation is where spectrum comes from.

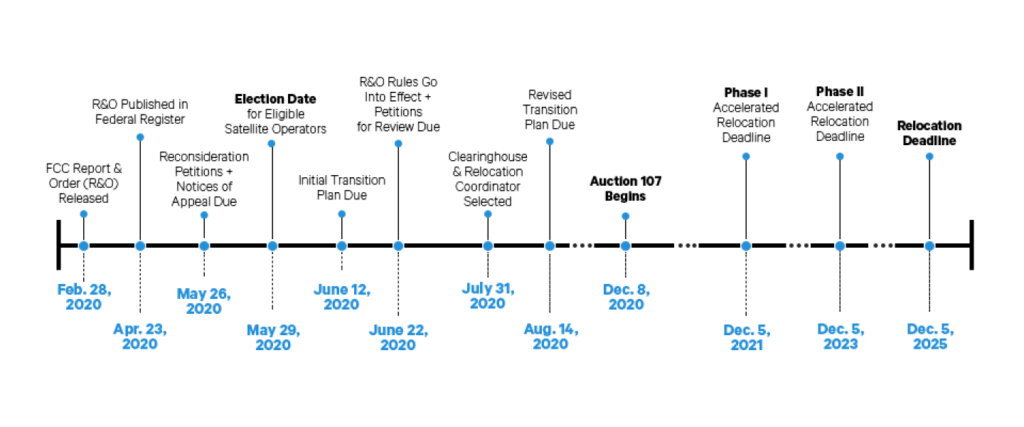

The claim that reassigning spectrum rights takes too long – decades in the PCAST report’s estimation – is contradicted by reality. The first phase of the C-Band reallocation (from GEO satellites to 5G,) took less than two years from FCC Report and Order to deployment.

SES C-Band Timeline

The major stumbling block to C-Band reallocation was the government itself, with FAA raising last minute objections. Meanwhile, the CBRS system based on the PCAST model has proved to be nothing more than a solution in search of a problem.

Dysfunction Loves Dysfunction

While commercial operators regard PCAST sharing as impractical, DoD continues to pretend it’s beautiful. Writing for the Defense Innovation Board on 5G, Google’s Medin parrots his PCAST report’s (he’s a signatory) sustainability (“…status quo of spectrum allocation is unsustainable”) and delay claims:

The average time it takes to “clear” spectrum (relocate existing users and systems to other parts of the spectrum) and then release it to the civil sector, either through auction, direct assignment, or other methods, is typically upwards of ~10 years. (DIB 5G Study at 10.)

We now know this estimate assumes zero cooperation on the part of the vacating party. It’s a question of motivation as the satellite operators were compensated for speedy relocation.

To its credit, the DIB 5G study also pans CBRS:

There is precedent for successful spectrum-sharing – in 2010, the FCC opened up the 3550-3700 MHz bandwidth (known as Citizens Broadband Radio Service, or CBRS) to the commercial sector. However, this process took more than five years, a timeframe that is untenable in the current competitive environment. (DIB 5G Study at 11.)

Medin’s alternative to upgrade-and-repack and CBRS is even worse, however. It wants 5G operators to share a single network:

DoD should encourage other government agencies to incentivize industry to adopt a common 5G network for sub-6 deployment. Incentives can include: accelerated depreciation, tax incentives, low interest loans and government purchase of equipment and services. (DIB 5G Study at 28.)

Medin’s justification – improved security – doesn’t follow from experience. If attackers can focus on a single network, their job becomes much easier than attacking a dozen or so. Redundancy is a key element of reliability.

Inventing New Arguments for Old Ideas

Oblivious to the judgments of history, Schmidt still hawks his spectrum policy pink elephants on the pages of the Wall Street Journal and through venues controlled by his Schmidt Futures investment fund. The only change is the replacement of the discredited PCAST claims of sustainability and delay with even more outlandish claims about performance:

AT&T’s and Verizon’s new 5G networks are often significantly slower than the 4G networks they replace…America’s average 5G mobile internet speed is roughly 75 megabits per second, which is abysmal. In China’s urban centers 5G phones get average speeds of 300 megabits per second.

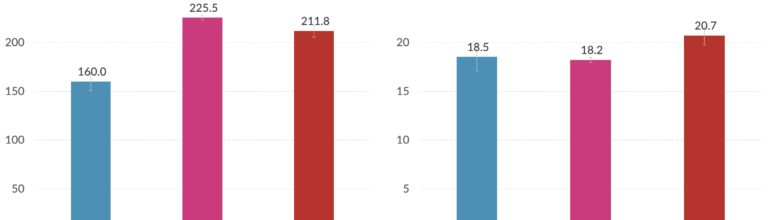

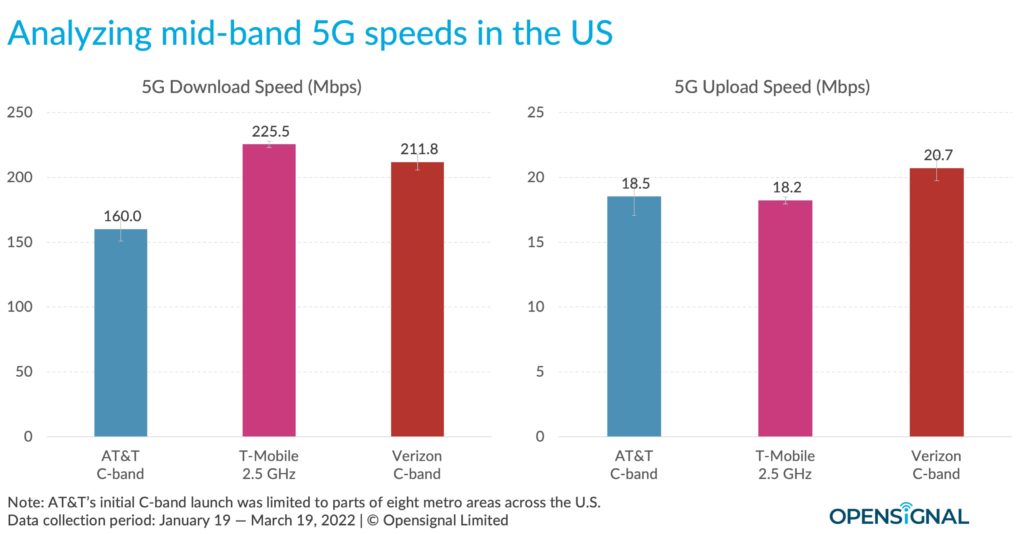

These nonsensical claims aren’t supported by impartial observations. Open Signal says US 5G users see download speeds in the 200 Mbps range. Our coverage is vastly better than China’s; the China card is the last refuge of scoundrels.

Open Signal Midband 5G Assessment

What is Schmidt’s Agenda?

Eric Schmidt and people close to him have been bashing US spectrum policy for ten years. It’s not clear to me why they’re doing this.

Schmidt is not a spectrum engineer, neither schooled nor self-taught. After embracing a whole new architecture for spectrum sharing in the 2012 PCAST report, Schmidt has switched to a “government first” approach that seeks to model the US economy after China.

The PCAST sharing model was never going to work, but Schmidt appears to have backed it with full faith and passion despite a complete lack of evidence. I think we can say the same thing about his current “lets’s be like China” model. China is actually lagging the US on all the important dimensions of 5G deployment.

A Reliable Spectrum Pipeline

The only consistency here is the lack of consistency – and a lack of study. Instead of chasing a series of shiny objects the US needs a predictable and reliable practice for transferring spectrum rights among and between old and new applications.

The US needs to create a system that keeps spectrum licenses in circulation, like dollars in the economy. Every technical system that uses spectrum today will be obsolete some day.

The spectrum pipeline acknowledges that fact and leverages it to make spectrum licenses available to the technical systems of tomorrow. I’ll dig deeper into that subject in forthcoming posts.