An Important Study on the IP Transition

I’d like to recommend Anna-Maria Kovacs’ study on the IP transition, Telecommunications competition: the infrastructure-investment race. It’s the most cogent and thorough analysis of the digital communications landscape in the US I’ve seen in a while, and it fairly oozes with data represented in easily understandable form. Kovacs wrote the report for the Internet Innovation Alliance, a politically moderate think tank/advocacy group that generally argues for pragmatic policies that drive more private investment into advanced networks in particular and the Internet economy generally. Like most think tanks in DC, IIA is industry-funded, but facts are facts regardless of whose interests they serve and this report is well researched.

The data show that telecom regulations force traditional providers of Plain Old Telephone Service (POTS to you and me) to over-invest in legacy networks and under-invest in broadband IP networks. This fact is the essential issue in the IP Transition, and it should be a major concern to anyone who wants better, faster, and cheaper broadband (that’s all of us, right?)

One of the takeaways of the report is that we’re a lot farther along the road to the All Internet Protocol future that is commonly realized. There are two ways to measure progress in this connection:

- How many people rely on POTS as their exclusive mode of communication with the rest of the world?

- What percentage of today’s network traffic is POTS to POTS?

The answers are surprising. Starting with the second, bear in mind that the interconnections between telephone networks already use the same system of IP/MPLS over fiber that the Internet uses. This is to say that there is a single, coherent, global network system that connects not only ISPs but POTS providers, so in the largest sense the transition is already complete. Phone calls between North America and India already move over IP for at least part of the journey. We can thank people like Tom Evslin for this, as his ITXC Corp. proved the utility of routing phone calls over the Internet backbone in the late 90s and ultimately became one of the largest carriers of phone calls on the planet. Kovacs calculates that POTS carriage represents less than 1% of IP traffic today, and is shrinking.

In one sense, this isn’t quite as meaningful as it looks, because video and web traffic can always be counted on to overwhelm narrowband traffic in each minute of use; Netflix streams at a rate of 2.5 Mbps on average (or close to it), 100 times more than POTS with typical compression. Over The Air TV consumes closer to 1000 times as much as classic POTS, so no matter how you measure it, a minute of video takes more bandwidth than a minute of telephone service.

The disparity between the bandwidth needs of video and POTS is not an argument for maintaining dual networks, however, regardless of the commentary by Elise Ackerman and some other gadflies. In fact, it strongly suggests that there is no longer a case for dual networks as the global IP system has the capacity to carry telephone calls in its spare time (as it already has, for the most part.)

The one percent of traffic statistic has a much larger significance, however. More than anything, it tells us that the people have moved on from the POTS norm of narrowband, real-time, person-to-person communication to richer forms of communication and information use. When one percent of telecommunication goes through the legacy mode and 99 percent uses the new broadband modes, legacy mode is clearly a relic that has all but completely been discarded by the vast majority of people the vast majority of the time. Does it make sense to require telcos to spend half their capex and opex on one percent of network usage? Not in any rational economy.

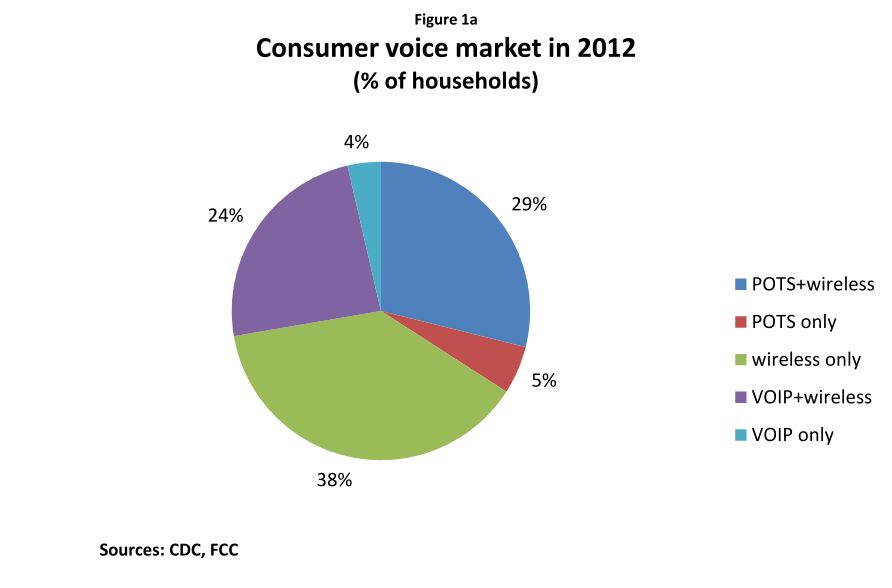

The role of POTS is even smaller than the one percent of network usage number suggests, however. The overall market for voice communication services is actually divvied up among several types of service providers: POTS, VoIP, and mobile, where VoIP includes over-the-top providers such as Vonage as well as the off-to-the-side cable providers who carry voice over different channels than those used for Internet access.

Most households use multiple service providers: 53% use mobile plus POTS or mobile plus VoIP. In addition to the multimode households, 38% use mobile only and four percent use VoIP only, so the portion of American households that rely on POTS as their sole means of electronic communication has now shrunk to five percent.

In all, 34% of US households retain a POTS line, but it’s clear that most don’t use it much; in most cases, it’s probably a security blanket that comes in handy when their cell phone battery is dead, or as a receptacle for telemarketing calls or other forms of unpleasantness. [Note: what people do with their POTS lines is an interesting topic for study.]

While it’s apparent that a key problem with POTS is how to move the five percent to more advanced networks in order to free up investment in the networks that carry 99% of the traffic and serve 95% of the homes, some advocacy groups want to retain the POTS network as long as possible. These tend to be those who’ve argued for strict “net neutrality” principles for IP networks: Free Press, Public Knowledge, and the telecom union, CWA. While this appears to be simply a matter of opposing whatever the traditional enemy wants to do – it’s no secret that AT&T and Verizon want to be freed of their regulatory duties to keep the POTS network alive – it’s actually a bit more.

While POTS is a narrowband application, it’s actually quite troublesome for ISPs because of its stringent timing requirements. It’s not an issue for the Internet’s backbone networks, but network are more variable at the neighborhood level than at the backbone level. Consumer-grade Internet services are heavily shared systems in which Quality of Service – the delay and packet loss that each user experiences – is quite variable. When you’re viewing a web page or a video, these variations aren’t visible. Video streaming goes from a disk on the server end to a buffer on the client end, and this buffer is large enough to absorb variations on delay and loss without affecting the viewing experience.

This isn’t possible for over-the-top VoIP, as those of use who use Vonage and similar services can attest. VoIP can’t be buffered, but it can be protected from delay and packet loss by network management that treats it differently from generic web use. Providing management protection for one application but not for others raises the kinds of issues that net neutrality advocates like to sweep under the rug. The so-called “best efforts Internet” that’s blind to application needs is not as functional as we’d like it to be, and simply throwing bandwidth at the problem doesn’t bridge the gap between VoIP’s needs and capabilities of the “best efforts” service that treats all packets and all applications the same.

So we can’t simply convert POTS to best-efforts IP without sustaining a loss of quality. We have two choices for high-quality voice over IP networks (and this includes HD Voice, which should replace standard VoIP in any case):

- We can route VoIP over a specialized IP network that handles nothing but traffic requiring premium treatment and boost this traffic in the neighborhood; or

- We can provide premium treatment to VoIP over the general purpose Internet and honor this treatment all the way to the end user.

The winning strategy is go with option 2, for reasons of cost and functional richness, but that requires an end to the fantasy that blind treatment of all Internet traffic is preferable to smart, application-aware treatment. This option will ultimately be forced on the Internet by LTE, the latest generation of mobile networking and the first form of mobile broadband built on IP. When mobile voice moves to IP (it uses legacy facilities today), IP Quality of Service will become a necessity.

There are other issues as well, chiefly ones of reliability. Every portion of the POTS network is built to be extremely reliable, as you’d expect from a network that was the only game in town for most of its life. The Internet is built on a completely different philosophy, the assumption that every component is unreliable and the overall system survives failures by switching to redundant facilities when parts of it fail. Overall, redundancy is the superior means of achieving reliability. There have been long discussions on this point for the past 40 years, and the conclusion is clear. [Note: I spent a good part of my engineering career with a company who built its brand on reliability, Tandem Computers, where the redundant components theory was practiced. Tandem computers are more reliable than POTS.]

The Internet is built on packet-switching technology that is intrinsically capable of reliability-by-redundancy, but the Internet itself doesn’t operationalize it. When a link fails inside the Internet’s routing system, manual intervention is often needed to correct the problem. This problem is not universal – most IP networks can automatically reroute internally – but it tends to be a fact of life where networks interconnect with each other. It’s also a solvable problem.

We’re not going to get IP networks that supply power to attached devices like POTS does, however. Achieving reliabililty in the face of power failures will depend on batteries, generators, and Uninterpretable Power Supplies (UPS) as it always has for computers.

There’s also an issue with the use of 911-type services, but it’s largely overblown. The real problem with modernizing 911 is making the service itself capable of interworking with the applications that consumers want, or with distributing a 911 app to smartphones and computers. 911 would become much more valuable if operators would access the video cameras we use for Skype and Hangouts, for example. So the complaining on this front should be directed at the 911 establishment, not at IP networks.

But I digress. Kovacs’ paper is treasure trove of important and useful data documenting how far we are in the migration from POTS to IP. I recommend it to anyone who’s interested in the subject.