Rural Broadband is the FCC’s Top Priority

A New York Times editorial (Expect a Cozy Trump-Telecom Alliance) inadvertently raises questions about the FCC’s role and direction in the Trump Era. The Times is concerned that “a lack of competition for some services [such as cable TV and broadband] is driving up prices.” It then suggests that appointing a new Democratic commissioner with telecom celebrity status will reduce prices, the implied overarching goal of the FCC.

I think this argument is misguided because it misconstrues both the mission of the FCC and the effects of competition on prices.

Celebrity FCC Commissioners

The Times argues that Democrats should not renew the term commissioner-in-limbo Jessica Rosenworcel. Rosenworcel officially leaves the commission just after the first of the year because her reconfirmation was held up by Chairman Wheeler’s refusal to commit to stepping down until time had run out for her confirmation vote.

Oddly, Wheeler denies any recalcitrance on his part, but such a denial is no more credible than his insistence that President Obama had nothing to do with his change of position on the legal basis for the Open Internet regulations: not credible at all.

Instead of the independent Rosenworcel, the Times wants Democrats to nominate a Susan Crawford or a Tim Wu to the open minority party seat. Wu coined the term “network neutrality” and championed an FCC investigation into apps stores for mobile devices. Crawford champions fiber optic cable rollouts to every home and business (at taxpayer expense if necessary) and supports a fairly radical version of net neutrality. The Times says either would use the FCC’s bully pulpit to “speak out forcefully for more competition in the industry and common-sense approaches like net neutrality rules.”

Competition and Prices

The Times argues that price increases for cable and broadband services are driven by lack of competition for data transmission. It offers one nugget covering 1995-2005 from a report on cable prices and another on 25Mbps broadband deployment in support. The cited sources are recently-released FCC documents Report on Cable Industry Prices (2016) and 2016 Broadband Progress Report.

It’s not clear why the Times goes back to the Clinton/Bush 43 era for cable TV pricing data. The ten years in question begin with the rise of satellite networks DISH and DirecTV and end with the advent of cable TV-like services from the former telephone companies. Cable TV prices rose then for the same reason they rise now: more channels are created and bundled in the expanded basic tier and local broadcasters demand higher retransmission consent fees. The FCC report says retrans fees rose by 50% between 2013 and 2014, which can’t have anything to do with the number of cable service providers.

Retransmission Consent Compensation. Source: FCC Report on Cable Industry Prices (2016)

These are basic cable costs, and similar (but more dramatic) patterns exist for the more expensive content in expanded basic. In 1995, expanded basic cost $22.35, but 2015 it was $69.03. That looks like price gouging until we note that the number of channels in the tier went up from 44 in 1995 to 181 channels in 2015. Price per channel actually declined from 60 cents to 47, which probably doesn’t mean much to those of us who only watch six or seven of them.

The Race to the Top

So the result of increased competition for cable TV service was actually more channels and higher overall prices. This suggests that consumers are more interested in rich offerings that include their favorite channels than in low, low monthly prices. Some consumers, anyway; many others have simply stopped subscribing to cable TV because the aggregate price is just too high. In some sense, the cord cutters are victims of competition. But cord cutters have low-priced options now as well, such as DirecTV Now‘s expanded basic equivalent for $35/month.

In any event, competition is not always a race to the bottom. The FCC realizes this in its desire to champion higher-speed broadband service. The agency’s redefinition of the “advanced telecommunications” from 10Mbps to 25Mbps comes from a desire to make service providers upgrade their network speeds.

This is happening where networks already exist: the latest Akamai State of the Internet report says the average broadband connection in the US now exceeds 70Mbps. Since most of these high speeds are in urban areas where there is substantial competition between DSL and cable hybrid copper/fiber networks, it’s doubtful that FCC hectoring has much to do with them.

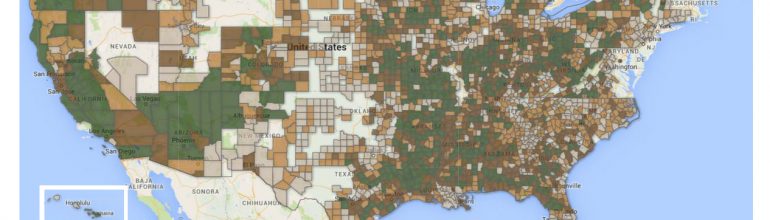

For the same reasons that cable companies cram more channels into expanded basic, they squeeze more bandwidth out of residential Internet connections. Bigger numbers make the service sexier and attract more customers in competitive markets. Meanwhile, there’s very little action at all in rural areas, where 1.4 million households still lack access to 10Mbps service even when satellite options are included (Appendix F.) Effectively, one percent of US households can’t get a 10Mbps broadband connection today.

Foreign Comparisons

We’re often told that the US needs to look to other countries to see how communication policy should look. The problem with doing that, however, is finding other nations with comparable circumstances in terms of geography and population. It’s not entirely meaningful to compare the US to Singapore, a small but densely populated island with the fastest networks in the world. It’s also not fair to compare the US to Canada, an extremely large, sparsely populated nation consisting largely of frozen wasteland.

The UK is a plausible candidate. While more densely populated that the US, it has substantial rural areas, competition between DSL and cable in urban markets, and roughly the same historical level of average broadband speed. It’s also an English-speaking nation with high demand for Internet access and broad proliferation of both full-size and mobile computers.

How Ofcom Does It

UK’s FCC, Ofcom, defines broadband as 10Mbps service. Its annual Connected Nations report highlights homes that can and can’t connect to the Internet at 10Mbps. UK is making progress: between the 2015 and 2016 reporting periods, the broadband coverage gap declined from 8% of households to 5%. This is either better or worse than the US depending on how you value satellite service.

Excluding satellite, 6% of US homes can’t get 10Mbps service (para 79), but including it drops the figure to 1%, as noted. The number of homes that can’t obtain 10Mbps in the US (including the satellite option) and the UK is the same, 1.4 million. Satellite service is harder to use for applications such as voice and gaming, but it’s a damn sight better than nothing.

Hence, it’s reasonable for regulators to focus more on rural broadband improvement than on super-fast urban networks. Urban networks are taking care of themselves thanks to competition between DSL and cable.

It’s also worth noting that Ofcom regards networks with 30Mbps or more as “superfast”, while the FCC regards 25Mbps or faster networks as perfectly ordinary. In Ofcom’s view: “a reasonable online experience requires speeds of at least 10Mbit/s.” In the Netflix/Tom Wheeler view, higher speeds are necessary for 4K video streaming, but it remains a fringe application.

The FCC’s Mission

In the broadband era, the FCC’s job is to see to it that all Americans have access to advanced broadband services. This is spelled out in Section 706 (a) of the Communications Act:

The Commission and each State commission with regulatory jurisdiction over telecommunications services shall encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans (including, in particular, elementary and secondary schools and classrooms) by utilizing, in a manner consistent with the public interest, convenience, and necessity, price cap regulation, regulatory forbearance, measures that promote competition in the local telecommunications market, or other regulating methods that remove barriers to infrastructure investment.

So whatever else the FCC has to do, its first job is to promote investment in broadband networks. Those 1.4 million households who can’t even get satellite out in the boondocks are job one. The FCC can approach the problem in pretty much any way it wants, but it can’t become so deeply enamored with cable TV prices or urban network speeds that it forgets them.

The FCC – thanks to the communications industry – did this job well in 2014 when the number of unserved households fell by 40% in one year. By any measure, this is a “reasonable and timely” rate of progress. Progress in 2015 is hard to assess because the benchmark speed changed, but it could be as high as 60%.

It could also be the case that progress was reversed, because the new benchmark meant that 10 million households served by 10Mbps service became unserved under the 25Mbps standard. The FCC report is deliberately obtuse about the effects its shifting benchmarks (not to mention variations in included technologies) have on timeline analysis. I understand why the agency felt a need to change its standards, but we still need the data that permits us to put each year in context.

What Kind of Commissioners does the FCC Really Need?

A grandstanding celebrity commissioner from the minority party will not help the FCC adopt a more reasonable and thoughtful approach to improving rural broadband. Celebrity at the FCC only produces unfortunate results, as the last three years have shown. And each commissioner only has one vote in any case.

The FCC needs a commissioner with close ties to Capitol Hill who can help the members of her party forge alliances with Republicans to address the rural broadband problem more effectively. Improving the rural economy is in everyone’s interest because that’s where our food comes from. Continued advances in high-tech ag depend to a great extent on connectivity, so rural broadband is more important than idling away the hours watching TV reruns can ever be.

Rural broadband actually matters, even if urban newspapers are too engrossed with perceived needs inside their bubbles to realize it.