Net neutrality advocates discover quality

Barbara van Schewick is a professor at the Stanford Law School and director of the Center for Internet and Society, Larry Lessig’s old job. She is without question the most dedicated advocate for strict net neutrality regulations the world has ever seen. During the runup to the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order she had more than 100 meetings with FCC and Hill staff.

While many OG net neutrality advocates have dropped out of the game in the 21 years since Tim Wu delivered his paper, Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination, at the Colorado University Law School, BVS is still at it. She filed comments and a reply to the current net neutrality rule making in January and visited FCC staff last week to discuss her slide deck about Non-BIAS data services, the area of broadband services exempt from Internet Service Provider net neutrality regulations.

Her January recommendations would effectively erase the NBDS exception, treating all broadband service as access to the Internet even when it has nothing to do with the Internet. The comments are noteworthy because of the breadth of their paranoia, blindness to the engineering realities of today’s Internet, profound ignorance of 5G, and failure to even mention the concept of network quality of service.

Revising her position

The slide deck shows considerable moderation of the hard-edged position BVS laid out in her reply. It grudgingly acknowledges the need for Quality of Service management and considers how it may be allowed without dismantling the entire conceptual basis of net neutrality. While her revised recommendations are considerably more sensible than those in the reply, they still fall short of supporting innovation in network services and applications.

Before we dive in, let’s take a step back and consider what Quality of Service (QoS) is and why it’s important to network applications. Broadband networks have multiple dimensions of quality: capacity, latency (delay), consistency of a latency, and reliability are the most important ones.

Capacity (also known as throughput,) measured in bits per second, determines how long it takes to perform bulk data transfer. This comes into play when transferring files, backing up and restoring storage, watching videos, and many forms of browsing. Net neutrality advocates have generally maintained that it’s the only dimension of network quality that matters.

The more subtle factors

For network applications such as voice, video conferencing, and gaming, interactivity is the primary consideration (after the basic capacity needs of the application are met, of course.) We want to avoid the buffering that takes place when we start watching videos.

One time buffering is not too horrible for the user experience in one-way applications, but buffering of any kind is deadly for interactive ones. If there’s a delay between the action a gamer sees on their screen and their ability to react quickly, they can literally die in the context of the game. So gamers require low latency.

Net neutrality advocates have a history of asserting that latency is simply a matter of capacity, but things don’t work that way on real networks. File transfer consumes all available network resources by design, hence it causes delay for every application sharing the network while the file transfer is running. Since the early days of the Internet, routers gave priority to interactive terminal sessions over file transfers.

Fuzzball cheats gloriously…since 1988

The Fuzzball router created by David Mills in the 1980s is a case in point:

The Internet protocol includes provisions for specifying type of service (TOS), precedence and other information useful to improve performance and system efficiency for various classes of traffic. The TOS specification determines whether the service metric is to be optimized on the basis of delay, throughput or reliability and is ordinarily interpreted as affecting the route selection and queueing discipline. The precedence specification determines the priority level used by the queueing discipline…

As the NSFNET Backbone has reached its capacity, various means have been incorporated to improve interactive service at the possible expense of deferable (file-transfer and mail) service. An experimental priority-queueing discipline has been established based on the precedence specification. Queues are serviced in order of priority, with FIFO service within each priority level. However, many implementations lack the ability to provide meaningful values and insert them in this field. Accordingly, the Fuzzball cheats gloriously by impugning a precedence value of one in case the field is zero and the datagram belongs to a TCP session involving the virtual-terminal TELNET protocol. –

Mills, D. L., “The fuzzball,” ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, Volume 18, Issue 4, pp 115–122, 01 August 1988.

This is not just about price gouging

In the reply, BVS appears to deny the existence of and practice with precedence in the Internet:

The 2015 Open Internet rules ban ISPs from offering technical preferential treatment (so-called “fast lanes”) to providers of Internet applications, content, and services in exchange for a fee.

The ban on charging apps for a fast lane to the ISPs’ customers is a central component of the 2015 Open Internet rules. Allowing ISPs to sidestep this ban would be a fundamental departure from the way the Internet has operated for the past decades.

Lest we jump to the conclusion that BVS is simply concerned with price gouging, note her desire to ban precedence (she calls it “fast lanes”) even as a free service:

The FCC should make it very clear that ISPs can’t try to use the specialized services exemption to give preferential treatment, including via network slices, to select apps or categories of apps, regardless of whether it is charging for the privilege.

Clearly, her concern is not petty economics, it’s the need to preserve the Internet as (she believes) it has always been. A fulsome ban on NBDS (for fee and otherwise,) is about preserving the purity of the Internet.

The flip-flop

The most glaring error in the January reply is the too-narrow formulation of the grounds for offering NBDS:

To close that loophole, the FCC needs to clarify that offering special treatment to content, applications, and services that can typically and objectively function on the open internet constitutes an evasion of the Open Internet rules and is prohibited by the FCC’s rules. By contrast, offering special treatment to content, applications, and services that objectively cannot function on the open internet does not constitute an evasion of the Open Internet rules.

This has never been the consideration for QoS. We manage QoS in order to allow applications to function as well as is reasonably possible. We can say that TELNET “functioned” after a fashion before Fuzzball; it just didn’t function very damn well.

Pssst…listen to this

Binary thinking has long been a feature of net neutrality advocacy in general and the BVS approach in particular. Sometime between January and March, a colleague must have taken her aside and whispered that sometimes precedence is a good thing.

In the slide deck, BVS introduces the notion of “Net neutrality-friendly QoS”.

It has the following characteristics:

- Application-agnostic: available to all apps and classes of apps & no discrimination in the provision of the different types of service

- End user-controlled: end user chooses whether, when, and for which app(s)

-> consistent with the no-throttling rule - End user-paid: only BIAS subscriber is charged (if at all) for use of the different types of service

-> consistent with the no (third party) paid prioritization rule - Protecting the quality of the default BIAS service

Houston, we have problems

This is more like a child’s Christmas wish list than a sensible policy prescription. Points one and four contradict each other: If all classes of apps can choose low latency, we lose the ability to protect moderate data volume apps such as Zoom from interference with high volume disk backups, and along with that we degrade the default QoS.

Point two fails to acknowledge the fact that most end users would prefer to have latency vs. throughput decisions made by another party, such as their operating system vendor or their ISP. Some ten years ago, I asked BVS at TPRC whether users should be allowed to delegate their QoS rights to third parties and she said she needed to think about it. I’m still waiting for her answer.

Point three re-introduces paranoia about price-gouging that she dispatched in the reply. If fast lanes are good, it shouldn’t matter who pays for them; and if they’re bad, economic questions are irrelevant.

Firms who might want to pay for QoS have a number of options to choose from if ISPs are verboten: they can hire CDNs or accelerated video conferencing backbones. They can lease extra backhaul capacity, and they can even build their own networks as the hyperscalers have done.

In an increasingly competitive ISP market, the chief consideration should be who can offer the service at the most appropriate price for the quality and reliability of the service. This list needs work.

Why did this change of heart happen?

I suspect (but cannot prove) that BVS’s about-face came from a realization that the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF, the body that creates Internet standards) has adopted standards meant to improve working latency under load, L4S (Low Latency, Low Loss, Scalable Throughput) and NQB (Non-Queue-Building Per Hop Behavior).

These new standards may be able to significantly lower “working” latency (latency under load) for better real-time traffic performance and to support new AR and VR applications as well as very high quality video conferencing. See Comcast’s Jason Livingood explain them to members of the North American Network Operators Group in February.

This approach works for nearly all ISPs. Another way of improving network QoS for Fixed Wireless operators is 5G Network Slicing.

What is network slicing?

It’s no accident that we’ve had wired broadband longer than wireless. Wireless networks are substantially more complex and sophisticated than wired ones.

Wireless is worth the trouble, however, because it’s substantially more capable. Not only does it support mobility, it makes a broader range of management tools available to the operator. Wireless base stations can be “sectorized” so that a number of wireless frequency channels can be made available in different directions at the same time.

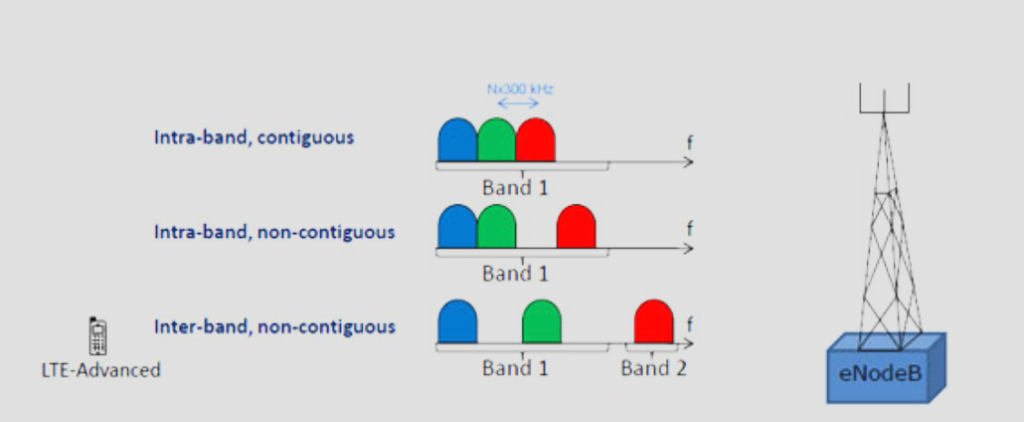

Wireless channels can also be subdivided into subchannels via Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) and Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) in both the downstream and upstream directions. And wireless channels can be aggregated to create new virtual channels out of disparate physical ones via LTE Advanced carrier aggregation or its Wi-Fi equivalent, Multi-Link Operation (MLO).

How can regulators stuff network slicing into their traditional framework?

In combination with OFDMA (the multiple access version of OFDM used by both LTE and Wi-Fi) carriers can use network slicing to create virtual wireless networks that can even be shared by multiple operators. Network slicing can be used to support both Internet and non-Internet applications on single networks and to implement QoS on Internet access networks.

The capabilities of network slicing are frightening to those net neutrality advocates who posses limited technical knowledge. Recall that BVS admits that her primary objective is avoiding “fundamental departure from the way the Internet has operated for the past decades.”

Progress in network engineering necessarily departs from traditional practice. That’s what we do in engineering. So how does net neutrality co-exist with progress?

Loosen the grip

It should not need to be said that regulators should tolerate experimentation with new ways to manage networks better than they were managed “for the past decades,” but this is where we are. The FCC wants to be a cop on the beat constantly on the lookout for bad behavior on the part of ISPs, and a host of non-profits urge it to “ban first and ask questions later.”

Net neutrality advocates are certainly right to insist that ISPs refrain from harmful, anti-competitive practices. Where they go wrong is assuming that every departure from traditional practice is bad. They’re a lot like the anti-vaccine, natural foods, and herbal medicine campaigners who always assume that the past was a golden age where everything was good and nothing was bad.

Having a good heart is a necessary but insufficient qualification for regulating one sixth the national economy; you also need to know what you’re doing, you need to test your assumptions with data, and you need to change course as conditions warrant. Instead of looking to reinforce the status quo, you need to seek ways of improving it.

This is an economic problem

Net neutrality is not as much as engineering problem as an economic one. The high level signals that the Internet is in good shape come from the traditional measures of success in innovation:

- Is the reach of the network increasing?

- Are objective measures of network performance improving?

- Are prices in line with service capabilities?

- Is Consumer Surplus increasing?

- Are new applications emerging?

- Is the Internet’s quality of experience improving?

- Are new entrants taking part in the markets for residential and commercial Internet service?

If the answers to all of these questions are yes, the regulatory status quo is probably working. There is no need for regulators to micromanage traffic management and commercial business practices when the marketplace is healthy.

Net neutrality advocates are embarrassed that the greatest explosion of innovation and competition we’ve ever seen in Internet service has taken place since the passage of the Restoring Internet Freedom Order. It’s a hard pill to swallow, but the FCC and the advocates of strict net neutrality would be wise to accept the victory by confining their regulatory aspirations to the contours of Title I.

OK, but the FCC is REALLY committed to Title II

In the real world, the FCC is still going to regulate the hell out of ISPs. It’s a political agency operating in an election year and some core constituencies expect the Title II hammer to strike this marketplace once again. If all of this is true, the rule on NBDS shouldn’t worry about who pays for QoS as long as baseline, best efforts QoS is good enough for many applications. That’s actually what they do in the UK these days.

We also don’t need to worry about NBDS degrading best efforts QoS. QoS is not a zero-sum game and degradation only comes from sharing a network resource with too many others. And we certainly don’t need to lose sleep over “zero-rating” or applications bundled with free network access.

If the main concern is ensuring that investment in network upgrades isn’t stifled by QoS, that’s easily measured. And if the FCC finds that it’s happening, there are ways to address that problem directly.

An agency what works with Nobel Prize winners can certainly do a better job of ensuring the vibrancy of the broadband market than by copying a California law passed by a term limited legislature with no expert input to speak of. The FCC should reach deep into its pool of institutional expertise and leave the slogans to the pressure groups.