Tim Berners-Lee is Depressed about the Web

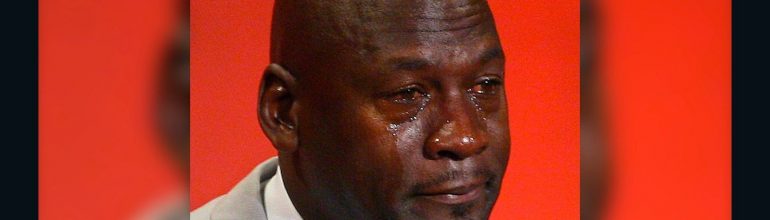

Web inventor Sir Tim Berners-Lee doesn’t like the web any more. As his creation celebrates its 29th birthday, TBL laments its lifestyle choices.

Unlike the happy, carefree, dancing and singing cool kid it once was, today’s web is mean-spirited, overweight, snoopy, and obsessed with money. Hallmark web projects like Wikipedia – all about donating free labor for the benefit of humanity – are unthinkable today.

While the web was once a decentralized, anarchic mess of quirky little sites with dozens (or maybe hundreds if you were lucky) of visitors each day, it’s now a fiefdom. A handful of dominant firms have messed it all up:

The web that many connected to years ago is not what new users will find today. What was once a rich selection of blogs and websites has been compressed under the powerful weight of a few dominant platforms. This concentration of power creates a new set of gatekeepers, allowing a handful of platforms to control which ideas and opinions are seen and shared.

TBL wants those platforms and gatekeepers off his lawn, but they’re not going anywhere. And we wouldn’t like it if they did.

Making Do With Poor Tools

TBL’s web wasn’t complete. The web made it easy for people to create and access small sites (some of which grew into large sites), but in the early days it was missing a lot of vital functionality.

For one thing, it lacked an index; so Google created one that proved to be fairly workable after the efforts by Excite, Yahoo!, and Alta Vista failed. It lacked a conversational space, so Facebook and Twitter created a couple after MySpace and Blogger failed.

And it lacked a financial model, so the leaders in indexing and conversation created surveillance advertising and those with things of value, such as Netflix and Amazon, created a retail space. None of this was malicious; as far as I can tell, each one of these innovators did the best it could with the tools it had to work with. But the web loves a monopoly so they’ve become dominant.

The Web has been Webbed

TBL seems to have forgotten what the web did to the Internet. In essence, the web is an application that rides on the Internet’s pre-existing TCP protocol and applications. It fit into the protocol architecture in the place occupied by Gopher, a tool that allowed users to access indexes and repositories of code and documents.

The web didn’t do anything Gopher didn’t do, but it was unlicensed and free. And once we had a web, we soon forgot about file transfer protocols and remote terminal programs. We even forgot about TCP, relegating it to unglamorous “plumbing”.

TCP had done something like this itself: before TCP, ARPANET used something called NCP that hosted file transfer, email, and remote terminal programs. And ARPANET itself was just a software overlay on AT&T’s digital leased lines.

So we’ve been building this skyscraper for a long time, layering new functionality onto old networks. It was only a matter of time until somebody built entirely new structures on the web that altered its original ways of interaction.

The Fate of Icing

In networking, the component that’s the icing on the cake will one day find another layer has been dropped on it. It then becomes the glue holding layers together and the new thing is the icing. That’s not a bad thing, it’s how progress works.

TBL is particularly bitter about the rise of Facebook and Twitter:

What’s more, the fact that power is concentrated among so few companies has made it possible to weaponise the web at scale. In recent years, we’ve seen conspiracy theories trend on social media platforms, fake Twitter and Facebook accounts stoke social tensions, external actors interfere in elections, and criminals steal troves of personal data.

I agree that conspiracy theories are a big part of social media fare and I don’t like this either. But what does it mean for a firm to “weaponize” the web? Governments have certainly weaponized the web in the sense of making it part of their national defense strategies. They’ve had to do that because it’s a powerful lever.

But all the companies are really doing is trying to make money. To promote the idea that the hundreds of thousands of programmers making web apps are trying to achieve (literal) world domination through like buttons and ad sales is to indulge in conspiracy theory.

Fighting Power with Power

When it comes to solutions for this malaise of the web, TBL has little to offer. On the one hand, he demands more action by government: “A legal or regulatory framework that accounts for social objectives may help ease those tensions.”

But on the other, he invokes the spirit of the late John Perry Barlow, the king of the cyber-libertarians who famously denounced government regulation of the Internet:

Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.

Barlow said, of course, that he never really believed this sentiment; it was actually meant to be a convenient fiction: “I knew it’s also true that a good way to invent the future is to predict it. So I predicted Utopia, hoping to give Liberty a running start before the laws of Moore and Metcalfe delivered up what Ed Snowden now correctly calls ‘turn-key totalitarianism’.”

Let’s Form a Committee to Study the Problem!

TBL’s only concrete suggestion is to assemble a team of experts to devise these new social responsibility regulations: “Let’s assemble the brightest minds from business, technology, government, civil society, the arts and academia to tackle the threats to the web’s future.”

But before we get to that, let’s remind ourselves of the regulatory path that got us here: TBL and many others promoted regulations to protect the Internet’s free and open character. He, like many others, insisted that requiring neutrality from networks would enable creativity to flourish in web-based services.

And now he’s complaining about the predatory nature of these very services because he didn’t understand the inevitability of network monopolies. Perhaps the lesson is that imposing strict order on any one part of the Internet simply moves the spirit of domination to another part. But tech monopolies fade as quickly as they form.

Putting Users in Charge Through Standards

The predators and parasites were made possible by a generous regulatory grant that pushed nearly all the costs of networking to the consumer, leaving consumers with little appetite for paying even more for services. So the advertising model crept into the picture to provide them with free stuff.

The web’s greatest shortcoming, as well the greatest shortcoming of the Internet before the web, is the absence of tools of commerce in the plumbing, such as micro-payments. It also needs to provide each user with a persistent identity – or more, and they don’t need to be real – and a dance card for all the permissions we’ve given for data collectors to record our activities.

It needs to log data collection in a systematic way that’s visible not only to the collector, but also to the donor. Only with something like that can we revoke permission at the fine-grained level that make personal control meaningful.

It’s Not That Hard

This doesn’t have to be mandated and enforced by regulation; all that really needs to be done is for web standards developers to devise these mechanisms. Once they exist, data collectors will find themselves locked out unless they play ball. Or we’ll find that users don’t really care.

In either case, we don’t need straitjackets from top to bottom. We need informed consent and reasonable visibility about the activities to which we’ve really consented.

I would have thought a network engineer would have considered the power of standards before turning to regulators to fix a problem that’s seriously misunderstood. The web didn’t create fake news or conspiracy theories; it just made them easier to find.

Where to Start

And believe it or not, that puts us on a path to remediation that we’ve never had before. We’ve diagnosed the illness and placed the patient under observation. Now all we need is good treatment. But please, keep the government in its place; it’s a guided missile that needs to be used carefully.

So let’s see some standards for micro-payments and data collection consent. If they don’t work, we can form another committee.