28 Years of American Cellular Phone Service

2013 will bring the 30th anniversary of cellular phone network in the United States. This archive video about the launch of the Advanced Mobile Phone Service (AMPS) from the early 1980s on AT&T’s tech channel makes us realize how much we’ve come to take cellular phone service for granted. AMPS was considered the first generation (1G) cellular phone service and it replaced the Improved Mobile Telephone Service (IMTS) system which was considered 0G service.

IMTS used very tall cell towers with powerful 250 watt transmitters on the base station and 25 transmitters on the “mobile” luggable devices, which required very large antennas similar to CB radios to be installed on the cars. The towers covered very large circles with diameters of 50 miles. That far exceeds the range of the modern cell phone, but the superb range was actually its biggest liability. The IMTS system could only serve about a dozen users in a major metropolitan area like New York at a time and users had to wait long periods of time for an open channel.

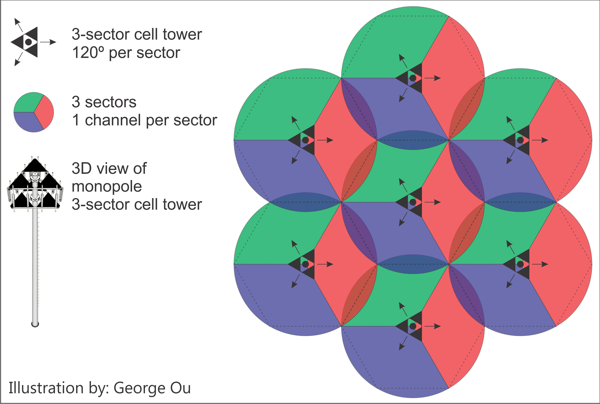

AMPS was the first modern cellular phone system that cut range, and installed array of towers in the innovative honeycomb configuration invented by Rae Young and Philip T. Porter at Bell Labs. This vastly improved caller capacity, albeit at a significantly higher infrastructure and engineering cost than the old broadcast model. See my illustration below for a visual explanation of the modern cellular network.

The AMPS system cut range to increase spectrum reuse. While the number of callers per cell for a given spectrum capacity in an AMPS system was similar to an IMTS system, there were a lot more AMPS cells and each cell reuses all of the available spectrum. The smaller the range, the higher the reuse and the same principle applied to analog or digital communication systems.

This fundamental lesson seems lost on modern day technologists who mistakenly see the superior range of white spaces as an advantage for unlicensed devices, when it can – as seen in the old IMTS system – can often be a disadvantage. On the other end of the spectrum, there are those like the American Television broadcasters (who themselves use some of the least spectrally efficient broadcasting architectures) who argue that Cellular carriers should get all their capacity from more reuse and that they don’t need spectrum. The reality is that the carriers already spend tens of billions of dollars a year upgrading cellular capacity, and it still isn’t enough. Adding spectrum capacity to the existing towers instantly adds more capacity at a fraction of the cost.

In your June 1 piece you describe some “sensible precautions” to reduce cellphone RF exposure. From that angle, should operators put more emphasis on capacity upgrades that reduce RF exposure to users, such as more, smaller cells, and less emphasis on those that don’t, such as adding more spectrum?

What I’ve repeatedly said was that operators should put emphasis on every avenue of adding capacity including more towers (where ever they can avoid zoning restrictions) and getting more capacity. The need for more capacity is so great that every available option must be fully implemented.

Also, when we look at the cell architecture, it’s not easy just to insert one cell tower into a network and still maintain some kind of hexagon configuration. It’s also difficult getting the towers in the exact area that you need one.

I’d also point out that after already spending tens of billions of dollars per year on infrastructure upgrades, a wireless carrier has exhausted their capital expenditure funds. Buying more spectrum has more bang per buck and if spectrum is being wasted (which it is), then it should be reclaimed.

It isn’t fair to demand one industry keep spending more tens of billions to improve capacity while another industry wastes spectrum. And while the broadcast industry can claim they don’t waste spectrum, it has been explained time and time again that they do and any engineer is aware of this.

There are broadcast engineers who don’t think it’s wasted.

I don’t expect those broadcast engineers to say anything different given who employs them. But the undeniable fact is that leaving 1/2 to 2/3 of the spectrum completely unused in most broadcast zones is grossly wasteful.