Global Broadband Woes

The New York Times reports that broadband networks in Germany fail to deliver advertised speeds:

BERLIN — A government study released Thursday supports what many German consumers have long suspected: Internet broadband service is much slower than advertised.

The study by the German telecommunications regulator, the Bundesnetzagentur, measured the Internet connection speeds of 250,000 consumers from June through December last year, making it one of the largest reviews of broadband service anywhere.

The results showed that only 15.7 percent of those using fixed telephone lines and 21 percent using mobile devices achieved the advertised maximum speeds.

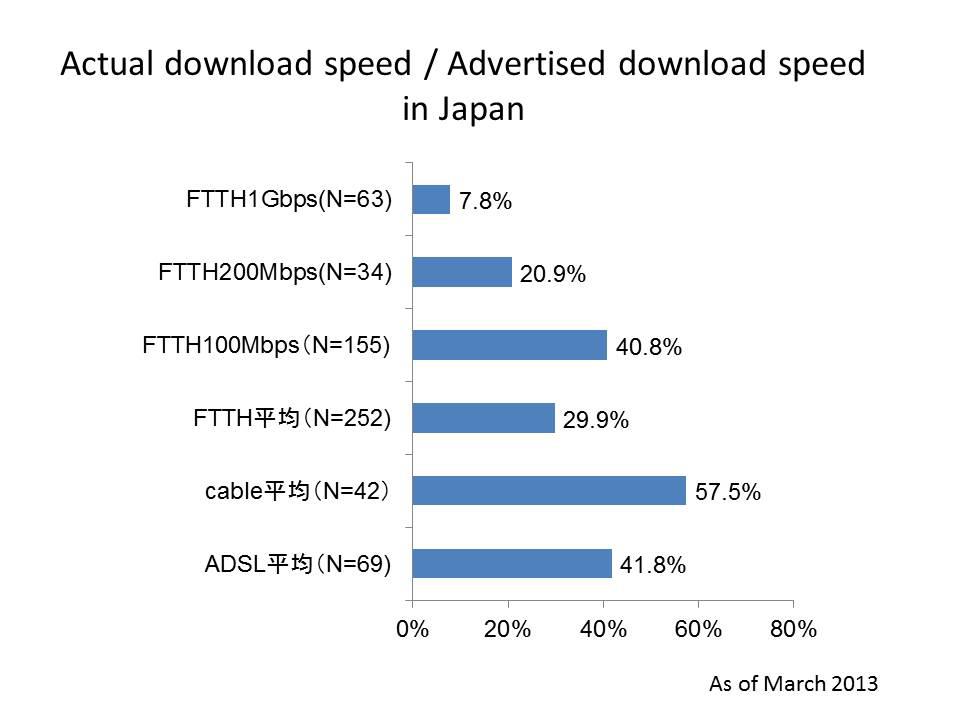

This should be no surprise, as similar testing in other countries shows the same pattern: In the UK, SamKnows found a 50% shortfall, and some recent testing in Japan by academic Toshiya Jitsuzumi finds an even greater shortfall. Here’s Jitsuzumi-san’s findings:

Speed Shortfall in Japan by Advertised Rate. Source: Toshiya Jitsuzumi

The pattern is Germany and Japan is very clear: the higher the promised rate, the less likely the user is to get anything close to it. This situation contrasts sharply with conditions in the US, where we know from the SamKnows testing done for the FCC that advertised speeds and actual ones are closely aligned, especially for more advanced services such as FTTx and DOCSIS 3, and that actual upload speeds exceed advertised speeds for all technologies. In the US, users of the highest speed tiers are likely to get better performance than advertised, as a matter of fact.

Actual vs. Advertised Speeds in the US by Technology. Source: FCC

There are some differences in how this testing is done that may account for the dramatic disparity between the US and other countries, but these differences don’t account for anything like the whole disparity. The testing in Germany and Japan uses Ookla/Netindex test servers, and a test program running on the user’s desktop or laptop computer, while the US testing uses a similar test server against a test program in the user’s Internet gateway. This ensures that slow computers don’t drag down the results and computers on shared Internet connections aren’t impacted by concurrent use.

The differences that shared connections make can be quite dramatic. In Akamai’s testing, the average network capacity of all IP addresses in the US is 29.6 Mbps (Q3, 2012) while the average speed of the same connections when shared in the average way is less than 8 Mbps. The difference in performance is almost entirely caused by concurrent usage. If my connection at home or at the office is capable of 30 Mbps, I only see that when I’m the only one in the home or office who’s hitting the Internet. If a dozen co-workers are downloading files or visiting web sites at the same time, that 30 Mbps is divided among the whole group, hence the reduction in measured speed on each computer is dramatic. So in one instance, we measure the capacity of the pipe and find it’s X, and in another we measure the portion of the pipe that the typical users gets most of the time and find it’s roughly X/4. The network is running at X, but we’re dividing that speed four ways on average.

In the Japanese case, a gigabit pipe slows down to 78 Mbps, which is a pretty ordinary speed for DOCSIS and FTTP and close to the rates that will soon be achievable for FTTC with Vectored DSL. I think we have to conclude that the Japanese people are getting a raw deal from the subsidies they paid to get a nationwide fiber network.