How Not to Measure Internet Speed

Getting up to Speed: Best Practices for Measuring Broadband Performance is a new report from New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute that offers “best practices” for broadband speed measurement. The topic is worthwhile because disclosure of broadband network performance is required by the FCC’s Open Internet Order, and is generally worthwhile regardless of legal mandates.

Unfortunately, the report fails to deliver because the authors – Sarah Morris and Emily Hong – are not well schooled in the Internet’s organization. Broadband measurement is as technical topic, and the development of “best practices” is a super-technical topic that can only be addressed effectively by people who understand the tradeoffs made by various measurement methods. So the report is a failure even though it addresses an important topic. In the following, I’ll highlight the report’s shortcomings and suggest an alternative method of developing best measurement practices. The public interest lobby has a role to play in communicating test results to the public, so I’ll address that as well.

Pricing Problems

The first clue that the report is in trouble is the biographies of the authors; Hong is a recent college grad with a BA in Environmental Studies and a background in studying the digital divide. Morris has been around for a while, and is a J.D. and LL.M. in Space, Cyber and Telecommunications Law from Nebraska Law, where her thesis was on privacy and security concerns related to Smart Grid technology. As far as I can tell, this is the first venture by either into broadband measurement, although Morris has contributed to OTI’s survey of ISP advertisements, The Cost of Connectivity. I’ve criticized that survey for cherry-picking, but it always gets a lot of media play.

Not surprisingly, the new report begins with a few remarks about broadband pricing:

Corresponding to the great leaps in the technology, Americans are also paying more for internet services: the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that the average American household spent $357.80 on internet services in 2014, an increase of 232 percent from the $153.94 spent in 2005...FCC data puts the average annual cost of a standalone broadband in the US at $839.16.

Both the BLS data and the FCC data are suspect. The reference to the BLS data simply says: “Consumer Expenditure Survey 2005-2015, Bureau of Labor Statistics” but there is no ISP data in that survey. I scoured the BLS web site for an hour and didn’t turn up the reported numbers, but I did find that BLS does identify a miscellaneous household expenditure called “Computer Information Services” that could be its source in one of the long raw data files. I don’t think it means what the authors think it means, and I certainly don’t remember a time when ISPs charged users $12.82 a month for a broadband connection.

The “FCC data” is actually Google data used in the Fifth International Data Report: “As discussed more fully below, we used pricing data collected by Google (Google’s data) in this Report” [footnote 2.] Just as the BLS number is too low, the Google number is too high; most consumers pay less than $69.93 per month for wired broadband service. So we’re prepared for a rough ride.

Measurement Problems

The report’s main purpose is to find fault with the FCC’s Measuring Broadband America (MBA) process, which in their view fails to adequately advise lay people of the quality of broadband connections:

By our analysis, MBA itself does not fully achieve best practices for data transparency. We conclude by stressing that the most useful broadband performance data will be data collected from a consistent, reproducible methodology that provides full transparency to those using the data into its underlying assumptions, and in turn, the data’s strengths and limitations.

But the authors don’t understand what MBA measures and why it measures it, nor do they understand the basic organization of the Internet. Hence, it’s bit rash of them to declare MBA a failure from the best practices point of view.

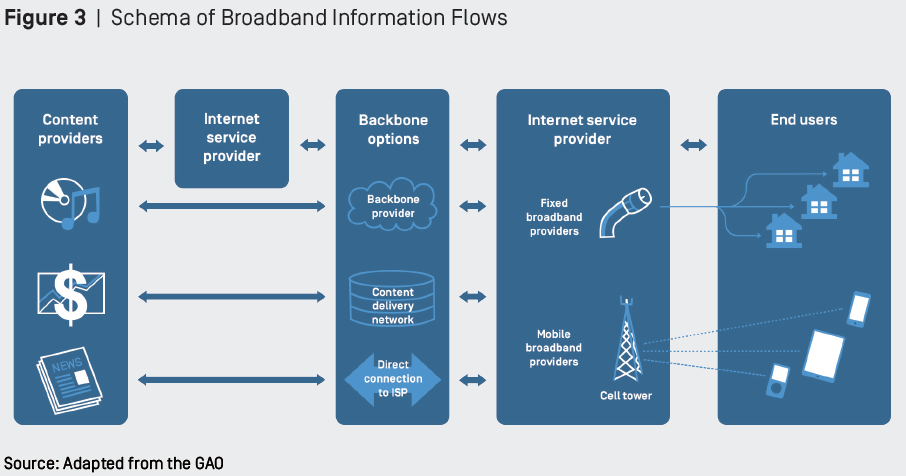

Two issues intertwine when we seek to measure the Internet: raw performance measurements between any two points on the Internet and accountability for performance. The first is important because any speed test can only measure one path, the series of hops or interconnections between the system under test and the measurement server. Every speed test, whether it’s from a dedicated test machine such as MBA’s WhiteBox or Speedtest.net’s web server, measures the path from the test client to the test server. Because the Internet is mesh network of computers, we can’t simply run a test that measures the whole thing.

Because the MBA program is designed to ensure that ISPs are living up to their advertising claims, it can only measure each ISP’s network from the consumer-facing edge to the Internet-facing edge. As the report points out, this approach is not inclusive enough to advise the consumer of the total Internet experience. It was not intended to do that because a complete test from all consumer devices to all Internet services would be extremely cumbersome and would sacrifice the accountability dimension. Google’s web site loads faster than Yahoo’s for reasons that are outside the ISP’s control. Yahoo has chosen not to build the high-performance network of services that Google has built, and that’s not a choice that ISPs are in a position to rectify.

Moreover, measuring the performance of real web sites to real browsers introduces variables on the consumer side that are also outside the ISP’s control, such as fast or slow computers, fast or slow browsers, heavily loaded home networks, and computers with lots of apps running. So the FCC tests from a dedicated test machine – the SamKnows Whitebox – in order to eliminate as many non-ISP variables as possible. The FCC makes raw data available for analysis, not something the consumer cares to do but something public interest groups can do if they want to help consumers understand what they’re buying.

OTI Fails at Internet 101

The report touts the test methodology of OTI’s M-Lab servers without displaying any understanding of the reason that Ookla Speedtest.net takes a different approach:

M-Lab’s NDT test attempts to transfer as much data as possible over a single connection to a server in order to measure performance. The Ookla Speed Test takes a “multi-threaded” approach, using up to 16 streams. There is no right or wrong test configuration, but depending on the configuration the test provides a different performance perspective to the user.

Web browsers use 8 – 16 streams at the same time, so Ookla works the way it does to better approximate the web experience. So if your goal is to measure the web experience, as Ookla does, there is in fact a “right way” to do it.

The most severe shortcoming of the OTI report is the failure of the authors to comprehend the Internet’s organization:

In order to get to your personal device, internet content traverses a segmented route that encompasses a variety of networks often owned and managed by different entities. For example, data that originates with a content provider (like, a server owned by a video streaming service), may first travel through a service provider to another provider providing an internet backbone service (transit), and then through a consumer broadband provider to arrive at your smartphone or laptop (Fig. 3).

While this is a fairly common textbook description of the Internet, it’s not really the way it works most of the time. A large content site like Netflix connects directly to all the large ISPs without any intermediate backbone or service providers. An intermediate size content site, such as the New York Times, is hosted by a public content delivery network (CDN) such as Akamai which also connects directly to your ISP. Hence, the “segmented route” simply doesn’t exist except when you’re accessing content on a very low-volume site that’s probably not capable of stressing your ISP to begin with.

How to Measure Correctly

So the best way to measure the performance between your computer and Netflix or Akamai is with a test server attached to the same Ethernet switch that Netflix, Akamai, and your ISP are using for their interconnection. That’s pretty much what Speedtest and MBA do. And they run their tests the same way a browser works, with multiple streams at the same time. So this complaint isn’t valid:

Thus, interconnection measurement must measure the full path, and not simply the performance between interconnecting border routers, if it is to claim to be representative of the consumer experience.

…because the border most typically is the full path and the SamKnows method runs tests at random times that capture variations in network conditions where they matter.

The report goes back into history in an attempt to justify the M-Lab approach:

Netflix, an internet content provider that has previously complained to the FCC about interconnection issues with ISPs, stated that “meaningful disclosure and assessment of network performance and the user experience should include information on performance to servers and other endpoints located across interconnection points.”

But as Dan Rayburn explained, the Netflix ISP congestion issue was a symptom of Netflix’s transition from CDN user to CDN owner. The issue in question was ultimately traced to Cogent, a transit supplier who oversold its capacity and slowed down Netflix streams in order to satisfy its other customers. Netflix solved this problem by dumping Cogent and negotiating its own interconnection agreements with ISPs. Because the Internet is about direct connections, not segmented routes.

Not Best Practices

So here’s the full list of OTI’s best practices:

1. Data should be collected using a consistent and reproducible methodology.

2. Measurement methodology should accurately reflect the experience of the end user, and uphold standards of transparency and openness by providing precise specifications for measurement and analysis.

a. Measurement should capture performance over interconnection points and at peak hours,

b. Methodology should allow for third-party oversight and verification,

c. All methodological and analytic choices should be available in full transparency,

d. Open software measurement clients and back end (the measurement application) should be open source, and

e. Methodology in analysis and processing of the data should be open.

3. Standardized disclosure formats should include baseline best practices for broadband measurement so that customers can confidently gauge their own connectivity against what is expected and what others receive.

For the most part, these practices are neither desirable nor achievable. While the methodologies may be consistent, that doesn’t mean that any sample is reproducible because the conditions that are measured at time “t” may not recur. Measurement that captures the end user experience is nice to have, but it’s fuzzy from the standpoint of accountability. Measurements at either side of an interconnection points are equally valid, and they should be taken at all hours of the day and night, as they are. The closest we’re going to get to third party oversight is anonymized data dumps, which we have.

I don’t know what “All methodological and analytic choices should be available in full transparency” means, but it doesn’t sound right. Any measurement system makes choices and all we can ask is that we know how it works. Open source is fine, as long as there’s no proprietary information involved. Unfortunately, SamKnows does have some secret sauce, but as long as their system is consistent, I don’t see a reason for not using it. 2(e) is fine, and that’s the norm today.

On the data formats issue, it appear that OTI is undercutting its own usefulness. The average consumer doesn’t care about data formats, only the analyst does. So why doesn’t OTI simply examine the raw data and issue their own analysis? Oh, they do.

So there is very little to these “best practices” but an insistence by OTI that the FCC should use OTI’s test system instead of the FCC’s MBA platform because OTI says so. This would be a mistake for all the reasons I’ve provided.

Immersive and takes on account the variables that affect the speed pricing from tier 1 providers to resellers. Actual internet speed is really a technical topic and what we see on the speed tests are aggregated and simplified results.

Great post! Can you expand on this point:

“Two issues intertwine when we seek to measure the Internet: raw

performance measurements between any two points on the Internet and

accountability for performance.”

Thanks!

Sure. We can measure the load time of a web page on every browser, but we don’t know how much of the delay is caused by the ISP, how much is caused by the web server, and how much is caused by other factors such as the browser, the computer the browser is running on, the home network (including Wi-Fi) and more obscure things such as process and data flows taking place on shared network segments by other people. So we have to construct different tests to isolate all those potential causes of delay, and that can be incredibly difficult.

That makes sense. I misunderstood the original sentence. I thought “accountability for performance” was referring to some kind of method whereby customers can hold an ISP accountable for not delivering the kind of performance that was purchased. Thank you for the clarification!

Holding ISPs accountable for living up to their advertising claims is the intent of the FCC’s Measuring Broadband America program. Unfortunately, consumers still don’t know who to call when a particular web page is slow to load or when it won’t load at all.

So who do consumers call when a page is slow to load or when it won’t load at all? I am a last mile customer in a not quite rural area. My only option for Broadband is Verizon LTE. I am fortunate to be grandfathered into an unlimited plan from a couple of years ago. Often my access is less than .5mb/s or completely drops requiring a reset of the LTE router.

When I can’t load a page I first try to load other pages to see how widespread the problem is. If I can’t load several different pages, I call the ISP or write a complaint on their support site. If the outage is limited to one page, I contact the page owner. Last time I did this the problem turned out to a bad firewall setup at the web site that blocked requests from certain parts of the country due to a lack of communication with CloudFlare. The modern web is fairly complicated and firms with weak technical staffs can’t always get it to work for them.