False Premises: FCC’s Fact-Free Sheet

In the absence of economic analysis for its most aggressive initiatives, the FCC relies on “fact sheets” to justify its decisions. As these fact sheets are actually short on facts, it appears they’re meant to supply supporters with talking points. One recent example is the FCC fact sheet for for its controversial set top box proposal. Every major assertion in this document is either trivial or false, hence it’s reasonable to characterize it as a fact-free sheet.

The very first paragraph alone contains multiple factual errors, and all it tries to do is lay out the predicates for the agency’s proposed plan.

Factual Error 1: No Meaningful Alternatives

FCC “fact sheet” says: Ninety-nine percent of pay-TV subscribers currently rent set-top boxes because there aren’t meaningful alternatives.

TiVo, Hauppauge, and SiliconDust all manufacture and sell perfectly viable alternatives to cable company set top boxes (STB) and digital video recorders (DVR). [Edit: TiVo alone has more than 6 million subscribers, which represents about 5% of US households. Hauppauge has an estimated worldwide customer base of 10 million users, but it’s unclear how many are in the US. In any case, the 99% claim is grossly inaccurate on its face; the correct figure is probably less than 90%.]

The TiVo Bolt is a cable card DVR that provides access universal search across linear TV and video streaming services. Bolt users can watch cable company programming as well as Netflix, Amazon Prime, HULU, Vudu, YouTube, HBO Go, MLB TV, and Pandora. TiVo’s access to cable company content includes both on-demand and ordinary “linear” programming. TiVo has a commercial skip feature for non-sports programming that allows users to, you guessed it, skip all commercials on recorded programming with one button click.

TiVo includes Tribune Media’s Gracenote program guide service for linear TV, the same service used by cable companies, Apple, Amazon, and Roku for the programming they provide. TiVo streams and records programming to portable devices for use outside the home. I personally use a TiVo Roamio (the predecessor to the Bolt) to download TV shows and movies to an iPad for viewing on airplanes and to stream live programming outside the home.

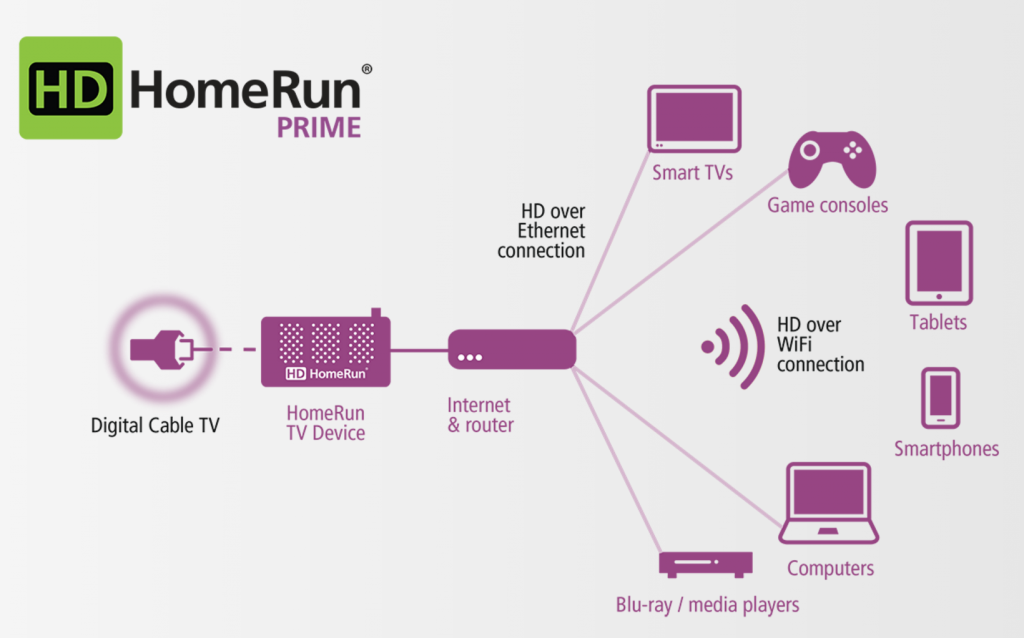

SiliconDust provides cable card devices such as HD HomeRun Prime that attach to users’ local area networks to decode and stream linear TV to applications running on a variety of devices: Apple and Microsoft Windows computers, Apple and Android portable devices, game controllers, and the Amazon Fire among others. For users with Windows versions before Windows 10, SiliconDust streams can be recorded and viewed with Windows Media Center (WMC). Silicon Dust is developing apps that will replace WMC when they’re done. The company’s apps include simple viewers as well as DVR apps that work with a program guide.

Hauppauge offers a slew of TV tuners, cable card decoders, recorders, and viewing apps for PCs, portable devices, and gaming consoles. As the company describes its mobile apps:

Watch live TV on your iPad, iPhone, Android, PC or Mac! Broadway and WinTV Extend send live TV over Wi-Fi at home, or the Internet around the world! Broadway is an always on, standalone TV receiver while WinTV-Extend runs on a PC.

So the reality is that consumers do have meaningful alternatives to cable company set top boxes. All of these devices do at least as much as a cable company STB or DVR does, without any rental fees. The fact that consumers have not flocked to these alternatives does not mean they don’t exist. In fact, the use of these devices has enabled me to watch TV for the past 15 years without a cable company box in my home.

Today, Comcast announced that its X1 DVR is testing an app that provides its users access to Netflix. TiVo, SiliconDust, and Hauppauge already have Netflix apps; TiVo’s is built-in, and the others have clients for platforms that provide Netflix apps. So the people who insist on renting cable company DVRs and STBs do so out of choice, not from necessity. [Note: Whether 99% choose to rent rather than also appears dubious, but I don’t have data for it.]

Factual Error 2: $231 in annual rental fees for STBs

FCC “fact sheet” says: Lack of competition has meant few choices and high prices for consumers – $231 in rental fees annually for the average American household.

The $231/year figure is a completely bogus fabrication that the FCC is mindlessly parroting. Economist George Ford has looked at the data upon which the claim is made and found it tells a very different story:

“Most importantly, across all 10 providers in the survey, the average annual fees paid for all boxes in the subscriber’s home is $145,” Ford wrote. “The average monthly cost per box is $5.15. These averages are well below those reported by Blumenthal and Markey ($7.43 per box and $231 per year). Blumenthal and Markey, grossly overstate — by 60 percent — the fees related to set-top boxes.”

The claim that consumers pay an average of $231 per year comes from a survey of major MVPDs conducted by two senators, but it’s not the answer to any specific question. Rather than ask for this figure, the senators took the average rental fee for boxes that have fees and multiplied it by the number of total boxes per home, for fee and for free. But this calculation omits the free boxes that often come with cable TV plans. AT&T, for example, provides customers with a free DVR and rents additional STBs for $8/month. If AT&T customers have 1.5 additional boxes, they would pay $12/month. But Senate math says the average rental fee is $8/month, the average customer has 2.5 boxes, so the fee is $20/month. Nice.

For Comcast, people like me who use CableCard devices get their CableCards for free. I don’t know how much Comcast charges for non-CableCard devices because I don’t use one and they didn’t publicly disclose it to the senators.

Factual Error 3: $20 Billion in Annual Rental Fees

FCC “fact sheet” says: Altogether, U.S. consumers spend $20 billion a year to lease these devices.

This claim follows from the previous one, and is 60% higher than the reality. The FCC proposal won’t reduce rental fees for STBs.

The fact sheet goes on to make a number of improbable or unimportant promises that indicate, at best, ignorance of the current state of the video player market.

False Promise 1: Access to more devices

The fact sheet promises: Unlocking the box: Free apps will give consumers choice to access content on a variety of devices

Linear TV is already available from third party CableCard devices to a variety of devices including desktop and laptop PCs running Windows, OS X, and Linux; virtually all mobile platforms running Android and iOS; Xbox and PlayStation gaming consoles; video service devices such as Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku; and smart TVs. In fact, it’s pretty much universal, so the FCC’s promise of “more devices” can only mean one thing: new devices will be created that aren’t supported by TiVo, Hauppauge and SiliconDust. This might happen, but it’s not exactly a slam dunk.

The more likely result is a pull-back from the current set of devices supported by CableCard and a diminution of innovation in TV viewing devices. That would be a likely consequence of a the FCC’s planned invasion of a marketplace that’s already quite innovative and is, in fact, offering consumers more than they’re interested in buying already.

False Promise 2: Integrated Search

The fact sheet promises: Integrated Search: Consumers will be able to search across all pay-TV content

But we already have this too. TiVo’s search function covers the cable company, Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, YouTube, and Vudu. It allow the user to instruct the machine to record a program or movie any time it’s shown, and tells the user if it’s already available in streaming form – either free or for a fee – from any of the supported services. So what is this “universal search” going to accomplish that we don’t already have?

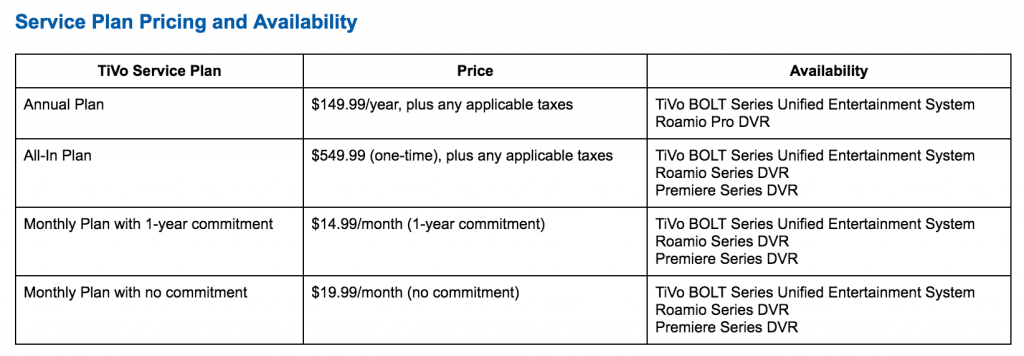

Only one new thing is plausible: Integrated search will be free to consumers (from some companies) in return for ads based on our viewing habits. Integrated search today requires users to pay a fee for access to the linear TV program guide that makes it possible. In TiVo’s case, this fee is typically $15/month, $15o/year, or $550 for the life of the machine.

SiliconDust has a similar fee, currently $60/year for an early adopter version that’s pretty rough but basically functional. The SiliconDust DVR is a Kickstarter project, and it doesn’t get any more innovative than that.

These firms charge a recurring fee for their guide-based services because they pay Gracenote for the data required to make them work. The FCC proposes to make the cable companies give this data to Apple, Amazon, Google, and Roku for free, but that’s going to be copyright problem. The data, you see, doesn’t belong to the cable companies. They actually pay Gracenote for it just as the DVRs do because they have no control over the programmers’ schedules. Comcast, for example, simply opens a pipe to HBO, ESPN, and CBS and delivers whatever content the networks put in that pipe, filling in predetermined slots with local ads. Any advance notice the MVPD gets from the network is not sufficient to build a searchable program guide without the Gracenote data.

So this apparently free program guide the FCC is demanding will continue to be provided by Gracenote with fees passed onto the cable company instead of the DVR company.

Oddly, the FCC doesn’t promise me that my TiVo service will get cheaper with this free program guide, but I can predict that cable TV service will get more expensive as I pay for for this new, free search service that is neither new nor free.

False Promise 3: Copyright Fully Respected

The fact sheet promises: Protecting Copyrights & Contracts: Honoring the sanctity of contracts through pay-TV control of the app and related software

As the integrated search promise shows, the FCC can’t provide the free services it wants to provide without altering existing contracts. If the FCC regulation requires cable companies to give the Gracenote data away for free, their contracts with Gracenote will need to change. So the FCC wants to make itself the overseer of contracts between TV producers and distributors. People who understand the law better than I do say the FCC does not have any legal authority for taking on this role.

The FCC’s presumption that it can do anything it wants to the cable TV business is the main reason Congressional Democrats have joined Republicans in opposing the STB plan. That’s a rare thing in these partisan times, but it’s real.

False Promise 4: Removing Barriers to Innovation

The fact sheet promises: Technology-Neutral Standards: Removing barriers to innovation, speeding products to market

If you read “technology neutral standards” and then move on, you miss the promise. That’s all fine, but the issue comes about with the second part. The FCC proposes to force cable companies to develop apps on “all widely deployed platforms, such as Roku, Apple iOS, Windows and Android”. So picture yourself as the founder of great new startup that’s dead set on revolutionizing the nature of video entertainment. You’ve got your core team assembled, you’ve graduated from your incubator, got your investors lined up, and now you have to build your beta. Are you a “widely-deployed platform?” No, you’re not, so the cable company isn’t going to write an app for you.

If you’re using Android, you’re probably good to go, but what if you want to do something truly innovative? Tough luck, Charley, you better go on bended knee to several cable companies and see if they’re willing to help you. Which is, of course, exactly where TiVo, Hauppauge, and SiliconDust are today.

The FCC plan will not remove barriers to innovation and it will certainly not speed products to market. The only way you do these things is to enable the innovators to work with the programmers and distributors more effectively, which is not the FCC’s job. And even if it were, it’s not in the FCC’s skill set.

False Promise 5: Protection from the Wolves

Finally, the fact sheet promises: Consumer Protection: Emergency alerts, privacy and accessibility

Emergency alerts are the single most annoying feature of TiVo use, for no particular fault of TiVo. Some stations run a crawl with some beeps without interrupting the program you’re watching, but other stations (like my local PBS) actually halt the program and announce the condition over a blue screen with some crazy fonts resembling a 1984 personal computer. So picture yourself watching a football game where it’s the final series of downs with the score tied only to be jerked away from the action by a screen telling you there’s a rainstorm four counties away that might make for some flash flooding. You can’t get back to your game until this is finished. Twice. That’s not what I want.

The FCC’s promises about privacy and accessibility are simply hollow. The apparent reason for this exercise is to make it practical for certain companies that, ahem, offer “free” search services to extend their reach from the Internet into the realm of television viewing. Given that the FCC is doing this to provide such firms the means to combine what they know about my web activity with my TV viewing history, color me skeptical about the claim to more privacy. I don’t particularly care whether Google has this information or not, but privacy hawks certainly do and their opinions are as good as mine.

Conclusion: The Fact Sheet is Fact-Free

So-called “fact sheets” are a staple of advocacy and public relations. This one is only two and a half pages long, yet it’s riddled with factual errors. It’s simply bizarre that the FCC can’t make a case for its so-called set top box order without deviating so radically from easily-proved facts. It’s annoying to see advocacy groups like Public Knowledge making up “facts” to support their agendas, but it’s unacceptable for regulatory agencies to behave this way.

Tom Wheeler’s set top box initiative is not ready for prime time.