Does Fact Checking Work on Fake News?

Facebook is in trouble again thanks to revelations that it has shared personal data with 150 Silicon Valley partners in violation of its promises and contrary to its consent decree with the FTC. The consequences of this deception are going to be severe. But that’s not the topic for today, fake news is.

Researchers are finding that Facebook’s efforts to limit user engagement with fake news are succeeding. The company cites three studies that show 50% reductions in likes, shares, and comments on fake news since 2016.

- Alcott, Gentzkow and Yu published a study on misinformation on Facebook and Twitter showing that interactions with a selected group of false news sites declined by more than half after the 2016 election.

- A University of Michigan study on misinformation compiled a list of fake news sites according to two external indexes, Media Bias/Fact Check and Open Sources. They created a metric, the Iffy Quotient, to measure interactions with fake news; it shows 50% less fake news interactions on Facebook than on Twitter.

- Les Décodeurs, the fact-checking arm of the French newspaper Le Monde, released research that analyzed social media engagement from Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Reddit on 630 French websites. They found that French Facebook user engagement with “unreliable or dubious sites” is now half what it was in 2015.

The Facebook emphasis on reducing interaction appears to be working, but we should bear in mind that the site still has a very long way to go. Absent omniscience, there will always be fake news on social media sites.

So What Can be Done to Combat Fake News?

Fact-checking is the cornerstone strategy for combatting fake news. Platforms that value free speech and real-time interaction have to be permissive, only addressing fake news after the fact.

But fact-checking has issues. It has to reach the audience that has seen the original fake story, and it doesn’t always to this. It also has to persuade people that they’ve been misled, which is hard to do.

As Mark Twain actually said, “How easy it is to make people believe a lie, and how hard it is to undo that work again!” Fact-checking also has two unpleasant side effects: some people respond to criticisms of cherished beliefs by doubling down on erroneous beliefs, the so-called “backfire (or backlash or boomerang) effect.” Others accept fact checks but don’t change their behavior.

The Backfire Effect is Elusive and Contingent

The backfire effect was introduced to the discussion of online fact-checking in 2006 by Nyhan and Reifler. Their research consisted of a survey on the presence of WMDs in Iraq, tax cuts, and stem cell research.

They found that “corrections frequently fail to reduce misperceptions among the targeted ideological group.” They also documented “several instances of a “backfire effect” in which corrections actually increase misperceptions among the group in question.”

While it’s true that corrections often fail to change behavior, subsequent studies have failed to find a robust backfire effect. A 2017 study of vaccine information by Kathryn Haglin, “The limitations of the backfire effect”, is one example.

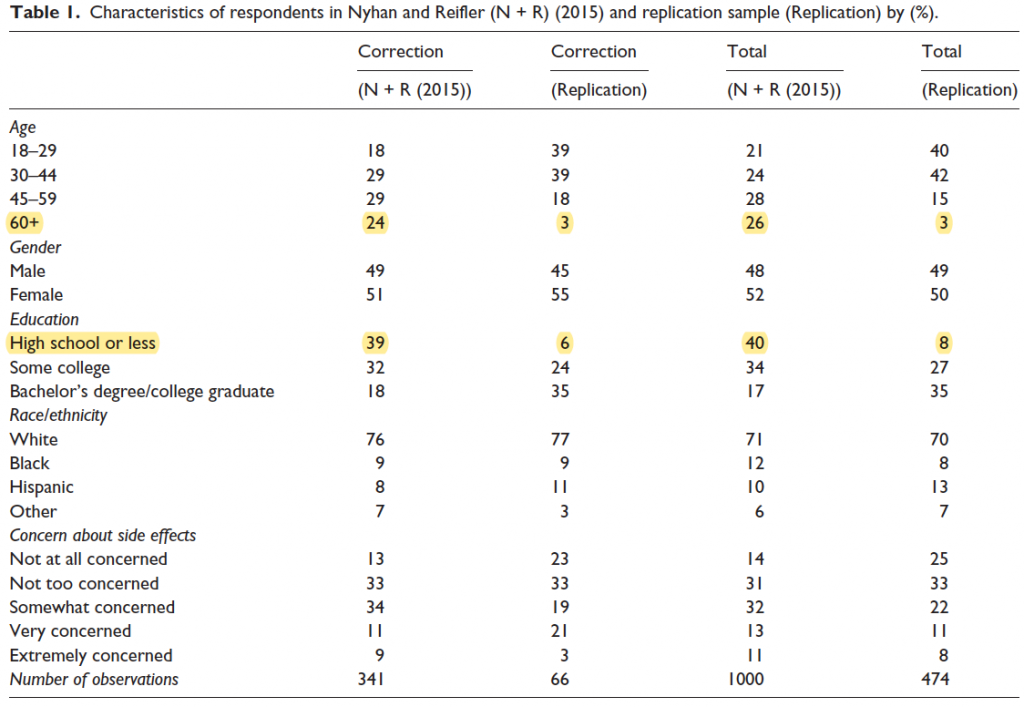

Haglin tried to replicate a flu vaccine study by Nyhan and Reifler (“Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information”) with a different demographic accessed through Google’s Mechanical Turk platform. She found that older people and uneducated people were significantly less receptive to correction than others.

While Haglin is often taken as a refutation of the backfire effect, it’s probably more instructive to consider it a sharpening: the backfire effect depends on the group characteristics and probably also on the way the correction is delivered.

Subsequent research is mixed on the prevalence of the backfire effect. Thomas Wood and Ethan Porter tested 10,100 subjects on 52 issues of potential backfire in “The elusive backfire effect: mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence” and failed to find any backfire. Nyhan is now working with them, which is good.

Some People Just Don’t Care About Truthfulness

Research by Barrera, Guriev, Henry, and Zhuravskaya (“Facts, Alternative Facts, and Fact Checking in Times of Post-Truth Politics”) makes two disturbing findings. For many people, learning that a political figure has spread false information doesn’t reduce support.

For others, simply mentioning false claims changes voting preferences whether corrected or not. They questioned French voters on claims about immigration made by nativist candidate Marine Le Pen.

This was a careful study:

The participants were randomly allocated to four equally sized groups: (i) control group, (ii) alternative facts group, (iii) real facts group, and (iv) fact checking group. The participants in different groups were asked to read different messages. The control group was presented with no information. Participants in the group “Alt-Facts” (for alternative facts) were asked to read several statements by Marine Le Pen (MLP) on immigration, each containing factually incorrect or misleading information, used as part of a logical argument. Participants in group “Facts” were asked to read a short text containing facts from official sources on the same issues. Participants of the group “Fact Check” were provided first with the same quotes from MLP and then the same text with facts from official sources.

Sadly, exposure to facts increased overall support for MLP in both the fact-check and the control groups:

Better knowledge of those subjected to real facts—either through fact checking or through exposure to facts alone—does not however translate into anti-MLP policy preferences and voting intentions. We find that political statements based on alternative facts are highly persuasive and fact checking is ineffective in undoing their effect on voting: being exposed to MLP’s rhetoric significantly increases voting intentions in favor of MLP by 7 percentage points, irrespective of whether they are or are not accompanied by fact checking. Furthermore, in line with the prediction based on the importance of salience, we also find that the voters that are exposed to facts without MLP’s statements are 4 percentage points more likely to vote for Marine Le Pen compared to the control group.

Perhaps this effect is limited to time, place, and subject, but it suggests that letting sleeping dogs lie is the best approach for advocates of liberal immigration policy.

What Have We Learned About Fake News?

All of this suggests that the Facebook approach of limiting exposure to fake news is the best one for political issues. Once people have formed opinions about political figures, fact-checking alone will not change their minds.

Fact checking does have constructive impact on knowledge of truthful information, so it’s not a lost cause. It’s entirely possible that fact checking immunizes against being taken in by false claims in the future even if it doesn’t immediately change our behavior.

Some subjects are so emotional that simply raising them, truthfully or not, tends to influence is in the direction of figures that stake out extreme positions. Remaining silent on all matters of great public concern doesn’t feel like a winning strategy, however.

As with so many newly-discovered social problems, we need more research on the long term effects of fact checking.