My Privacy Taxonomy

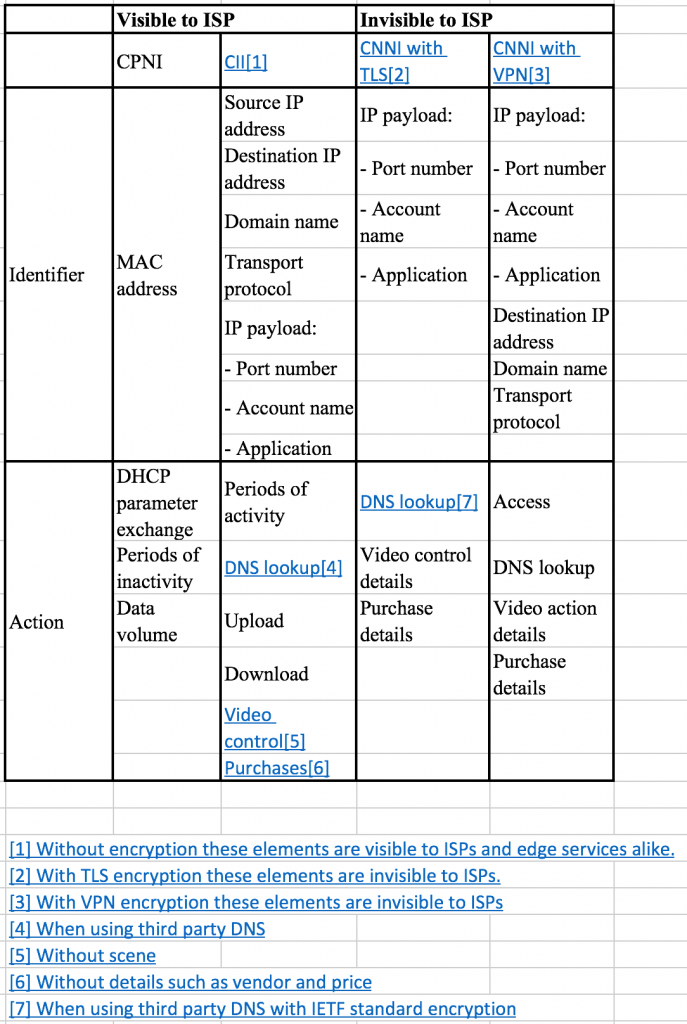

The FCC’s Privacy NPRM would gain a lot of clarity by discarding its scattershot approach in favor of a framework defined by meaningful technical distinctions. For purposes of consistency, we can segregate advertising-relevant information into three categories of visibility:

Customer Proprietary Network Information

Customer Proprietary Network Information (CPNI) is information necessary to the provision of a telecommunication service. Historically, CPNI can only be seen by networks: between a caller and a called party on the PSTN, there are no intermediaries but telecommunication networks. CPNI is said to be “made available to the carrier by the customer solely by virtue of the carrier-customer relationship.”

By its nature, information made available to other parties, such as Internet search and advertising services, cannot be CPNI because there is no “carrier-customer relationship” between the parties. Therefore, any information routinely provided to non-carrier parties by carrier customers that is also seen by telecommunication networks must not be CPNI. CPNI, in other words, implies exclusivity because it pertains to the PSTN and the design of the PSTN is centralized, exclusive, and monolithic.

Therefore, the strict definition of CPNI must include only such information as is known or knowable only by the carrier and the carrier’s customer. Two examples of strict CPNI would be 1) the Medium Access Control (MAC) address of the customer’s home router; and 2) the DHCP parameters sent by by Customer Premise Equipment (CPE) to the carrier’s DHCP server to enable the provisioning of Internet Protocol routing services by the carrier for the customer.

Additional examples of CPNI would include data on the customer’s frequency and intensity of network utilization. CPNI would not include customer location or the IP addresses of the customer’s Internet destinations because such information is known by parties other than the telecommunication provider and the customer.

The MAC address of the customer’s home router roughly corresponds to the telephone number in the PSTN regime, but the analogy is less than perfect. MAC addresses are globally unique, like telephone numbers, but they are not routable as telephone numbers are. IP addresses are fully routable, but they are not persistent as telephone numbers are. MAC addresses assigned to customer equipment other than routers do not travel outside the home and are therefore not useful for advertising purposes.

Hence, the nearest analogy to the phone number in the IP realm is the DHCP transaction that assigns an IP address to the MAC address of a home (or office) router. While there is no direct analogy to DHCP in the PSTN realm, it seems sensible to regard DHCP transactions as CPNI because they serve no purpose beyond facilitating IP routing services and are not know by parties other than networks.

Common Internet Information

Common Internet Information (CII) is information about the customer that is known or knowable by carriers as well as other Internet players such as advertising networks, websites, browsers, operating systems, and transit networks. Such information is broadly shared by Internet users with other parties explicitly and implicitly because the Internet is an open platform funded chiefly by advertising. CII is the essential input to advertising sales.

The Internet is therefore a very different marketplace than the PSTN, which is funded by subscription fees and provides users with a strong expectation of privacy. Without the sharing of such information the Internet would cease to be the open platform it is today; rather, it would become a platform for subscription-based services and for the kinds of not-for-profit activities permitted by NSFNET’s Acceptable Use Policy before the NSFNET was de-commissioned in the mid 1990s.

CII includes such information as Internet Protocol (IP) headers, unencrypted IP payloads, and Domain Name Service (DNS) queries. Unencrypted IP payloads include TCP headers and TCP payloads, which in turn include HTTP headers, commands, and payloads. HTTP, of course, reveals a great deal of information about the user that websites may either conceal or make available to ISPs, transit networks, and network analyzers.

Customer Non-Network Information

Customer Non-Network Information (CNNI) is information that can only be seen by parties other than ISPs. Such information generally consists of encrypted cookies, payloads encrypted by Transport Layer Security (TLS, AKA “HTTPS”), data streams passed through Virtual Private Networks, onion routers, or other types of secure tunnels.

Browsers, Internet applications, and operating systems have access to a great deal of information regarding the user’s interaction with data acquired or shared through network transactions. Browsers, for example, know whether users read web pages all the way to the end because they see mouse clicks and keyboard input. If a user re-reads a paragraph of text, highlights a section, or annotates a document obtained across the Internet, the browser or document reader knows these actions have taken place but the ISP doesn’t.

Similarly, if the viewer of a video program pauses, rewinds, skips, fast forwards, or replays a portion of a video stream, the video streaming service knows which scenes in the video program are the objects of these actions. The ISP and transit network can deduce that the user interrupted the program flow, but would not easily know which scenes were affected. These actions are, of course, indications of user interest that have valuable advertising consequences and therefore important privacy implications.

Types of User Information

In addition to these three categories of visibility, advertising-related privacy encompasses several types of information. The chief distinction among information types separates static information that identifies a person or device (an actor) from the activities the actor performs. Information elements in the first category are known as identifiers and information elements in the second category are known as actions or behaviors.

The Privacy Taxonomy

Conclusion

Consequently, there is no meaningful difference between the information visible to ISPs and to web services in the common, unencrypted scenario. In the new reality – in which IP payloads are encrypted by TLS or VPNs – there is an enormous difference between the small pool of information available to ISPs and the much larger pool visible to web services. But in no scenario is there any empirical support for the NPRM’s claim that ISPs are in a privileged position with respect to web information.

The NPRM’s assumption that ISPs have privileged access to web activity is not factual. ISPs have a limited view of user activity, and Identifiers that function like UIHD can be added and are added to HTTP data streams by websites as easily as they can be added by ISPs. User identification is a basic function of web cookies, IP addresses, and user account names. And unlike ISP-visible objects, web cookies function across platforms and devices. Users of a particular browser, such as Chrome, access the same cookies across desktops, laptops, tablets, and smartphones, whether connected by wired residential ISPs, business ISPs, or mobile ISPs. So the NPRM’s claim that ISPs have greater visibility and control over user web information is the polar opposite of the truth.