Cutting Through the Blog-fog on Throttlegate

FCC Commissioner Mike O’Rielly criticized Netflix’s Throttlegate in a speech to the American Action Forum Tuesday but pushed back on the idea floated by some ISPs that edge services providers should be subjected to net neutrality rules or at least investigated for deceptive practices. O’Rielly doesn’t want to compound the error of net neutrality by extending it across the Internet ecosystem, but he does believe that Netflix may have made false statements in FCC filings over the net neutrality issue that warrant investigation. He’s also concerned about the lack of disclosure to Netflix customers.

But You Can’t Throttle Yourself!

The bloggers who’ve earned distinction as Netflix cheerleaders were quick to jump to their idol’s defense with the usual mixture of misdirection, hair-splitting, and snark that we’ve come to expect from them, but they did so in a particularly unimaginative way. Techdirt’s Mike Masnick (“The Cable Industry Wants Netflix Investigated… For Throttling Itself”) and Ars Technica’s Jon Brodkin (“Netflix should be investigated for throttling itself, FCC Republican says”) mischaracterized Throttlegate as no big deal because a firm obviously can’t “throttle itself.”

Why do the tech reporting faithful ignore the effects of throttling on customers of the firm doing the throttling? It’s probably just for the clicks, but their phrasing attacks a description of Throttlegate by Wall Street Journal reporter Ryan Knutson on Twitter Friday:

Turns out @netflix has been throttling itself on AT&T and Verizon devices https://t.co/FrLElZZa7v @shaliniwsj $t $vz https://t.co/QFfRR03g6C

— Ryan Knutson (@Ryan_Knutson) March 24, 2016

Any firm that throttles its customers is “throttling itself” because throttling is restricting the rate at which data flows through its network. So the bloggers who suggest Netflix couldn’t possibly throttle its customers haven’t found the smoking gun they imagine. They haven’t exonerated the big streamer, and it’s not even close.

Why the Hostility Toward Netflix?

People who didn’t follow the Internet regulation saga as far back as 2013 are a little confused about why Throttlegate is such a big deal to the critics of net neutrality. The background is pretty simple: Netflix has a employed a “name and shame” strategy in an attempt to force ISPs to offer it more favorable interconnection terms than anyone else has enjoyed.

In June, 2013 Netflix unburdened itself to two reporters at GigaOm about an interconnection spat between its transit supplier Cogent and Verizon. The story was pretty much a non-story: Cogent obtained settlement-free peering arrangements with a number of large ISPs when it was in the actual transit business, carrying half as much traffic away from the ISPs as it terminated at the ISP networks. After signing up to terminate traffic for Netflix, Cogent asked the ISPs for more interconnection capacity and got a cold shoulder. The ISPs, chiefly Verizon, were willing to add capacity for a fee but not under the terms of the old peering agreement. So Netflix and Cogent took the issue to the media in an effort to shame Verizon into providing free interconnects.

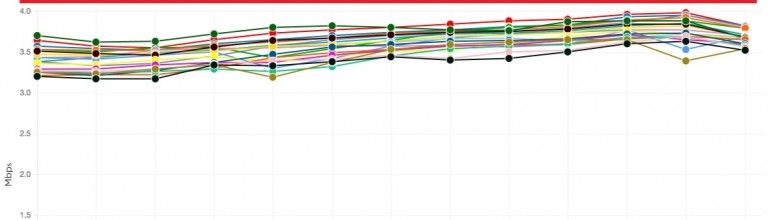

And that’s not the only time Netflix has used a “name and shame” strategy in its disputes with ISPs. For some years now, Netflix has published a monthly scorecard calculated at spurring competition among ISPs for the most favorable interconnection terms, the Netflix ISP Speed Index:

The Netflix ISP Speed Index is a measure of prime time Netflix performance on particular ISPs (internet service providers) around the globe, and not a measure of overall performance for other services/data that may travel across the specific ISP network.

The assumption behind the index is that performance is solely in the hands of the ISPs rather than a function of the design choices Netflix has made itself in combination with the ISPs’ network characteristics. This has always struck me as dishonest because the speeds the index reports are so far below the measured capacities of the networks in question that they reflect little more than Netflix’s choices. This is obviously the case where AT&T and Verizon are concerned because networks that use the same LTE technology that the big mobile players use show much higher performance figures.

Bluebird Broadband, for example, runs a fixed location LTE network with no data caps that Netflix reports running at 2.44 Mbps, four times faster than the artificial 0.6 Mbps limit Netflix imposes on AT&T and Verizon. This is not because Bluebird runs its network better than the others, it’s because Netflix has cooked the books to make it look as if they do.

While it may be reasonable for Netflix to bias the outcome of this test for Bluebird, customers who rely on this chart as good data for choosing an ISP have been misled. Would anyone choose an ISP on the basis of the Netflix ISP Speed Index? Well, they would if they believe what Netflix chief streaming and partnerships officer Greg Peters said about the Index:

This is useful information for consumers when picking an ISP, especially for those thousands of university students who are moving to Boston before school begins. When it comes to getting a great Internet connection, it is clear that a bigger ISP isn’t always a better ISP. In Boston, RCN delivers a very impressive connection, offering equal or better quality than fiber to the home.

So it’s “Trust me, I’m not your ISP.” Regardless of the wisdom of Netflix’s decision to throttle in the interest of saving their customers money, there’s no question that Netflix publishes performance claims for its own business and marketing purposes. Because of the Netflix ISP Performance Index, its throttling decisions are not simply network management practices.

Do We Care What Happens Outside the Boundaries of Net Neutrality?

The Netflix Index has been used to bolster claims of extortion against ISPs that have led to FCC investigations. In June, 2014, Netflix-friendly blogger Brad Reed reported that the FCC was looking into interconnection deals even though they aren’t “technically” covered by net neutrality:

Peering agreements between ISPs and transit companies or content providers aren’t technically net neutrality issues but they could still be potentially harmful to the open Internet depending on their terms. To bring some more light into this perpetually shady area, Federal Communications Commission Tom Wheeler said on Friday that the FCC is going to investigate peering deals that Netflix has signed with Comcast, Verizon and other carriers to determine whether the terms are fair or if ISPs are using their market power to charge content companies excessive fees in exchange for getting improved connections to their network.

So even though the behavior of ISPs at interconnection points deserved investigation despite being outside the scope of net neutrality, the Netflix throttling behavior is exempt from examination today because it’s, you guessed it, “it has nothing to do with net neutrality” according to the same critics who cheered Tom Wheeler for hauling the ISPs before to the Star Chamber. Hypocrisy is certainly one of the issues here, not just for Netflix but for their fans in the blogosphere who want to let them off the hook because “you can’t throttle yourself.”

It turns out that net neutrality is not such a useful regulatory guideline after all because it has very little to do with the way we experience Internet services. This is why technical organizations like BITAG are focusing on more meaningful terms such as Quality of Experience and Disclosure.

The BITAG Disclosure Guidelines on Disclosure

When the interconnection wars between Netflix and the ISPs were going on, BITAG wrote a report on Congestion Management that included some very specific guidelines on disclosure. This took place at an important juncture in history because Netflix was standing up its own Content Delivery Network to take middlemen like Cogent and Level3 out of the picture and because Netflix was a BITAG participant. So when we look at the guidelines it’s useful to bear in mind the fact that Netflix signed off on these conditions.

Here are the BITAG guidelines (pages 43-4):

7.1. Transparency

The BITAG suggests that ISPs and ASPs should disclose information about their user or application-based network management and congestion management practices for Internet services such that the information is readily accessible to the general public. This information should be made available on network operators’ public web sites and through other typically used communications channels, including mobile apps, contract language, or email. ISPs and ASPs may choose to use a layered notice approach, using a simple, concise disclosure that includes key details of interest to consumers complemented by a more thorough and detailed disclosure for use by more sophisticated users, application developers, and other interested parties. The detailed disclosure should include:

- descriptions of the practices;

- the purposes served by the practices;

- what types of traffic are subject to the practices, if not all traffic, and, if appropriate, a general explanation of how traffic types are identified on the network;

- the practices’ likely effects on end users’ experiences;

- the triggers that activate the use of the practices and whether those triggers are user- or application- based;

- the approximate times at which the practices are used, if they are limited to particular times of day; and

- which subset of users may be affected, if not all, e.g. the geographic boundaries in which the practices are used.

The disclosure should also include the predictable impact, if any, of a user’s other subscribed network services on the performance and capacity of that user’s broadband Internet access services during times of congestion, where applicable. These disclosures should complement ISPs’ other disclosures that describe their Internet service offerings, expected and actual access speeds, performance characteristics, and suitability for supporting particular kinds of applications.

All of these disclosures may be made without divulging competitively sensitive information and should be consistent with the requirements described in the FCC’s Open Internet Order [Open Internet Order].

[Note: ASPs above means “Application Service Providers” such as Netflix, YouTube, Hulu, et al.]

So despite the fact that Throttlegate isn’t a net neutrality violation by definition, it’s the kind of practice that should have been disclosed, should have been user-controlled, and should not have been used at the same time that the Netflix ISP Performance Index was used as fuel for stimulating FCC investigation of interconnection practices of ISPs.

It’s simply a matter of fairness and consistency, and Commissioner O’Rielly has the historical facts on his side.